WANG JIANWEI: MAN IN-BETWEEN

| June 22, 2011 | Post In LEAP 9

IF THERE IS ONE ARTIST apt to leave pundits chewing their pencils, it is Wang Jianwei. He is surely the first to have occupied a 2,500-square-meter exhibition hall— indeed any exhibition hall— with several thousand basketballs in the name of art. “He’s complicated,” remarked a curator on recent mention of his name; “Ah, yes” a young painter replied, with unusual solemnity. Accounts of Wang’s work invariably voice an admission of its “difficulty.” Against those of other contemporary artists, it seems his oeuvre is notorious for, even characterized by, complexity. In an interview, Wang himself says, “I often receive critiques from the media and public that my work is very difficult, in an artistic manner… that I’m doing something that’s going very deep into the theory of art. But I don’t think that’s what I’m doing. I think what I’m doing is presenting the world as I see it… as a place where many different things— opposite things— are juxtaposed.” Thus, an artist’s reputation merges perfectly with his views: that he simply portrays the world. As Diego Rivera’s maxim goes, “I paint what I see.”

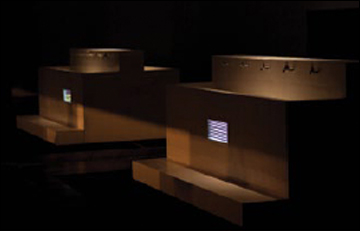

“Yellow Signal,” Wang Jianwei’s massive exhibition, currently at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, makes clear, however, that he is no longer a painter. This four-month, four-chapter show is arguably his most ambitious project to date, and the most significant since his “Hostage” occupied the entirety of Shanghai’s Zendai Museum of Modern Art in 2008. To approach the entrance to part one, Making Do With Fakes, was to feel uncertain regarding what lay beyond. The first impression was not visual, but aural; from behind a title panel positioned in the doorway of the exhibition space radiated a slow, pulsing bass tone from which there sometimes surfaced an anguished human wail. At other times, disconnected clanking or strange sweeping sounds would interject sharply for a few seconds, before the ominous reverberation prevailed again. Disarmed or perhaps enticed by this powerful soundscape, upon entering the dark hall one was met with the architecture of Wang’s conception: a series of four successive “gates” or portals erected across the exhibition space at a height just low enough to feel slightly oppressive as one passed beneath them. Onto either side of each was projected a different video loop; these showed human action unfolding in settings such as a courtroom, a dormitory and a ping-pong hall. The entire installation was subtly illuminated by amber-colored theatre lamps mounted to right and left on the tops of the portals in groups of four: “yellow signals.”

Making Do With Fakes transformed the atmosphere of the space into something more black box than white cube; but rather than being drawn visually to a single screen, the gaze of the visitor was fractured by the simultaneous presence of multiple projections. Although based on real life, the viewer encountered a kind of “unreality.” Each screen revealed a matte gray oblong space with white lighting that cast unnatural shadows around fine-tuned actors’ movements. Outside these arenas, yet still within the first artificial layer of the exhibition hall, there was also a feeling of disjuncture between the overbearing aural and visual surroundings, the linear path presented through the portals and, conversely, the freedom to move through at leisure. Such was the spectacle of the installation and the degree to which it had been orchestrated, that it implied an unequal relationship between the audience and the artist-as-author, or omniscient director, of the experience. The emotional tenor was unclear, and the title, Making Do With Fakes, bore an unclear relation to the display.

Before any discussion of the conceptual fabric of “Yellow Signal” begins, experiential factors, layers, and questions flood in to intrude on attempts at interpretation. This is perhaps why Wang Jianwei is sometimes accused of deliberately “mystifying” simple ideas with complicated appearances. If, on the other hand, we view his work based on his reputation for being well-read in philosophy, coupled with his deep personal experience of social change in China, then his artworks may be treated as highly finished statements. If Wang’s works are to be interpreted as “complete” in the sense of being a successful end product of his deep conceptual thought, the underlying concepts must still be unraveled and understood. In other words, to imagine the self-satisfaction of the artist is to render him distant from his audience: an unseen orchestrator of dramatic and ungraspable artistic events. Probing what Wang is trying to achieve through his work, Karen Smith is careful to deliver a sense of his personal quest for accuracy of meaning, along with a resistance toward reducing art and culture to definitive categories. Rather than seeing each new piece as a form of “arrival,” we can contemplate the evolving route of the artist’s journey.

