PAN GONGKAI CONCEPTUAL ART EXHIBITION

| August 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 4

The casual visitor to the CAFA Art Museum late this spring would have noticed a giant nine-by-nine meter ink painting hanging in the atrium of the still novel Arata Isozaki building, in telling contrast to the characters of the CAFA moniker as written by Mao Zedong. The painting belonged to CAFA director Pan Gongkai, some wilting lotus flowers in the inky expressionist style of his father Pan Tianshou, expanded to scissor-lift scale. In a way, this single painting could be taken as a metaphor for China’s developmental and aesthetic condition: self-consciously expansive, nodding simultaneously to Western form and Eastern content, not immediately beautiful, and tied up in the Oedipal dramas of both family and state.

This was the opening salvo in “Displacement • Flashes of Thought: Traversing Duchamp,” otherwise known as the “Pan Gongkai Conceptual Art Exhibition.” The former is a Chinese title par excellence with the round suspended dot denoting an equivalence between the words on its either side, which are not easily translated. The subtitle “Traversing Duchamp” is one character off from “transcending” Duchamp. More interesting though is the notion of a title that so explicitly denotes the work at hand as “conceptual,” a gesture that seems to externalize and exoticize the forms Pan employs in what is to be taken as a rare departure from ink painting, and a demonstration of what the director of the nation’s top art school might mean by “contemporary art with Chinese characteristics.”

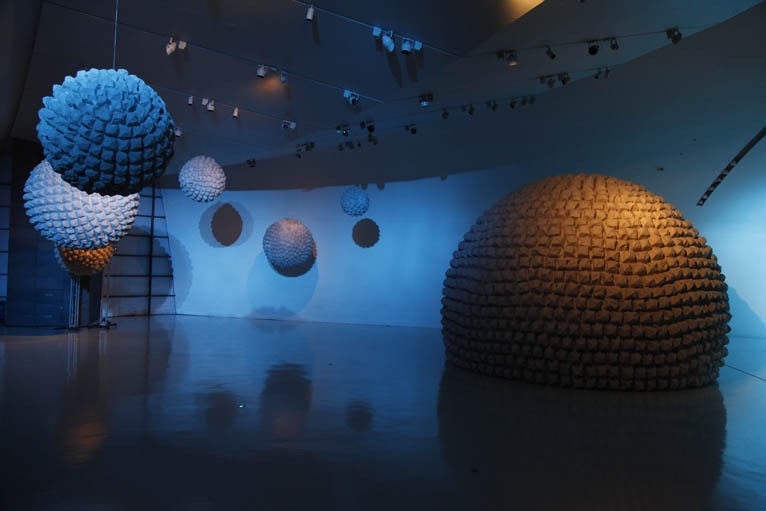

Upstairs, past a mezzanine of crumbling architectural models for the World Expo China Pavilion on whose design team Pan Gongkai sat, one enters the main room, a fantasia of hanging piñata planets in xuan paper, spheres that resemble nothing so much as giant lychees. The central lychee is kitted out as a space capsule containing Pan’s working environment. Through tiny portholes, we see his desk stacked with a pencil cup, a bottle of Nongfu Spring mineral water, a stapler, an issue of the campus paper. We see his office chair, and slung over it his sports coat. On the back of the flying egg, tiny windows contain more of his everyday items frozen in Lucite: a cell phone, notes from colleagues, eyeglasses, paperclips, heart medications. It is ego sublimation of the most revealing variety: one imagines Pan imagining himself as ink-and-wash cosmonaut, hovering above the CAFA campus and the Chinese art-education system in a metaphysical space of his own design. If this were not clear from the work itself, the next room contains a series of didactic “making of” photo collages, full of snapshots of the leader-visits-village variety.

The museum’s top floor is home to a work no less fantastic. The results of Pan Gongkai’s ongoing research project “The Road of Chinese Modern Art” unfold in a labyrinthine series of text panels advancing arguments like, “Traditionalism, Syncretism, Westernism, and Massificationism are projects of self-conscious choice in Chinese modern art.” Pan’s “Road” recapitulates the emergence of a distinctly Chinese contemporary sensibility as the endpoint of the twentieth-century catch-up drama. The dialectic with the West, and the distinctly constructive role played by “massificationism” (by which he means the revolutionary realism of high Maoism) are enshrined in what looks and feels like an art-specific instance of party historiography. If it seems marginalized up in the museum attic, remember that international luminaries including Slavoj Zizek were bussed here in May for a special viewing during the second “China International Art Forum.” Presumably, at least some of them took these tired formulations as indicative of the general state of the Chinese discourse.

Of course our parents’ deepest questions are our own starting points, and our thrills, in turn, are our children’s mundanities. Ask anyone who has ever seen a toddler play with an iPhone. And yet the question of East-West transfer seems to cling on well beyond its date of expiry, its perniciousness exacerbated by a decentralized information culture where people only get what they see, and only see what they want. One can only hope that the students of CAFA understand this intuitively, lest they find themselves caught in an essentialist conversation that, like the encapsulated heart medications, has long passed its expiry date. Adam Gellin