HOO MOJONG: TRANQUILITY AMIDST CLAMOR

| April 21, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

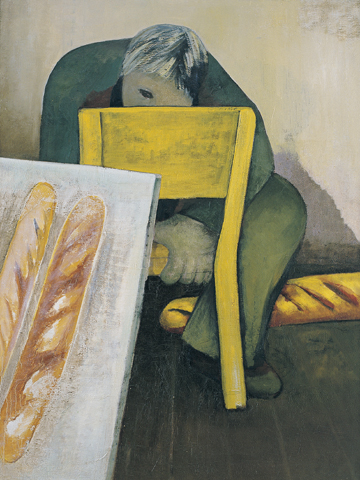

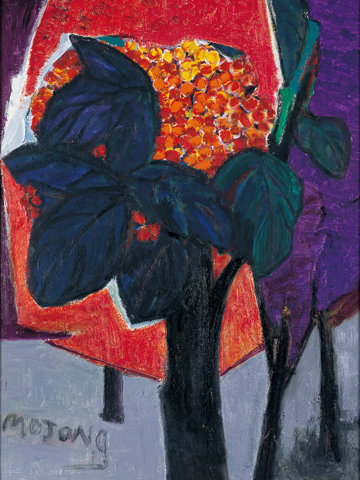

Set against the distinct uproar of modern Chinese history, Hoo Mojong’s works betray a unified, unadorned quiet. Many of her paintings are still-lifes, usually depicting everyday objects such as trees, bananas, bread, vegetables, and the like, crudely composed in rough lines. Her figures also seem cumbersome, with simplistic or omitted facial features and unusually robust bodies that might exert great difficulty and great strength could they move. Hoo’s works easily recall Impressionism and its aftermath, and with reason: she spent over three decades of her life in Paris, part of the second wave of Chinese emigré artists in Europe.

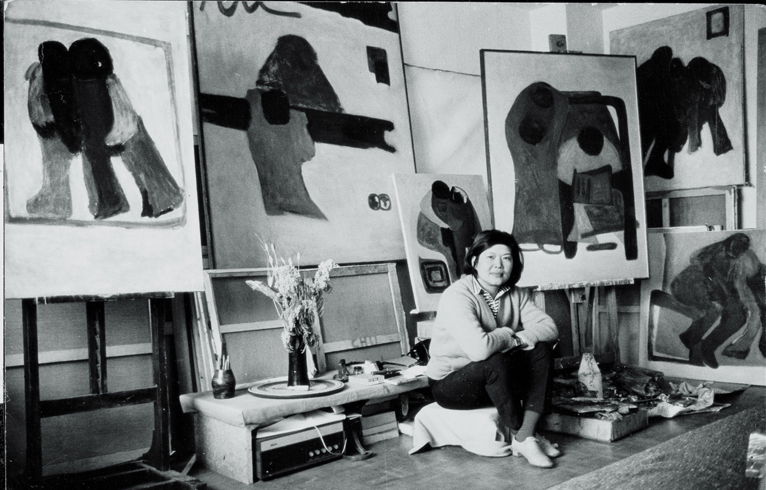

Hoo Mojong has led a colorful life, painting on the three continents she has called home. Born in Ningbo, Zhejiang province in 1924, her grandfather was a locally famous traditional Chinese medicine practitioner, her family well-to-do. She spent her childhood and adolescence in that port city, and received a good education, developing an interest in painting. During the War of Resistance against Japan, her entire family moved to Shanghai, its fortunes in shambles. To supplement family income, Hoo worked in a factory by day, attending art classes at night. She never received proper formal training; even when she was accepted into a top-tier art academy in Paris years later, she relinquished the opportunity and chose instead to hone her skill through active practice. She moved to Taipei in the late 1940s but fled to Sao Paolo in 1950, where she lived for the next decade or so. The influence of her time there is evident in work from this period. She garnered the attention of a local gallery, where she held her first solo show. Some time later, she taught a group of Brazilian students. Her works from this period are largely unaccounted for, scattered throughout Latin America.

Hoo Mojong lived in France between 1965 and 1996. Chinese artists in Paris have a long history in the twentieth century, including key figures such as Lin Fengmian, Xu Beihong, and Hiunkin Pang. Seen from the early twentyfirst century, Hoo is clearly a part of this tradition, having arrived there at a time when few from the Mainland were active abroad. In this way, she fills an important gap in the long history of Sino-European artistic exchange. Some even consider her the successor to Pan Yuliang (1899-1977) as the most prominent overseas Chinese female painter.

Hoo’s time in Paris coincided with dramatic transformations in Western art, and yet through it all her style remained more or less constant, her works characteristically tranquil. In 1968, Hoo’s “Toy” paintings showed as part of the Salon for Female Painters, winning a major award and setting her up for other exhibitions throughout Europe. The “Toy” series lasted nearly a decade, becoming her signature work. In 1970, the French Ministry of Culture granted Hoo a studio of her own to create large-scale paintings. The “Still Life” series was created during this time. This studio also became her residence and she spent most of her time in Paris there. Life in Paris was not easy. Oil paintings were difficult to sell and prints were much more marketable. In order to earn a living, Hoo learned printmaking. Her new skill helped improve her living circumstances and ultimately influenced her painting.

In the 1980s, China opened up and Hoo Mojong received an official invitation to visit. In the mid-1990s, Shen Roujian, chair of the Shanghai Artists Association, saw Hoo’s paintings in Paris and invited her to hold an exhibition in China. In 1996, the “Hoo Mojong Works Exhibition” was held at Shanghai Art Museum. Soon after, Hoo began splitting her time between Paris and Shanghai. In 2002, Shanghai Art Museum held another major solo show for Hoo Mojong. Upon completion of the show, Hoo donated the sixty oil paintings, prints, and sketches to the museum’s permanent collection. This was also the year she relocated to Shanghai full-time. In 2007, Hoo held a solo show at the National Art Museum of China, eventually donating six paintings and fourteen prints to that museum. Some of these were recently showcased in the “Five Decades of Donations” exhibtion there [see page 202]. Following the 2007 exhibition, Hoo became something of a phenomenon among Mainland collectors, as her works began appearing at auction.

From February 17 to March 6, 2011, the Shanghai Art Museum held its third Hoo Mojong solo show, showing nearly 150 representative oil paintings, prints, drawings, and sketches from the 1950s to recent times, perhaps her most comprehensive retrospective to date. At 87, Hoo is still going strong, experimenting with new styles and making new works.