A GNASHING OF THE TEETH: THE ART OF CHEN XIAOYUN

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

“Symbols are the only tool by which I profit from the labor of others.” – Chen Xiaoyun

“Poetic” is the word most often used to describe work by members of Hangzhou’s prolific video art community. Over time, relationships between the community’s members have changed, members have moved, and artistic differences of opinion have appeared, scattering the original membership to the four winds. But, even now, the “poetic” label still remains affixed to the group’s work. What exactly is this very generalsounding adjective referring to? We really don’t know. There are more or less two possibilities for what people might mean when they evoke the word “poetic”: the first is a kind of formal linguistic analysis, the commentator seizing on a paradigmatic relationship within the work. This relationship might arise from the work’s symbolism, props, characters, or dialogue. Or it might arise from the non-linear narrative logic formed by a series of shots once they’ve been edited. The second possibility is a kind of essentialist inertia embedded in the mind of the commentator, wedding the artists to Hangzhou’s cultural scene. Perhaps, in that moment, the critic is thinking not of the artist about whom he or she is supposedly writing, but about fitting that artist into the mold created by Yang Fudong.

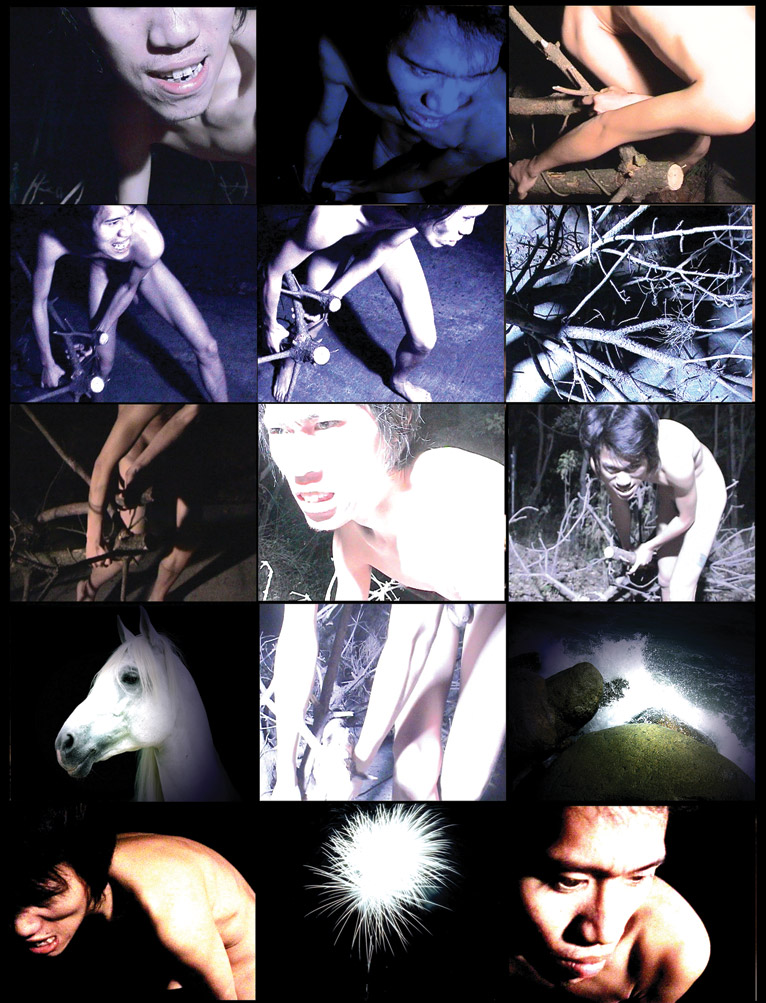

Unfortunately, the somewhat inexplicable perception of Yang Fudong’s “movies” as a reference point is something with which each the members of the Hangzhou video-art community must contend. With this in mind, it’s not hard to understand why Chen Xiaoyun, a core original member of the campaign, has such a negative opinion of his longest work to date, 2004’s Queen Lili’s Garden. Indeed, after Queen Lili’s Garden we see no more feature-length films by Chen Xiaoyun. As of late, though, his focus has not been on the length of his works, but on his insistence that they reaffirm a kind of “defect” that finds its emotional origins in realism. This insistence gives his works a certain nameless quality all their own. The visual language of these works should, along with their obvious awareness of their own limits, be enough to thoroughly put to rest the coarse nostalgia that would invoke the word “poetic.” In Chen Xiaoyun’s works Lash (2004) and Drag (2006) the male protagonist’s suffering and submission seem to be without rhyme or reason. In Lash, as the crack of a whip echoes in the background, we see through the glare of a flashing light a series of close-ups: a naked man dragging a withered tree branch in the dead of night affects a range of expressions, interwoven with shots of human and natural landscapes and the forms of animals. In Drag, a man in a dark room pulls on the end of a rope. As we hear his hurried breathing, the camera wheels to a view of a man’s shadow cast against a wall. The shadow is wearing a long, pointed hat and alternates between tugging at the other end of the rope, then letting it fall slack. There is no question that the shadow is in complete control. After a brief fast-forwarded section, we hear a human voice, low, slow and deep, murmuring something that sounds like an incantation.

