GUANGDONG: THE RISE AND FALL OF A REGIONAL FANTASY

| October 2, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

The contemporary art world’s concept of the “Guangdong artist”—emerging from the haze of the growing Pearl River Delta cities of the mid-1990s, flourishing through the first years of the new century, and fading as the entire ecology of the art world grew, enticing many of those with whom the designation was initially associated to move north toward the end of the last decade—is almost far enough behind us to allow for some preliminary historical reflection. Like most things, it was a coinage deeply related to a national situation. “Guangdong artists,” known more for interventions in the city than for any relation to an immanent regional culture, were most aptly suited to a major shift in the discourse around art here, from political symbolism to urban anthropology. In the process, this place-bound peg helped to chip away at the monolithic understanding of “Chinese contemporary art” then in circulation internationally.

Certainly the region, which initially, for art purposes, centered on Guangzhou, is not without its own avant-garde history. A recent film from the Asia Art Archive From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng, charts the early years of the Cantonese awakening brilliantly, incorporating interviews with major figures like critic Li Zhengtian and artist Wang Du, whose Southern Art Salon offered some of the most savvy performance work to come out of the ’85 New Wave. The film argues that the region’s more open access to objects and ideas coming in from a still-colonial Hong Kong combined with a national craze for thinking to form a particularly striking strain of conceptualism. The early nineties, marked nationally by a deepening of economic reforms that centered on Deng Xiaoping’s trip to Guangdong, saw events like Lu Peng’s famed “Guangzhou Art Biennial (Oil Painting Division),” a periodic exhibition as art fair that looked for a market which didn’t quite yet exist.

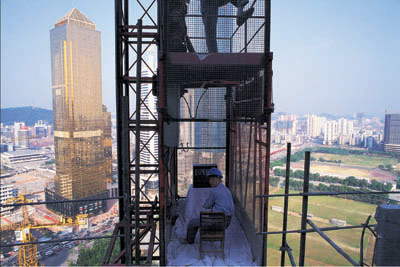

It was from this mix that the Big-Tail Elephant Group emerged, the preface to their first exhibition in 1991 clearly stating a connection to the regional situation: “Out of the motley disorder of this transitional period, we are trying to find a way to make our ideas clear, not some beginning of thinking, but a way out of the sediment.” This free-form collective of Chen Shaoxiong, Lin Yilin, Liang Juhui, and shortly later, Xu Tan mounted major exhibitions again in 1992, 1994, 1995, and 1996 and has never formally dissolved. The group, with its highly earnest urban guerrilla interventions in the streets of Guangzhou, gained some renown on an international scene that was, at its more curatorial fringes at least, starting to look beyond the big-head painting with which it was essentially coterminous. In the strain of to-the-streets actionism of pieces like Lin Yilin’s famous Safely Crossing Linhe Road or Liang Juhui’s hour-long performance of playing video games in a worker’s elevator, they produced moments in the city that were poetic in a way that transcended place.

Indeed, just as this early wave of indigenous exhibitionmaking ended, another wave of Western discourse-making began in the form of Rem Koolhaas’s research into the Pearl River Delta. That project, begun under the auspices of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Project on the City, exhibited at Catherine David’s 1997 Documenta X, and consolidated in a 2001 book entitled The Great Leap Forward, was how the majority of international observers came to encounter the region. Through a massive exercise in data and image collection, Koolhaas painted a compelling picture of a land where skyscrapers were built before they were designed, where twenty-five year old architects had entire districts to plan. Coming at the high-tide of a globally articulated convergence of architecture and cultural theory around the journal ANY (Architecture New York) and its itinerant yearly conferences, Koolhaas’s PRD research became a sort of stand-in for the urban anxieties of an entire moment.

How this translated into the art world was a slightly different story, and one that hinges, in large part, on the PRD’s favorite curatorial son, Hou Hanru. Hou, the youngest member of the crew of curators behind the 1989 China/Avant-Garde exhibition, had been living in Paris since shortly after that show, where he had fallen in with an international circle that included Chinese artists like Huang Yong Ping and, notably, the young Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. Hou and Obrist organized, famously, the 1996 and ongoing exhibition “Cities on the Move,” which centered on works about emerging urban conditions, and in which artists like the Elephants and their sometimes-collaborator Zheng Guogu played a major role. Hou Hanru quickly came to the idea that there was in fact something distinct about the situation in his hometown and its environs, something which made it, in the words of the title of the 2005 Guangzhou Triennial which would mark in a sense the end of the line he was about to begin, a “special laboratory for modernity.” This formulation had the backing of history: Sun Yat-Sen, godfather of the revolution, had come from here, after all, and a distinct language and culture had kept the region always somewhat separate from its northern neighbors. Hou came up with a catchy phrase that seemed to encapsulate this entire condition, calling it, “Canton Express,” and incorporating it first into the Gwangju Biennale he curated in Korea in 2002, and then at the Venice Biennale the following year. Through his special relationships with the artists of the Big-Tail Elephant generation, but also younger players such as Ou Ning and Cao Fei, then best known for their pioneering documentary Sanyuanli, Hou managed to eke out a sprawling perch on the global scene for his idea of a Cantonese subjectivity.

sssssssss

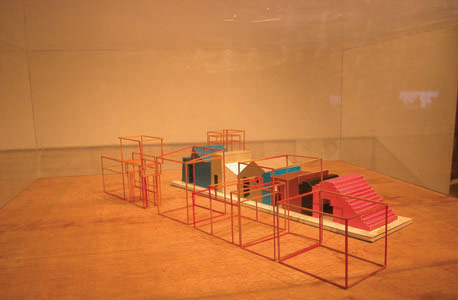

The development of the local system aided in this emergence, or perception thereof. Chen Tong and his bookstore-cumgallery Borges Libreria played a major role in providing artists with a gathering place throughout the late 1990s. Alongside the heralded First Guangzhou Triennial in 2002, Vitamin Creative Space opened its first exhibition above a vegetable market in the city’s Chigang section. What began as a humble alternative space emerged into an internationally regarded gallery, welcomed at major art fairs and linked to taste-making collectors and curators, and boasting a stable of artists that seemed, collectively, to stand for something, even if no one was quite sure what. Ou Ning’s 2005 showcase of the creative classes “Get It Louder,” currently in its third edition and under the direction of LEAP’s corporate parent Modern Media, continued to push for the idea of new things coming from the south.

And then, just as suddenly as a new skyscraper goes up in Shenzhen, the Cantonese artist craze subsided. In the early boom years, circa 2006-08, it was a cliché to note that the southern artists were moving north, a trend exemplified by Chen Shaoxiong and Cao Fei as well as “Shenzhen artists” including Jiang Zhi, Chu Yun, and Liu Chuang. For a few years, even the inveterate Cantonese artist Zheng Guogu, who heads a roving band of calligraphers in his native Yangjiang where he hosts visitors from around the world, seemed to be spending a lot of time in the capital. The passing of Liang Juhui, in 2006, almost marked the end of an era. But the real culprit was less these specific developments than a larger sense that being identified with a specific region no longer offered any distinct advantages beyond a group of people with whom to share stories and a common dialect. Where once it had seemed innovative, even subversive to be associated with a region instead of an entire nation, by the end of the bubble, the only identity an artist needed was his or her own name.