YU YOUHAN: ABSTRACT, CONCRETE

| March 15, 2011 | Post In LEAP 7

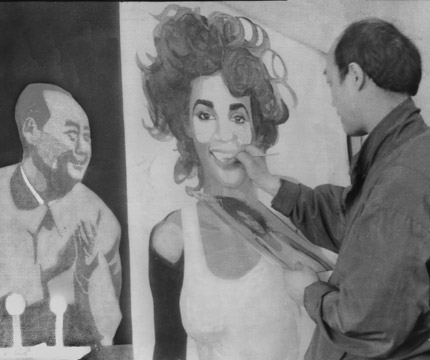

Walking up the grand staircase of the China Club in Hong Kong offers a crash course in contemporary art in China. One after another appear works by artists now seen as key protagonists in a story that was only starting to unfold when the place first opened in 1991. And there, inserted among all the other gestures of pop and cynicism by a group of artists now only too well known, one piece stands out for its unlikely sophistication and finish. That is Yu Youhan’s diptych of Whitney Houston next to Chairman Mao, a painting that suggests an equivalence of fame, and thereby posits a question about the compatibility of two distinct systems, one distinctly evocative of the early 1990s moment when it was created. Absent is the confrontational angst most acutely felt in Wang Guangyi’s best “Great Criticism” canvases, with which they are contemporaneous. Here instead we have the bemused observations of a connoisseur who knows more about the world outside than the prevailing discourse will let on.

This worldlier posture, which many chalk up to Yu Youhan’s Shanghai origins, is gaining renewed notice both in the marketplace and in the historical conversation. On the market front, 2010 was a remarkable year indeed— in two sale seasons, Yu, whose previous auction record, set in 2007, was just less than RMB 1 million, saw two canvases go for over RMB 5 million, and another two for over RMB 3 million. All four of these works date to the years 1992-95.

Although Yu has been present from the very beginning— participating with full billing, for example, in the “China’s New Art, Post-1989” exhibition of 1993, and in the first edition of the Venice Biennale to include Chinese artists later that year— that he is having a moment now seems to suggest something about the current situation, when the commercial culture which most other Chinese pop artists took as a brave new reality seems to have become a mundane truth. Yu’s questions, it seems, were always more about aesthetics and psychology than politics. Suddenly, works like his 1988 Thermos, which turns an ordinary household object into a symbol for an entire condition, or the 2002 collage Just What is it that Makes Today’s Modern Home so Modern and so Appealing? which offers an intelligent dialogue with the British strand of Pop Art most closely associated with Richard Hamilton, seem pressingly prescient.

As a curator and researcher, Hans Ulrich Obrist’s tastes run toward things hidden in plain sight— the unthinkably new, or the living legends whose contributions have yet to get full notice. It was natural then that he would be drawn to Yu, whom he interviewed in mid-September 2009 while in Shanghai for that year’s ShContemporary art fair. We publish their conversation here for the first time. (Philip Tinari)

HUO: Many of China’s avant-garde artists began making art in the 1980s, but it seems you got an early start. You were already painting in the 1970s, right?

YYH: I still have a piece from 1973, a girl’s portrait, typically expressionist. But I certainly haven’t continued to paint that way; I often change my style.

HUO: You were making Neo-expressionist works in the 1970s.

YYH: I had seen Fauvist works before, thanks to a neighbor of mine. Although he wasn’t my teacher, I had seen some of his works, and some paintings he had hanging on his wall. In a sense, then, he was my teacher, although he had never instructed me with actual language (however, his son was a good friend of mine).

HUO: I’ve noticed a strange phenomenon, that whereas a lot of artists suddenly appeared after the 1980s in China, it’s really difficult to find any from before.

YYH: Modern art was prohibited during the Mao era, but in Shanghai, Lin Fengmian, Liu Haisu, Wu Dayu and others were around since the 1930s.

HUO: Did you know them? Have you seen their work?

YYH: I didn’t know them, and original copies of their work were hard to come by. But that old neighbor of mine, he was a friend of theirs. He was thrown in jail in 1955 or 1956, and it was a long time before they let him out. Now he’s already passed away. His son is still around, as are his paintings, though very rarely does he take them out and show others. I think his work is good, though, really good.