Wang Jianwei himself cites stumbling blocks that make his work seem “difficult”— in short, the contemporary culture of “seeing.” He objects to thinking of contemporary art as “visual” art, as truth is not uncovered solely with the eyes, nor strictly through exhibition texts; for Wang, these are reductive expectations. “I think that this has always been an issue in Chinese contemporary art— the way of seeing… As an artist I have the responsibility to try to challenge that.” He describes himself not as a creator but a collector of images; “I’m not really creating anything that nobody has ever seen before…it’s reenacted, but it’s already there… Sometimes what we can see is not necessarily everything that influences us, and there are a lot of things…that are not existing with us at the same time. Sometimes it’s in the future; it’s the history, the culture, and what I do is put all these things together at the same time and in the same space.” In line with the experimental syntax of his work, Wang has coined his own idiom for “Yellow Signal” (huang deng gongtongti), which refers to the yellow light and the idea of hybridity, or a combination of different elements. Against the dissection of perception, he envisions an exhibition that combines dissimilar “ways of seeing.” This entire exhibition, he says, aims to address the issue of belief in singular modes of understanding or encounter, asking the question, “How do you combine all of your visual experiences?” The approach, then, should be holistic: to see his work as a body of experimental endeavor, not to venerate works as successive “arrivals.” The multilayered experience of this exhibition must then be seen as a hybrid— not reductive— one that tries to mimic real experience. How does “Yellow Signal,” then, address itself to hybridity and the “way of seeing,” and how does it relate in this sense to his other works?

“Process” has, from the outset, been integral to Wang Jianwei’s work. It is a factor of his consistent aim to connect with society and to reflect people amid an unending state of sociocultural shift. For Wang, process is a noumenon— in Kant’s formulation, something valid in and of itself— rather than a tool; to look only at the result is insufficient, and risks “missing a lot of interesting things that happen along the way.” Only process, therefore, can adequately represent experiential reality: “If you disregard the process, then there’s nothing, because the process is the experience.” The dimension of lived experience is crucial to Wang’s practice. We find these concepts in his earliest video works, which employ the documentary capacity of the medium. Circulation—Sowing and Harvesting (1994) records a period spent growing barley alongside peasant farmers.

Seventeen years after that video, the idea of process is bound tightly to the “way of seeing” Wang Jianwei pursues in “Yellow Signal.” Whereas for Circulation the process was contained within the action of the video, Wang’s practice now has expanded beyond the limitations of this frame. The form of “Yellow Signal” reveals how a processual way of seeing has been built into the show’s physical and temporal design. Furthermore, there is a prescriptive dimension offered up to the audience, who must return to the venue again and again to witness all four stages of its realization. As it is impossible to see it all at once or treat it as a single outcome, the exhibition dictates an extended process of encounter with art, seeking to enter into the visitors’ lives as a recurrent feature of their experience. For Wang, part of the success of Circulation was the way the harvest appeared and could be understood as a product of experience, “not like the blankness after an exhibition.” The way in which “Yellow Signal” plays out is an attempt again to mitigate that “blankness” by resisting the possibility of a singular, empty endpoint unqualified by experience.

That “Yellow Signal” embodies a complex mixture of new media comes as no surprise. Since 2000, Wang Jianwei has employed physical theater, video, animation, sculpture, documentary, performance and playwriting in an exploration of a unique experimental territory that generates a distinct “way of seeing.” Wang insists that this experimentation is not for the sake of the media itself; instead, it must “be equivalent to the problem I am addressing.” The problem Wang articulates relative to “Yellow Signal” is that of visual artistic convention— eyesight and words— to explain and experience art. Huang’s idiom (huang deng gongtongti) reflects the fact that he cannot “bring the audience to that position that I want them to be in” through a single, straightforward channel. Within the compound space of the exhibition, he aims to exploit the potential for a diverse range of relationships that reflect the non-linear nature of real experience and cultural production.

