MATT HOPE: MAKING THINGS WORK

| October 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

Matt Hope has spent the last three years deep within the recesses of a studio and gallery compound on the south side of Caochangdi, putting off his debut solo exhibition. Instead of rushing into the public eye, he has used this time to explore the processes and infrastructures of fabrication throughout Mainland China. Hope knows his fabricators well: from the machine tooling plants which make his custom screws to the granite quarries which attempt to cut him perfect stone cubes, his practice draws heavily on the ability of factories to work to his exacting specifications. While an ever growing list of American artists have commissioned agents to fabricate computer-designed installation components, taking advantage of China’s competitive prices and turnaround times, Hope has indulged in the interpersonal intricacies of these possibilities, pioneering a fetishism of process that could rival that of post-industrial form itself.

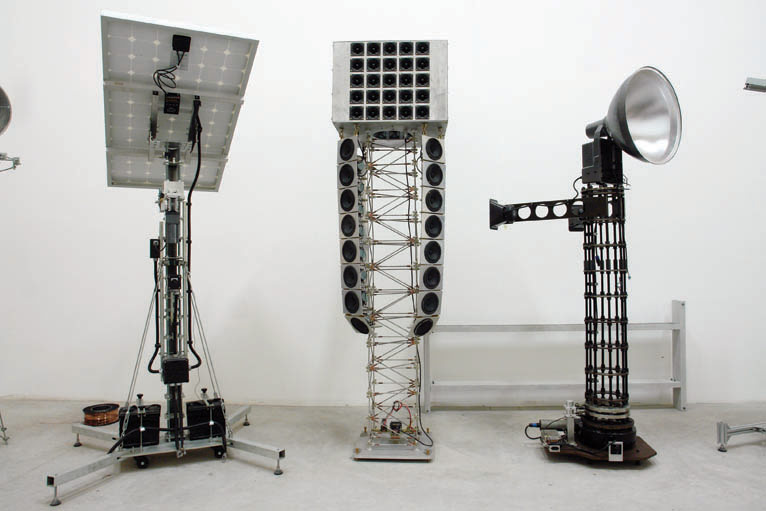

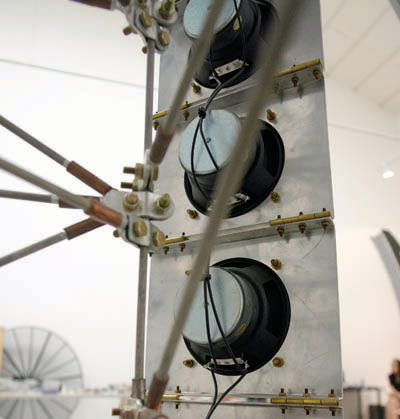

Chief among these recent projects is the series “Towers” (all works 2009-2010), which consists of ten mechanical objects, all just beyond the human scale at two and three meters high. These works extend the logic of sculpture through engagement with a Modernist ideal of industrial formalism that, here, appears pitifully useless and yet ultimately transfixing. Many works in the series subvert the connection to infrastructural matrices from which they have materially emerged, as with Tower 1, which emits sound from a mounted black speaker only after it is disconnected from the electric main; Tower 4, which transforms fluctuations in the National Power Grid into an audio signal broadcast through a menacing cubic array of speaker cones; and Tower 8, which uses the corona effect to collect airborne particles in a mechanical lung before pressing them into solid shapes. Others are more self-defeating, as with Tower 6, which consists of a solar-powered solid state condenser that accumulates atmospheric water in a small reservoir until the moisture short-circuits the system; Tower 9, comprised of two industrial solenoids that pull against one another, activated by an acoustic lighting sensor rendered virtually useless through connection to a loudspeaker; and Tower 10, which generates and focuses an acoustic signal through 260 speakers, but only after a beam is broken through the movement of the head.

Most striking of all with regard to the “Towers” series is the construction of these uncanny and often disconcerting reconfigurations of the relationship between man as artist or producer, man as viewer or user, and machine. The vast majority are built from steel, aluminum, cheap industrial shelving, stock electrical components, and slightly more exotic electro-acoustic parts, all available in the electronics markets Hope combs on a regular basis. But in many cases, the artist has chosen to fabricate electrical and structural linking elements to custom specifications with his manufacturing partners in order to link two existing components never intended to work together; these pieces thus become hybrid efforts of relational production difficult to reproduce without both flexible tooling facilities and a willingness to place these components in highly unorthodox situations. Moreover, because this project has unfolded across a span of some two years, the uses, functions, and abilities of many of the towers have undergone enormous changes, making redundant or irrelevant a certain set of these custom components once intended to link two standard pieces of hardware.

That these discarded odds and ends sit alongside the “Towers” themselves in the studio environment should come as no surprise in terms of either aesthetics or method of production. The sculptural logic of the “Towers” series in particular is that of assembly and configuration, lying in the act of drawing together a wide range of structural and relational possibilities in order to build a mechanical object that speaks in an almost human tone, gesturing through its audible squeals and groans towards a cynical but rather humorous take on the unique conditional formations and, more importantly, failures of the machine in a post-industrial era that has not yet fully reached the region in which they were produced. The discarded components are naturally much simpler in terms of execution, even to the point of minimalism. Although they were never intended as sculpture in a rigorous sense, these forms nevertheless emerge from the same systems of production as the larger projects of which they were once a part; now isolated, they pose fascinating questions about the status of absence and empty space within the sculpture as an assemblage—albeit one that cuts ties with appropriation and the readymade as core elements of the process of spatial realization.

This idea is again echoed in the second series “Tools” (all works 2009-2010), which in many ways absorbs the minimal forms of the discarded components and expands their logic of the piecemeal and the liminal into the practice of objectbased sculpture. Broadly speaking, these pieces reconstitute the paradigmatic shapes of familiar tools, fabricating the forms of objects bearing a strong sense of resemblance to the category that generated them but, to a greater or lesser degree, deprived of their use-value. Rather than purchasing his tools at the local hardware markets, Matt Hope designs and produces them. He has made, for example, a sledgehammer and a pickaxe, both of which could be coerced into performing their assigned functions even if they do reveal something of the sheen of a sacred object, imbued in form rather than function with the totemic spiritual value of the machine that also appears in the “Towers.” There are also a number of more complex installations of moving parts—a ladder, a cargo dolly, a wheelbarrow. These objects seem to attest to the sheer joy of being able to control in minute detail every facet of artistic production, right down to the bolts and other fasteners that make up the basic tools of the studio process. But on another level, it also calls upon the anxiety of absence that appears with the discarded components left aside through such methods, drawing on formal resemblance to reappraise the value of functional intentionality.

As the mechanical sinew holding together both mechanical assemblages and very human networks of production and consumption, these unneeded fragments of sculpture speak on behalf of concepts that, now discarded, once held widespread currency. In his expansive body of work to date, much of which has yet to be exhibited in a formal context, Matt Hope presents an alternative reading of commonplace ideas that now appear trite: China as the factory of the world, a country in which human labor remains more cost-effective than technological innovation. Revisiting at a much finer scale the questions that contribute to such superficial understandings, these sculptural objects and their steely afterbirth pursue the assessment of form against the broader systems that co-produce the field of assemblage.