HUO: What was it about his work that you liked?

YYH: It’s free. The broad strokes. It’s distinctive. It looks like the work of a true master. I like that there are few figures, and abundant landscapes.

HUO: I suppose it was difficult to come across any abstract work in China at the time?

YYH: At that time, no, there wasn’t much. Yet I had seen some abstract work, and felt that I could give it a try myself. I had seen two or three paintings by Wu Dayu on exhibition. I still remember one of them, titled Morning in the Park. There was also a teacher from the Arts and Design Academy, eight years my senior, named Miao Pengfei. He’s in Macau now. I saw an abstract piece at his place, once.

HUO: In the West, there were abstractionist movements in the early twentieth century, but it seems there weren’t in China, correct?

YYH: Correct. I knew about Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky, but only from books.

HUO: Where did you discover your own personal form of abstraction?

YYH: In an attempt to modernize my painting, I tried using all sorts of abstract styles over a span of four or five years. In the end, I settled on this particular style (referring to the “Circle” series).

HUO: Was this change in creative style rooted in a different perspective from which you looked at things, or in a change in you as a person?

YYH: As a person, I hadn’t changed. The outside had changed. The country had changed. When Mao was alive, the political climate was different. There were all sorts of political movements and programs.

HUO: Mao probably didn’t like abstract art, did he?

YYH: It was once argued that abstract art moved against the times, but at that time Mao had already passed away. My abstract period lasted about eight years, from 1980 to 1988. By then the national situation had changed yet again. During Opening and Reform a lot of things happened. There was inflation, rising prices, corruption among officials, etc. Young people had great hopes for the progress of the country. Around then I bought a pocket book on Pop Art. I remember thinking how great it was, how this style could unify my painting with the changing times.

HUO: Actually, abstraction is a microcosm of society. Mondrian was also obsessed with how the ideal society would be.

YYH: Take my “Circle” series. Not only is it concerned with society, but also with nature and human thought. Everything is contained within. Right now, you are interviewing me. But after a while, I start thinking about something else. And then you come back to interviewing me. Our thoughts are in a constant state of change…

HUO: How many of these paintings did you make?

YYH: More than twenty, all part of this one series. On a spiritual level, my greatest inspiration came from Laozi’s Tao Te Qing, which I hadn’t read until the 1980s. When I did read it, I fell enraptured by the basic ideas within. I hope that my own work can be like Laozi’s. The idea that the universe is alive, in a permanent state of change. If I were to have a spiritual teacher, then it would probably be Laozi.

HUO: In 1988 you changed, going from abstract to pop. From general flows to specific themes, from abstract to concrete. What caused this change?

YYH: The change came about for a few reasons. For one, I had already made abstract paintings. Suppose I still did that up to this day; of course I would have gradually modified its outward appearance. I am somebody who likes change. Take, for example, the “Circle” series. If I paint a black circle today, then next time I’ll probably make it white. After the white one is finished, I might just paint a black one again. I am not like a scientist who will research the same thing for twenty or even fifty years, research it to death. I don’t want to take art and wring it dry. When the “flowers of my soul” bud and bloom, then I am happy. Then I turn back to see what other stimuli society has to offer, and I change my ways to meet their challenges. For me, it’s a very natural process.

HUO: What do you consider your most seminal work?

YYH: It’s a chair on top of which I painted a bunch of abstract little circles. There’s another, based on The Grand Odalisque by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. I painted over the flowers in the original, and over the woman’s body as well. There’s also Four Renminbi. All of these were made in 1988.

HUO: I went to see Biljana Ciric’s exhibition yesterday (“History in the Making: Shanghai 1979-2009”), and noticed that they put your abstract works together with your pop works. They didn’t clash at all, but rather, they were marvelous together, and the room where they were exhibited became the focal point of the show. Can you talk a little bit about your pop art, about how it contains both Chinese and Western elements?

