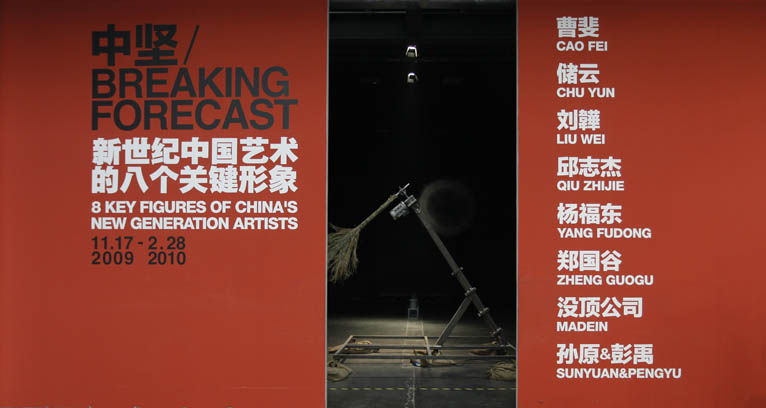

BREAKING FORECAST: 8 KEY FIGURES OF CHINA’S NEW GENERATION ARTISTS

| February 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 1

“Who are the next generation of artists in China?” This is the question the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art’s (UCCA) second anniversary exhibition “Breaking Forecast” aims to answer. But in attempting to establish a contemporary history, the show raises an equally important question: Who is qualified to name a generation?

Eight artists are named as the “key figures” of the new generation, and are used to preview the latest and future trends coming out of China. It is confusing to many long-term observers because these artists aren’t exactly new, and some aren’t even considered young by local standards. (Qiu Zhijie, for example, has been active since the early 1990s and already enjoys an established reputation as artist, critic, curator and educator.) Wondering then who identified the trends here as “emerging,” it seems less as if curatorial duo JeÅLro^me Sans and Guo Xiaoyan did not reach value-based decisions through thoughtful deliberation, but more as though a handful of Chinese galleries influential in the international art circuit exerted their considerable clout. (Widespread rumors of early requests to these galleries for production fee support only add to this feeling.) In this sense, UCCA’s role—perhaps not entirely inconsistent with Sans’s vision—is more that of an art aggregator, and this show a highlight reel of recent works intended for a broader audience than usual.

From this prognosis, what conclusions might we draw about the “new generation?” For starters, Chinese artists have a wry sense of humor and an affinity for the ready-made. They completely reject painting as an act of self-expression and shirk personal narratives (with Cao Fei’s Second Life project as an exception) in favor of clever or socially provocative acts that challenge social mores. They aren’t apolitical but might be despondent, and although a subtler vocabulary of “Chinese characteristics” has emerged, the choice to identify with cultural background is clearly optional: Xu Zhen (now working under the pseudonym “MadeIn”) recently mocked the very idea of stereotyping cultural identities by staging a fictional “group show” of Middle Eastern artists full of the same clicheÅLs that marked the “China shows” of an earlier era. All in all, art from China looks globally astute yet emotionally detached.At its best it inspires new ways of seeing; at its worst, it manufactures elaborate spectacles.

In the exhibition entrance, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s stunning A Moment of Clarity (2009) is the materialization of an idea. At the far end of the nave, a contraption emits a large smoke ring that silently careens down the blackened corridor only to be destroyed by a timed whiskbroom turning on a motorized spring. The broom reaches like a hand into the air and dissipates the ring before it has time to degenerate of its own accord. This work’s beauty and success lie in its raw form, its coarse simplicity and the metaphorical possibilities it allows the viewer.

In an adjacent room Chu Yun’s Constellation (2006/2009) is an utterly dark space buzzing with a low, electrified hum. Inside, red, blue and green lights blinking at different rhythms give the sensation of a space with indefinite dimensions, an effect created by midsized kitchen and office appliances arranged over tables of various heights. It is at once a sculpture in its own right and a recreation of a crowded living space inspired by the artist’s time in Shenzhen. Devoid of politics, culturally universal and pregnant with possibilities, both these works are straightforward, presenting the audience with formulas to decipher.

While works by Liu Wei and MadeIn (Xu Zhen) share a register of political insinuation and veiled social commentary, both also reflect a production process that mimics business models. Ever the artist as entrepreneur, Xu Zhen established his “multi-functional” company in 2009, the latest in a string of ventures that has included an art website and a spoof gallery. Likewise, Liu Wei’s formulaic creations are obviously made with the help of a production crew of semi-skilled workers who help him realize paintings like the anonymous fluorescent landscape ZJ30033402 (2009) and his sculptural cities of rawhide.

MadeIn shows Calm (2009), a pile of red brick debris spread over a waterbed that comes from the aforementioned “Seeing One’s Own Eyes—Middle East Contemporary Art Exhibition” with which the company began back in September. Calm recreates the dizzying effect of desert sun, or perhaps mimics the aftermath of a suicide explosion or forced demolition—unfortunately, aside from being installed in a remote corner of the exhibition, the piece loses something once removed from its original context. Likewise, the early Xu Zhen piece In Just the Blink of an Eye (2005/2009) is thwarted by this installation, its visual artifice sacrificed as live performers, who should appear frozen in gravity-defying positions, are seen getting situated into their contraptions. The viewer is suddenly privy to the performers chatting with each other, and to the metal supports that peek through their clothes.

Cao Fei’s mesmerizing virtual animation The Birth of RMB City (2009) is screened inside a mountain whose surface appears digitally rendered, while her Second Life avatar “China Tracy” can be seen on several tiny screens with headphones. Pigeonholed as the “pop culture” artist, Cao’s incarnation of RMB City offers a few quiet moments of escapism, as possibilities of a utopian, alternative future are dangled before us like the image of the CCTV tower hanging off a crane in her virtual skyline. The entire RMB City project speaks loudest to a younger generation and to Second Life enthusiasts.

Qiu Zhijie’s work, an enormous allegorical “ink fountain,” stands in sour contrast to its Disney-esque neighbor. Vertical train tracks reach to the sky and thick black liquid cascades into a golden pool below, the overwrought drama somehow highlighting his incongruous inclusion in this exhibition of “young” artists. Zheng Guogu’s Sense of Empire (2009) is an attempt to relocate this utopia-in-progress from his hometown of Yangjiang to the gallery space. (Zheng’s fantasia on the city outskirts is a walled cluster of buildings whose architectural forms are based on motifs from the computer game “Age of Empires.”) The attempt fizzles in this context despite the considerable merits of the project itself.

“Breaking Forecast” offers a glimpse at some impressive monumental works, and perhaps even a few monumental failures, but is far from an integral picture of “China’s New Generation Artists.” The attempt to bring many great artists together seems valiant at first, but as for predicting art movements to come, parties with obvious investments in the “future” shouldn’t be responsible for writing history. Lee Ambrozy