WOODCUTS IN MODERN CHINA, 1937-2008

| December 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 6

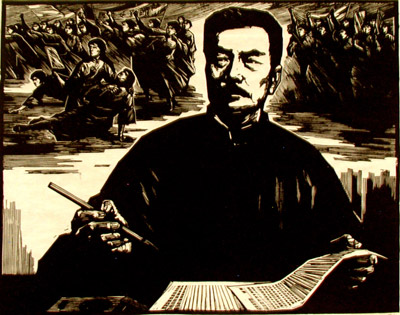

“Woodcuts in Modern China” offers a concise history lesson in two small gem-studded rooms. The exhibition is also conceived as a somewhat more intimate conversation between contemporary woodblock artists and early twentieth-century masters that preceded them. The older work is drawn from the Theodore Herman collection, a trove of more than two hundred prints obtained by the late Hamilton College Professor during a 1948 trip to Shanghai. The newer works were lent for the show by contemporary artists in honor of their predecessors. Woodcuts had a social conscience from the beginning. Lu Xun, the writer and intellectual central to the May Fourth movement, actively promoted the form as a mechanically reproducible means of populist expression that was equally removed from the elitist traditions of ink painting in the East and oil painting in the West. From 1911 to 1949, the developing discipline was caught in a complex political tug-of-war between Communist and Nationalist imagery, as the impulses of avant-garde artists were simultaneously censored and enlisted in the creation of powerful propaganda.

Artists were also experimenting formally with the incorporation of a popular visual vocabulary in their work. Consider the prints of Xu Bing’s thesis advisor, Gu Yuan. His 1940 image Winter School, is a dramatically shaded composition portraying peasant re-education. When shown to his subjects, they responded: “Why are our faces so dark?” As a result, he moved away from his Western realist training and began to employ the strongly contoured outlines of traditional paper cuts and folk art evident in his much more schematic Marriage Registration from four years later. Although the limited freedom that woodblock artists had enjoyed was radically curtailed after 1949, many continued to edge the form in new directions. One of the exhibition’s unique works, Eternal Springtime was printed by Zhao Zongzao in 1960 amidst the turmoil of the Great Leap Forward. This charming six-color composition combines a handful of tightly packed miniature vignettes of women harvesting and processing silk. Its refreshingly modern and cartoonish feel is neither traditional nor realist.

But the truly experimental work came only after liberalization following Mao’s death. Consider Zhao Zongzao’s Land of Peng Lai, completed in 1982, more than two decades after the artist’s busy silk-production montage. The contrast could hardly be more pronounced. The latter piece offers a misty minimalist evocation of the craggy cliff face of Huangshan through the traditional shuiyin technique, which transfers the texture of the wood grain onto the printed surface. Wang Qi also offers a series of progressively experimental landscape prints. Spring Outing (1979) is a lyrical image of two ancient trees with people peppered below almost as a decorative afterthought. Not only is this a bold return to the nature-centric scale of more traditional ink compositions, but Wang removes the heavy Western-influenced borders around the scene, allowing the figures to “float” on the page with the levity and directness of calligraphy. His later Vine Screen (1988) demonstrates this expressionist impulse taken to its logical conclusion—a peopleless portrait of twisting vines that is so dense with lopping lines that it nearly abstract.

The real star of the show’s modern work is Xu Bing. As the catalogue describes, Xu had initially aspired to study in the painting department when he entered the Central Academy in the 1970s but found that he had been assigned to the printmaking department instead. The exhibition offers a rare glimpse of the artist’s thesis project, a series of miniature meditations on modern Chinese life collectively entitled Broken Jade (1977-78). As if to end on a note of radical relevance, the show concludes chronologically with one of Xu Bing’s latest projects, his universal language computer program Book from the Ground (2007-) Yes, there are actually computer kiosks in the exhibition. It is somehow fitting that an art form that developed to communicate with “the masses” would reach its apotheosis in a project that aspires to transcend national language altogether. Sophia Powers