ZHANG HUI’S HIDDEN GAZE

| May 3, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

An important member of the “Post-Sense Sensibility” group of the 1990s, Zhang Hui has worked in media including installation, theater, and performance art. And then, five or six years ago, he turned the larger part of his attention to painting. Zhang shares some thoughts with LEAP about this shift in his practice.

I’ve told this story before. We used to have a dog that my daughter really adored. After we’d had it for seven years, the dog got sick. We took it to Peking University Veterinary Hospital, but it was no use, and the dog died. We buried it by the highway on the outskirts of Beijing. The next year, my daughter wanted to go back and look, but when we got to the spot, we couldn’t find where we had buried the dog. The grass around the area had grown tall, and every spot looked the same. I remembered that we had scratched out a mark on a tree next to the makeshift grave. We looked for the mark, and we found the spot. Right then, I noticed something really out of the ordinary. The grass over the spot was taller, more verdant than the grass surrounding it, because the dog’s body was buried beneath. That was when I started to become really interested in this kind of thing.

At first glance, the reality we observe each day is more or less the same. But in some places the grass flourishes. People who are perceptive (or, you could say, people with a history) know where the grass flourishes. In the same vein, you and I aren’t the same person, just like no two people are exactly the same, because no two people share the same heart. There are two kinds of history: cold and warm. Cold history is knowledge. Warm history is memory and emotion. The two kinds of history woven together make a world, so every person’s description of it will be different. I respect this kind of description, and I paint this kind of painting.

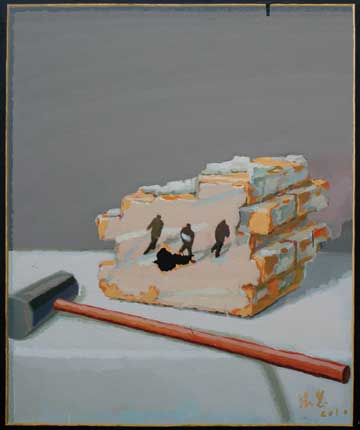

For example, with the “Mural” series, I carefully painted a wall. Then on top of the wall I painted an ordinary firefighting tableau. I left the color of the brick at the boundaries of the painting untouched. The spots of black in the middle looked like spots where the surface of the wall had peeled away. What was left after the “Mural” was peeled away? Was it a wall? Or just blackness? In the second “Mural” painting, the imaginary wall had been demolished. Thus parts of the wall made their appearance in the painting in another form.

The setting for Happy New Year— a restaurant in an affluent part of Beijing— was also quite simple. A waiter carrying drinks stands in the foreground. Nearly everyone in the background is wearing short sleeves. The painting was done according to a photograph taken in October of 2009. When the first snow fell that winter, I made sure that it snowed in the painting too, just as natural law would have it.

So, as far as I’m concerned, the most important thing about finishing a painting is not the product, but the relationships that the work evokes. If you look closely, you’ll see that all of my paintings have a beginning and an end. A highbrow way to say that would be that they all have “temporality.” When I finish a painting for the first time, I put some serious thought into what the next step might be. It’s a little like the painting is asking me questions, and I’m trying to think of the answers. I’ve always worked to use my experience and knowledge to inquire into what I’ve yet to learn. I’m not going to put any more work into something I already know, as I’ve already explored the depths of what I know. Trying to integrate those things that I already know, and using this foundation to work on what I do not, is a process I call “seeing.” If you look at my paintings, you’ll see they’re all about the minutiae of family life and scenes from the everyday. I hope to use these environments to draw out the things we don’t know.

In this process, I’m not afraid of being too precise. Actually, I always want to be more precise, because precision is a challenge for me. Going forward I want to work on expressing myself more clearly and simply. It’s like meditation. Even though I’m not an expert on meditation, I feel like the idea of “clear yet confused” resonates with what I hope to reach. Looking at the surface, it might be simple to describe, but the space beyond is vast. The further inside you move, the more wrong things feel, and the space expands with every step. Before I would always want to make the space as big as I could, to make things extremely complex. Now I want to keep it simple.

My current projects are an exercise in correcting past mistakes. Because the key to painting is whether or not you achieve what you intend to produce. If you know what you’re doing, everything will fall into place. It’s not necessarily important to be relaxed. A bad painting is a bad painting, even when painted in a calm state. Though the great painter Bada Shanren was calm, and never had a single stroke out of place. Whether it’s people or paintings, the first thing is to know what you’re doing. The second is being reliable. Neither is innate, kind of like staying on key when you’re singing. But whether or not you sing well is innate, and beyond our ability to decide.

I admit that old paintings can die, and this can happen repeatedly. But artists will always be with us, and their works continue to produce new meanings. What is painting? How should we paint? These are questions that every modern painter should think about. The works of our predecessors are like the earth beneath our feet. Layers lie beneath the surface. They don’t accumulate in neat parallel lines, and all of them can enter into your thinking.

The core qualities of humanity don’t really change, and we all experience the most basic emotions, like sorrow, pain, happiness, and envy. What’s most important for artists is their ability to observe, and what they observe can naturally merge with a structure. Vision is about the eyes and the relationship between gazes. Works have a gaze, behind which the artist hides, and the viewer holds a gaze as well. The space between these two is especially interesting. For example, if I paint a tree, the people may simply see a tree, but overlook the relationship between the tree and I. A close observer, however, will see both. Seeing the tree, the observer thinks of the actual tree, and at the same time envisions me seeing the tree, and sees my work. So I’ve left a trace. Before I used to do it on purpose, but now I think deliberately about how to make it natural. It’s just like practicing calligraphy. When you first start, you copy forms out of a book, but once you reach a certain level it just comes naturally. Because you’re always thinking, sometimes when things become a little clearer, you see that, in reality, doubts are everywhere. If you carry them in your heart, they can emerge in your vision.