THE SKY ABOVE

| October 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

“When an established artist reaches middle age, what sort of work should he or she create?” This is a question that many of us face today. It concerns us, when we consider an artwork, and it concerns the artist, in how he or she should assess their own creation. Whether or not we like to admit it, art—in terms of production, consumption, creation and critique—has turned into a young man’s game, constantly seeking out the new and fresh. In China, contemporary art seemingly lives out a strange existence: the moment it is born, it is already old, but at the moment of death, it still hasn’t grown up. Acceleration in artistic production and consumption cannot eradicate artists’ anxiety, no matter how indifferent they may seem on the outside.

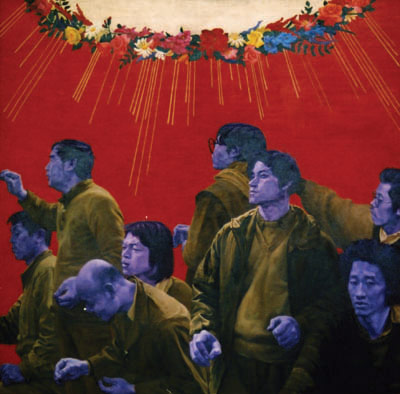

It was this question that lingered in my mind as I visited Yu Hong’s exhibition “Golden Sky” at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art. These days, people may have already forgotten the “New Generation” movement to which Yu is often assigned, remembering only a few of that crew’s more successful members. The “New Generation” arose nearly twenty years ago when a few artists, freshly graduated from their realist educations and following the avant-garde movement and the brief but severe instability of the late 1980s, began to depict the monumental absurdity of everyday life. Within both the academic realist tradition and the conceptual avant-garde which reacted, these depictions of ordinary moments were considered “vulgar” even before they appeared on canvas. The New Generation artists responded by working from everyday photos, employing the cinematic language of the narrative lens in their painting. Likewise, fashion was an element, as Yu Hong would use bright colors to level out the background of her canvases. In Golden Sky she also used this technique, as evidenced by the magnificent and dazzling golden background that is this cycle’s distinguishing characteristic. In the super-developed visual culture of today, using gold assumes the risk of poor taste, as the contextual relation to yesteryear has been lost. Gold is a sincere color with its own special cultural history, but this history has today been transformed into a negative of itself. The awkwardness of this situation is touched on in the opening of this article. Here we are not talking about an isolated anxiety, but rather the shared anxiety of our age. Speaking more precisely, this anxiety spans across the heart of all painters, of all realistic painters.

Beginning in the 1990s, Yu Hong’s work grew thematically stable. Her painterly antennae would feel out towards her close friends, family, and her own body. She scrupulously guarded her duties, using the relation between herself and her surroundings to define her body. Obviously, she was unlike those artists who found their subject matter in the radical changes of world around them, those who could effortlessly adjust to these unpredictable conclusions. Her Positivistic attitude is what makes her work most captivating, what makes her work especially precious amongst all the rest of the hubbub. Each and every one of her figures is a culmination of her experiences, the joint consideration of herself and her depiction of others. Careful analysis reveals that behind those exaggerated and vivid forms, there lies a force of reason that goes beyond any distinctly female melancholy. However, considering how quickly art is now produced and disseminated, this force of reason, which best suits a contemplative gaze, can be very easily drowned out. People are swept toward progress by the tide of the times. Even as she has stayed true to stable schematics and cold rationality, Yu Hong has, in recent years, constantly moved from painting to media like silk and silicon, perhaps to keep up. In this body of work, in a restrained and polite manner, she is attempting to remind people to gaze back upon that force of reason.

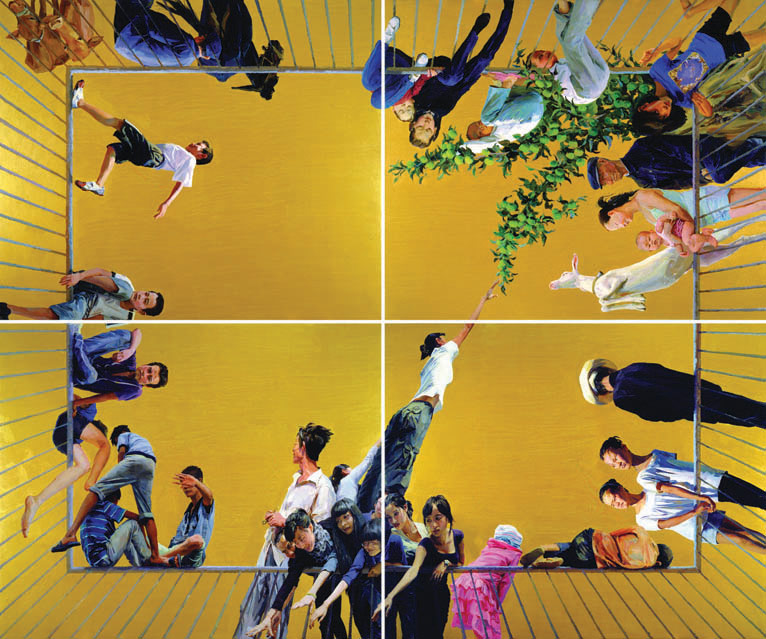

From this perspective, the four paintings that make up Golden Sky can be seen as a cultured attempt at suspension and cessation. On the one hand, Yu Hong employs “stylized” language. In the manner of religious ceiling paintings, she brings people from everyday life and current events together, and conforms them to religious implications of thousands of years. This stylization is absolutely not simplification. It is a refinement of the force of reason, or a moment of doubt, which has consistently informed her vision. On the other hand, as the little room left for art in real life is relegated to the walls and floors of museums and novelty is no longer a possibility, Yu Hong has taken to religious motif, and suspended her own artwork in the untouchable sky. This lofty stance has always been Yu Hong’s internal disposition; only this time has it been resolute enough to clearly emerge as the work’s spatial presence.

For this lover of painting, the chance to hang in midair has become a source of unlimited delight. On the floor of her cramped studio, she researched the technicalities of looking up at the sky. She experimented with how to overcome the canvas with stroke, how to give flight to the heavy human body of reality. In this process, she herself achieved a sort of flight. Unlike the great ceilings that dot classical art history, Golden Sky does not imagine the Kingdom of Heaven, but tries to elevate our world, so prosperous yet deficient, towards becoming the Kingdom of Heaven. From up above, it casts doubt back upon ourselves. These four paintings were not created in the air, but on the ground. This seems an apt metaphor for her entire approach.

When these depictions of reality appear in the golden sky, our own reality comes smashing to the ground. Be it through simple painting techniques or the clarity of the language of space, Yu Hong has used the most concise manner possible to surpass the noisy clamor of reality, as well as the very language of art, and hide herself in golden color. If we understand Yu Hong’s twenty-year creative journey in the face of that noisy clamor of reality, we will definitely feel the language of space as it flies in the sky. Hers is not a “great performance,” but rather a “great refusal.” She has refused reality and the handshake it expects of her, instead choosing transcendence. And that which is transcended also includes the expectations of her self. But no flight lasts forever. We remain on the ground, eager to see Yu Hong again after she comes back down.