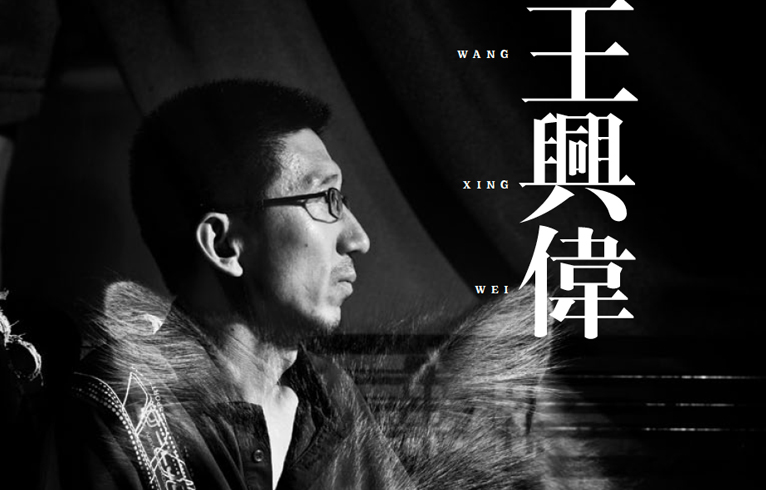

WANG XINGWEI: TRUE OR FALSE?

| August 8, 2011 | Post In LEAP 9

Wang Xingwei was born in 1969 in Shenyang, Liaoning Province. He did not come from an artistic family; rather, as a natural-born lover of painting, he ended up in all sorts of interest groups and classes. He took an exam and wound up in the art department of Shenyang Normal University. Growing up in an environment devoid any connection to art, he became intrigued by foreign art books in bookstores. He purchased books of paintings by Theodore Gericault and Eugene Delacroix; not long afterward, his younger brother, Wang Xingjie, who would also later become a painter, bought him a book of Cezanne’s paintings. The world revealed to Wang by these outwardly plain catalogues of Western artists was vastly different from urban life in northern China in the 1980s.

At the time, the ’85 New Wave in Chinese art— what later would be dubbed the birth of the Chinese avant-garde— had already begun to emerge. Young people were fervently curious about novel, foreign lifestyles. They wishfully pursued an idealistic, individualistic liberation and spiritual freedom as a means to escape and avoid an extremely impoverished reality. From books to music and other aspects of cultural life and entertainment, and even including styles of dress and speech, everyone wanted to do things differently.

Wang Xingwei’s innate disposition led him to an interest in the fragments of deeper spiritual content within the burgeoning new culture. He was not overly driven to external displays of individuality. He did for a time fancy high-end Western clothing, and once cut his hair to resemble an orange soccer ball, but for the most part he was not one to conform to popular trends. That he still wears hand-knit woolen long johns is widely known; Wang seeks his self-definition in the realms of intellect and spirit, not fashion.

The conclusion of the 1980s had an incalculable influence on Wang Xingwei’s generation. This influence largely took forms imperceptible to the participants and onlookers. It drove him toward a pursuit that he remains entangled in today: painting. He disassembled and ruminated over the historical pillars of the art form, one by one, maintaining a skeptical attitude throughout. He evaluated knowledge and theory through personal experience and engaged in diligent self-analysis. Skepticism and a demand for authenticity became guiding components of his life and work. Later, Wang would say that one’s existence intrinsically furnishes a paramount question that includes all primeval challenges and all invisible but omnipresent structures of thought, because normal life avoids contact with authenticity.

In 1993 and 1994, after leaving behind the topical art that had spread throughout art schools in the early 1990s, Wang Xingwei produced some autobiographical works, such as To Hurt and Dawn. These works exhibited normal qualities of composition, color, imagery and atmosphere, expressing the experience of ordinary, individual life with a sense of weight. They possessed the fresh, distinctive look of Wang’s work, and more importantly, they marked the beginning of his exploration of a formal issue in the painting medium: the way in which the state and behavior of people and the supposition of a staged setting introduce performance and presumption into the reenacted reality of a painting.

