WILSON SHIEH: MORTAL COIL

| May 26, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

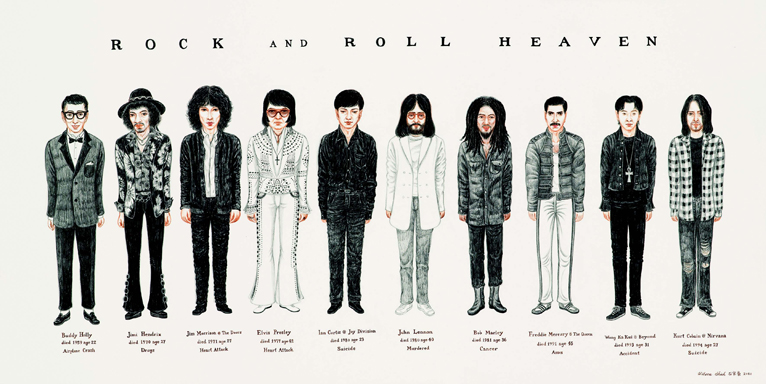

Venturing out under a gray sky to see Wilson Shieh’s new exhibition, “Mortal Coil,” I found similarly dark, muted hues upon arrival. The Twenty-Eight Hong Kong Governors sketches the formal portraits of former Hong Kong governors in shades of brown pencil. Catalogued in tiny print beneath each figure is the governor’s name and his dates in office, along with Hong Kong streets and buildings named in his honor. The works are not framed, intimating the suspended narrative of colonial government, and the white space surrounding the figures harkens back to the artist’s training in traditional Chinese painting. Rock And Roll Heaven, Famous Hong Kong Film Actors, Some Jazz Singers, and the other series in the exhibition share compositional similarities, all presenting groups of full-body portraits on designated themes.

Wealth and Position Are Like Floating Clouds and Gentlemen Love Wealth, But Make It In A Righteous Way are two small drawings produced with colored pencils. The former depicts a grand banquet—a round table covered in an assortment of Chaozhou recipes; the latter a leisurely scene with the shadows of tree branches dancing about on the ground. A text to accompany the drawings reads: “The master said: ‘eating coarse rice, drinking water, using one’s elbow for a pillow— this is where joy is to be found. Wealth and rank attained through immoral means have as much to do with me as the passing clouds.’” The picture appears to be of Li Ka-shing. The title— his once public slogan—provides a sharp contrast between the Confucian ethical standard for pious contentment and the status of the richest man in Hong Kong.

“Mortal Coil” looks as if it is a research-based exhibition, but the assemblage of related cultural symbols and wiki-esque accumulation of data are not so much attributable to research as they are to a kind of collectomania on display. When figures are stripped of their historical, literary, or cinematic backgrounds, infinite possibilities should emerge. But with these works, the new “stage” on which governors and celebrities stand is empty, exposing a sealed-off historical narrative. Rather than offer a multiplicity of ways into the subject matter at hand, the symbols become specters, “non-physical bodies” sweeping across our senses like Rancière’s imageless images: mere signifiers that refer back to the image itself. Thus, “Mortal Coil” exhibits a certain kind of inertia: political criticism through symbols, of formal reproduction, of the academy’s position with regard to Hong Kong’s “colonial narrative.”

When confronted with the historical reality of East meets West during the colonial era, many believed that the identity of the Hong Kong people was destined to be divided. Applying this line of logic to the pieces in Wilson Shieh’s earlier exhibition, “Fitting Room,” would mean that Chow Yun-fat’s Western-style suit ought to have been hiding his Cantonese roots, and that Maggie Cheung’s qipao garb was actually concealing a blonde-haired, blue-eyed interior. The fetishist disavowal of identity is exposed by the nakedness waiting just beneath these meticulously tidy outfits. From within that hypothetical binary opposition between East and West, Hong Kong people feel nostalgia for what has not yet disappeared, or in Abbas’s terms, a “politics of disappearance.” Unfortunately, the governor portraits in “Mortal Coil” and Hong Kong singers from the 1970s and 1980s only serve to recreate a social reality prior to the return of Hong Kong— without, in the end, elucidating much more. Venus Lau