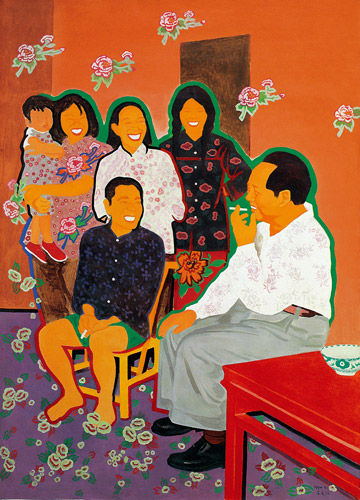

YYH: My Mao paintings employ a contrast between China and the West, the two great ruling powers of the world we inhabit. When I want to express this world, I bring these two symbols together. Naturally, there is something political about all this.

HUO: Are these photos very important to you?

YYH: In the process of making the “Ah, Us!” works, I would collect a lot of these little photos, pictures of young girls and beautiful women. The government had published two books. One was a collection of photos of Mao published just after he passed away. The other was the old Nationalities Pictorial, sold for RMB 5 at kiosks, that was published years after Mao’s passing but still was mostly just pictures of Mao. What I used came primarily from these two photo albums. I had just started to paint Mao when one day I came across this photo of the beautiful Whitney Houston. I figured it would be pretty interesting to paint Mao right next to her. So I dug around a bit, and voila, found a photo of him clapping. (Mao with Whitney)

HUO: Pop art in the West already has a long history. What’s the relationship between Chinese pop art and the West? Who else makes pop art in China?

YYH: American pop art painted the stuff of everyday life, consumer products and pop stars. In China, our political life was so rich, so fulfilling, so very formidable, so stimulating. Today, a lot of young artists’ work is full of the relationship between politics and control. When we discovered the path that pop art provided us, and when we began to take that path, it was all very natural, and with a hoot and a holler we charged forward. I was six when China was liberated, but over thirty when Mao Zedong passed away. Essentially, then, my life was spent during the Mao era, when there were so many movements, political movements and programs that never ceased. And so if I want to express my youth, then I’ve no choice but to paint Mao, who was the very center of that era. In painting Mao, I’m actually painting that period of my life.

HUO: There are quite a few pop artists in China, like Wang Guangyi, for example. What’s your relationship with them like?

YYH: Generally speaking, we’ve nothing to do with each other. I am here, he is there. I’ve never seen him, he’s never seen me. The only one I’ve had some contact with has been Wang Ziwei, who was my student. He inspired me to paint my very first Mao. He’s now in the West, signed to three different galleries. Basically, he paints in the style of Lichtenstein. Me, I paint like Chagall. Chagall painted out his experiences as a youth in Russia. We share some things. When I paint Mao, I paint the memories of my youth. The only difference is stylistic.

HUO: China is becoming very urbanized, all the way down to small villages. Have you ever painted these little townscapes?

YYH: Not very often. I did paint some after the year 2000, the “Yimeng Shan” series. When I see all this large-scale urban construction, I really don’t feel that well. I feel like the expression of a young girl in a painting, lost and unsure what to do. So many high-rises. I call them “empty shells.” This painting is an expression of my discontent with all these buildings. And so I went to Shandong, one of the poorest places is China, sometime around 2002.

HUO: So you took your students to Yimeng Shan to sketch and take photos to bring back, then began the “Yimeng Shan” series, am I right?

YYH: I didn’t bring a single student with me, but in the name of bringing students later on, we went ahead and did a little research.

HUO: Why would you want to paint these landscapes?

YYH: Actually, these landscapes are just a bunch of rocks and mud. When you are surrounded by “empty shells”… you know, then you see real earth, and small, but old mountains— not like those new, towering, rock-hard mountains like Everest, but little cobblestone-like mountains, only one or two hundred meters tall. I feel close to these mountains. Mountains like Everest I’ve no hope of climbing, but these mountains, inside these mountains there are entire fields, where you can plant yams and potatoes, where you’ll see two girls pass by with hoes on their shoulders, and old women working away, too. The people there are warm and sincere. Life there is what life was like before we had been alienated, when we were pure of mind. I find it heartwarming.