The “stories” of Drag and Lash are derived from a single verb, but their manner of expression could not be more different. Lash’s fragmented visual vocabulary leaves a deep impression on the viewer. The narrative played out in Drag, while relatively abundant in comparison with that of Lash, is not very clear, despite an epigram added by Chen Xiaoyun (“You cannot, could not, be in the dark, about all the darkness”). In truth, the epigram only adds to the film’s ambiguity, making it seem as if the film were a visual derivation of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” or a mockery of human desire. Many times, attempts to explain or to clarify an artist’s works have the distinct air of a futile endeavor, but in the pessimistic tone of Lash and Drag we can sense a tendency towards convergence. Moreover, in Chen Xiaoyun’s later works, we discover time and time again the visual keywords and narrative style strongly established in his two earlier works.

Chen Xiaoyun’s later works—I’m a King (2007), Merry Christmas (2006), BI (2007), Love You Big Boss (2007), Night–2.4KM (2009), FIRE–3000KG (2009)—are all, I’m a King and Love You Big Boss excepted, set at night (even the two exceptions take place in night’s close cousin: the well-lit room). Obviously, “night” is one of Chen’s touchstones. In his films, night is a culturally oriented symbol. Night opens the valve on the insomniac’s wild fantasies, and liberates the unspoken words hidden under the surface of reality. Perhaps an appropriate opening line for a Chen Xiaoyun film might be, “Late one evening . . .”

In Merry Christmas, late at night on a street corner a young man beats someone in a Santa costume for no reason that we can discern. The absurdity inherent in this collision between a legendary religious character and the “real world” does not seem to express Chen Xiaoyun’s skepticism towards the genre itself so much as towards those who would advance a kind of deductive logic that insists on the “rationality” of violence in everyday life. In BI (a romanization of a Chinese character which originally referred to a mythical beast, and later came to mean “prison”), on a rainy night out on an open plain a man dressed in rags (à la Psycho) cracks a whip with all his might towards nine trucks of the kind often seen on construction sites. At the end of the film he stands in the mud striking a solemn, stirring pose. He looks like the note from a musical score. Night–2.4KM takes place during the course of a single evening: a group of what look like migrant workers gather on a country road and set off walking in the same direction. It’s worth pointing out that the final shot of Night–2.4KM parodies the “marching production team” shot made famous by Chinese movies from the revolutionary era. The technique imbues Night–2.4KM with a realistic force that transforms it from parable into prophecy. It’s in this that we can discern the reciprocal relationship, torturous but believable nonetheless, that binds together BI and Night–2.4KM.