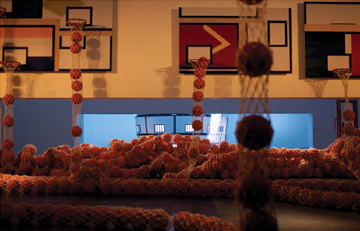

In this respect, “Yellow Signal” thus far shows both continuities and ruptures with Wang Jianwei’s past work. In the downstairs section of the four-part “Hostage” were strange sculptures the centerpiece of which, General Report, was an elongated conglomeration of colored pipes topped with heavy, shiny white gloop. Upstairs, Money, a half-hour film installation, showed performers reenacting life in a Cultural Revolution-era commune. Contained within three stage-set walls, this artificial cinematic narrative is finally exploded by some unseen force from the outside. Both “Hostage” and “Yellow Signal” feature the juxtaposition of video projection and sculptural installation, though in “Yellow Signal” the first chapter featured multiple projections, and the second, We Know What We Are Doing, is weighted towards physical installation. Here, the first portal is blocked by a huge mass of netting lying in a deep, coiled pile along the floor, stuffed with a surreal catch of basketballs. Beyond this barrier, lengths of netting snake down from hoops mounted on the wall, channeling more basketballs towards it, queued up in the process of dropping down as if a feeding movement has been suspended. A video projection, a large cylindrical structure, institutional plumbing fixtures, and small taped-over screens constitute the rest of the installation. In comparing the balance of media in “Hostage” and “Yellow Signal,” the focus is never on the specificity of the assembled media, its language and/or production, but as Wang puts it, on the making of an artwork “using some kind of material.” His is an understanding of art as a non-material cognitive attitude, and a hope for its liberation from a “closed system.” The presence of multiple media is directed, therefore, at the importance of “generality,” of art’s potential to interact with ordinary experience, and at the same level. The hybrid environment triggered by varied media in both “Hostage” and, currently, “Yellow Signal,” thus shares non-specificity in common with life’s experience, which is itself the unbalanced sum of different parts. This versatility is also the biggest limitation of multimedia, Wang admits; the challenge is how to orchestrate it and thus spare what he obliquely refers to as “the curse of mixed media.”

Wang Jianwei’s use of multimedia is invaluable to him for another reason: it can activate and maintain a space that is not clearly defined. This he terms the “gray zone” or the “third,” “fuzzy,” or “in-between” space, the innate characteristics of which make it uniquely productive for the artist’s system of thought. The gray zone, for example, is incapable of providing a linear narrative or a finite reading; it is a realm of ambiguity and tension. As both state and site, it is the centrifugal premise of “Yellow Signal.” The yellow or amber light epitomizes everyday transience; essential, habitual, recurrent but impermanent, it seems the perfect hinge to connect Wang’s fascination with the in-between and his loyalty to ordinary existence. The moment governed by the yellow signal is a site of transformation, adjustment and slippage; an intermediate place, full because its content has not yet been distilled into one outcome: “stop” or “go,” restriction or freedom.

His previous works reveal varying shades of the gray zone. Early on, Living Elsewhere (1998) recorded the lives of migrant workers squatting in unfinished villas on the fringes of Chengdu. These drifting farmers inhabit a realm between jobs, between city and countryside, and between old and new ways of life; their chosen shelter is an ideological “shell” that itself lies somewhere between ruin and aspiration. Their gray zone is a physical one, a reality they inhabit. Last year, Welcome to the Desert of the Real exploited the multiple dimensions conjured by mixed media to evoke an unstable territory between reality and illusion, concrete and abstract. Unable to find his niche after moving to the city, a sixteen year-old boy grows to inhabit a virtual reality: the internet. Loss of a sense of the boundary separating this and actual reality results in the murder of his mother. The narrative “shatters” as it unfolds, its thread split between live physical performance, animation, video and short film channels. This performance therefore succeeded in positing two simultaneous “gray zones” or dissolutions of bounded understanding: that of the protagonist’s virtual reality, and another, relative to the perception of the audience, whose view of the action was ruptured by intervals of abstract geometric shapes playing on screens.

What is so compelling about the in-between for Wang Jianwei? Why the pursuit of hybridity and new “ways of seeing”? He explains his conviction that the gray zone is neglected in contemporary sociopolitical culture, a place of black and white. This obsession with clarity cultivates safety, and safety rejects challenge or uncertainty; this “is not just a situation but something much bigger.” Ask him if he feels the relationship with society is stable and, he responds with another question: “Do you feel safe in the exhibition hall with ‘Yellow Signal’?” The exhibition purports to establish a state of what might be called “fertile instability”— something society lacks. This, the artist says, is the politics of contemporary art, to create an awareness of an alternate “way of seeing,” a state of productive ambiguity. On this note, contemporary art has only just begun, and the fifty-four year-old artist feels only twenty-five— marking the birth of his exposure to contemporary thinking. One might add that the experimental artist himself occupies an in-between location somewhere between curiosity, achievement, and failure. Internal Conflict, the third chapter of “Yellow Signal,” poses the questions Wang Jianwei wants to ask, and also the very question that he would like to be asked.