YIN XIUZHEN: SECOND SKIN

| June 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 3

Upon entering Yin Xiuzhen’s show “Second Skin” at Pace Beijing, the first thing one could smell was the scent of a woman, a scent borne by all variety of clothing. Textiles have been a persistent element in Yin’s artwork and can be traced back to 1995 and her “Suitcase” series. The textiles she used back then were old clothing that she had once worn; displayed at this show was recent installation work mainly composed of old clothing. We might say that old clothing has become a bridge for Yin, linking her life experiences to her work.

The use of textiles is often taken as a differentiating symbol of the female artist, and the feminine qualities of Yin Xiuzhen’s work are undeniable, particularly this time around; not only did Yin make use of old clothing, some of which bore the feminine markers of lace, pleats and buckles, she also used feminized cosmetic products such as rouge, powder and sponges as well as feminine colors such as crimson and teal. But in this show, the perception of Yin’s feminine qualities arose not from these symbols, but from a certain female expressive model transmitted by the use of old clothing.

Clothing and women have always been tangled together, linked ever since the ancient social structures based on men plowing the fields and women weaving. However, the ideological attachment of clothing as semantic system and cultural symbol to the female sex began only with modern society. This is related to the process by which women became an “other” to be “gazed” at—the commercialization of the female body in consumer society.

The concept of the sexualized “gaze” was first raised by film researcher Laura Mulvey in her article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in which she used a politicized form of psychoanalysis to reveal the patriarchal unconscious of the cinema. Mulvey pointed to the gender consciousness of looking, e.g. the sexualized gaze. By gazing at women, men consume their bodies, and women are objectified in this process of “being looked at.” In the male vision women are constructed as a kind of object of exhibition, and clothes are the most direct prop for women’s constructed identity. This idea was expressed particularly clearly in Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980); fascinated with dress, Sherman used clothing to decode or confuse her identity, and through the identity drift this created, engaged in silent parody and resistance.

This interest in clothing brings the modern Chinese writer Eileen Chang, who is said to have had a “clothing fetish,” to mind. In the space of Chang’s fiction, women as passive objects become the subject of the stories’ fetishism, using clothing to bring about “earnest and trivial disturbance, sincere and purposeless battle.” Chang used the feminine semantic model of clothing as a metaphor, and this model was internalized in the sensory experience of the urban woman, a bleak and powerless current accompanying women’s migration to the margins of modernity. This sensory treatment of women’s internal and external conflicts is made concrete in Yin Xiuzhen’s artistic practice of using old clothing for materials.

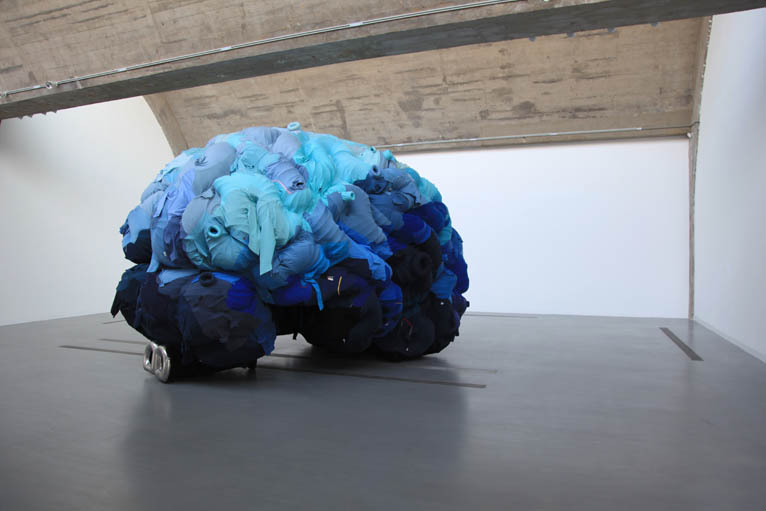

The clothes one could see at “Second Skin” were no longer worn on the body but taken off and turned into nearly twenty sculptures and wall pieces. The lace, pleats and sequins on the cloth, those intimate pink and teal colors, were enough to convince one that these once intact pieces of clothing bundled women inside them. While some articles may have been worn by men, the daily life and experience to which they spoke were very much feminized, a semantic model for history, memory, desire and illusion, much like the clothing Chang used. The logos that appear unexpectedly in the work make us realize that this is an urban living space; while this is merely a feature brought along by the material used in the work, we can understand it as carrying feminized perceptive connotations.

Compared to her previous works Collective Subconscious (2007) and Introspective Cavity (2008), Yin Xiuzhen’s feminine semantic model as expressed in this exhibition was purer and more concentrated. As an artist who traffics in daily articles, Yin has, besides fabric, also used materials such as steel and concrete, often stressing strong conflict between the semantic symbols of the different materials. Examples of this include the weapons wrapped in cloth in Fashion Terrorism (2004) and Clothes Airplane (2001). While the conflict in these works is intense, on one level this can be understood as a conflict between the feminine perspective and the external world. In this exhibition, Yin’s work on the one hand purified this female semantic model, and on the other transformed the conflict created by the collision of external forms into a relatively peaceful internal struggle. She has carried out a certain internal conversion and revision of the female semantic model, taking her abstract “paintings” (or sculptures) made of crimson, green and blue old clothing, putting powder on a sponge to form her abstract painting effect and wrapping old clothing into “books” and placing them on a shelf, the other side of which is in fact a wardrobe. These pieces used a more moderate and natural method, concentrating on the process of use and reconstruction of the daily material of “clothing” in a latent “masculinized” method, conveying a sense of “masculinized” rational power that permeates, rather than conflicts with, the work.

A collar with cement poured on it, a sharp wave-shaped knife blade, a cold highway, a bookshelf representing knowledge and reason, a simple abstract plane… in modern society these elements are linked to male-centered rationalism, a link that can be understood as a kind of intrinsic reasoning rather than external violent forms. Using these elements to address clothing filled with feminine purpose presents a kind of hermaphroditic stalemate and tension in Yin Xiuzhen’s work, which in turn allows it to shake off the passivity and ambiguity of the Chang-esque “earnest and trivial disturbance, sincere and purposeless battle” feminine semantic model. One senses a subject that penetrates women’s daily experience to enter the male world. This sensibility simultaneously contains distinctly feminine characteristics and debunks the identity demarcations of gender essentialism. This migration of meaning blurs those innate identity prejudices. The kind of “double language purification” Yin exhibited in this show allows her work to achieve a clearer and more powerful step forward, possibly taking her art into freer territory. Li Xiaonan