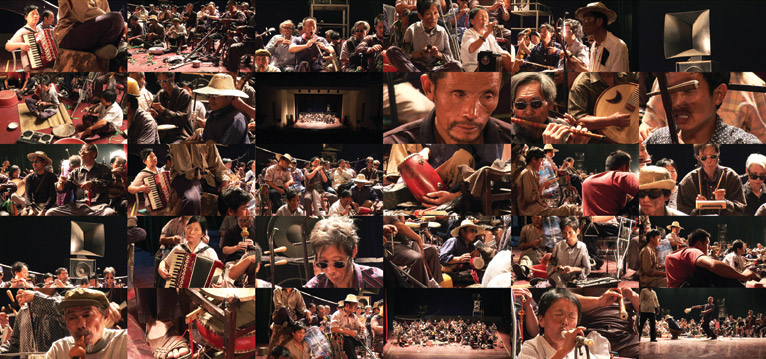

In Love You Big Boss a group of Chinese street performers stage a regrettable performance of the American national anthem using traditional folk instruments. Whether or not this scene is meant to address itself to sensitive political issues is secondary. What’s important is the initial reaction to the state of existence that is “living,” forcing us to reevaluate our own predicament. The piles of burning books and the young people who love burning them in FIRE–3000KG are just like the man locked in a steel cage in I’m a King, proclaiming that he’s the king of the world: each is filled with a hysterical excitement. Chen Xiaoyun is, almost consciously it seems, emphasizing the spiritual symptoms of the disease. “Light” is snuffed out entirely by its symbiotic relationship with the “darkness” (bringing to mind the sunlight enveloping a bamboo forest in Queen Lili’s Garden). The sun will not rise again, and the night becomes an unbreakable iron box.

In these films, the shortest of which is three or four minutes, the longest ten, both the position of the camera and its field of vision constantly remind us to pay attention to Chen Xiaoyun’s role as narrator. The camera also reveals the artist’s favorite rhetorical techniques for building his film’s narrative (his frequent and heartfelt use of close-up shots, for example). In his works, these shots are an ever-thickening layer of adverbs and adjectives that constitute the visual expression of the films’ characters, objects, and behaviors, some shots explicating with meticulously delicate precision, others painting the scene with powerful, intense strokes. However, when this kind of skill is applied to a linear narrative, it’s impossible to avoid a visual style that feels fragmented or even trivial. In works like Chen’s, with their simple plots and fixed scenery, it can feel especially abrupt. It seems as if Chen is doing it on purpose. The natural result of his linear narratives is an unprepossessing, intimate, everyday feel. In a certain physical sense, it seems as if he’s accepting what film can tell us about reality. In another sense, Chen’s narrative style is his attempt to bring us into contact with what he sees from behind the camera, to draw on his experience to construct a linguistic bridge between the marginalized forms, the symbols, and the imagery that his gaze reveals.

Chen Xiaoyun’s recent exhibition at the Beijing branch of ShanghART gallery, Why Life, featured a three-channel video that seems to move him towards a new narrative style. A fourteen-minute long stream of pure information, it attacks the problem of deciphering “life” from multiple angles. On three screens (one main, two secondary) one hundred phrases alternate with a hundred short video clips. Although this work, from which the exhibition takes its title, is structurally reminiscent of Drag, it also elevates, on a visual level, words and phrases to the same level as video, taking into account the screentime of both these sentences and their corresponding video interludes in calculating the length of the films. If one of the distinguishing characteristics of Chen’s earlier works was the hysterical structure of their narrative, then in these works we see the thorough externalization of that previously internal hysteria: static text and moving image jostle for space on the video screens, quick on each other’s heels, the rhythm of the changes outstripping our ability to keep pace. It is, without a doubt, a work designed to overwhelm the senses. It vibrates in harmony with the sympathies of its viewer, each sentence recalling a misfortune that may have befallen them in their own lives. The pictures, sounds, and internal monologues seem to be drawn from victims of suffering and humiliation, like “minor characters” in an epic novel. Although “life” is expressed in these works as a concept only, the words and phrases contained therein continue to draw the works back towards the world of specific language and real emotions.

Compared with Chen Xiaoyun’s earlier works, Why Life confirms the increasingly realistic direction of his creations. But it’s a bizarre sort of confirmation. The words and the phrases of the work enumerate every kind of “normal” phenomenon imaginable, but their sense of urgency seems to address itself not towards any expression of “why life,” but towards evoking within us a genuine collective emotion. This is the source from whence Chen’s works draw their life force, as well as the wellspring of their “defects”: In Why Life there’s one sentence that reads, “Symbols are the only tool by which I profit from the labor of others.” Is Chen here mocking the practice of art, or offering us the formula with which to decode his work? At the very least, in this country of ours, obsessed as it is with silly web comics, symbols are something that couldn’t be easier to enjoy. As such, symbols may be a form of criticism, and the work’s final line, “A gnashing of the teeth,” may itself be a kind of critique.