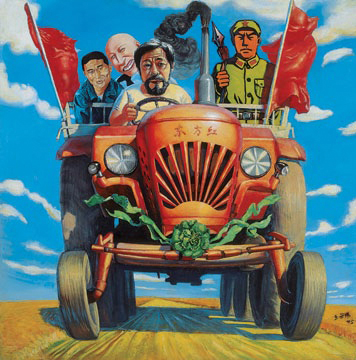

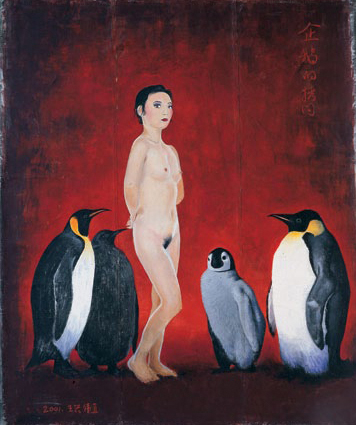

In 1995, Wang Xingwei began to address art history in his work. Continuing to employ methods of presumption and postulation, speaking in today’s terms, he traversed and parodied artwork from different time periods, including satirical treatments of “Post-1989” trends in Chinese art. His paintings from this period were still powerfully composed, richly colored and designed, and abundantly humorous and fun. Beginning in 1997, relatively veiled and equivocal content occasionally appeared in his work. The emergence of more ambiguous imagery, including penguins and pandas, marked his work at the turn of the millennium. The style of these paintings began to feature less rigorous composition as well as the visual characteristics of commercial painting. This period marked a transition to a new set of principles rooted in the search for means of casting off both the reliance on artistic styles and the consolidation of the value of “artist” status.

Wang Xingwei was questioning the use of color, style, and other fundamental elements of painting. It was as if he were abandoning his mature, individual style to return to square one in the study of painting. This proved to be the case, as his work progressed from stiff, bright and hasty to mature, consummate, harmonious, and exquisite over the course of the ensuing several years. Wang had truly changed his approach to being a painter.

The early Wang Xingwei had an excellent capacity for realistic portrayal, a nimble and keen intellect, and an influential sense of humor. Though his art was once pejoratively likened to the skits of comedian Zhao Benshan, he was eventually accepted as a painter with a bright future. As for the later Wang Xingwei, some suspected him of deliberate obfuscation, while others went further, suggesting that he was a modern-day Tamara de Lempicka, relying on his modest reputation to justify all sorts of foolish experimentation in painting. All of these reasonable critiques were raised throughout the Chinese art world following Wang’s transformation.

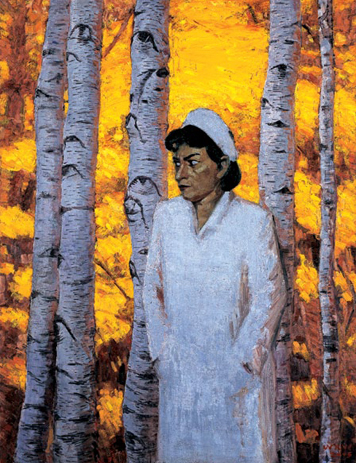

But this later Wang Xingwei was not merely problematizing his own work; he was exploring new possibilities within the realm of painting. Facing the diversification of art media, Wang Xingwei decided to persist as a painter, and he sought to extend and expand the connotations of the medium. He started with watercolor propaganda posters, commercial painting, and pedagogical painting exercises, but he also riffed on Fontana and Courbet. His subject material skipped freely from revolutionary history paintings to ironic self-portraits. By 2003, Wang had relocated to Shanghai, where he began painting on roof tiles, utilizing the naturally curved surface of the material to create inverted reflections and wave effects. These effects were founded on the same reasoning that led the painter to begin portraying sailors, stewardesses, nurses and other similar characters in 2005. Portrayals can be either affirmative or subversive. The crooked line of a soccer field on a tile, a hunter firing his gun in a warped field, a character’s betrayal of the status conferred by the uniform she wears: these were among Wang’s subversive portrayals.

It was in this period that Wang Xingwei developed a parasitic theory of style, piggy-backing on Lempicka, Art Deco, and cartoon. This sort of parasitism is not simply borrowing. Rather, because the target of emulation possesses a distinct visual style and a symbolic identity and significance, Wang’s approach provides a continued, resolute dislodging and deconstruction of customary significance within painting, exposing the inevitable implications that present themselves with each stroke of every painter’s brush.

The contents of Wang Xingwei’s paintings are merely target practice for his exploration of painting and reality. The content of his 2008 series of four paintings of Comrade Xiao He and his 2010 series of five Untitled (Old Lady) paintings is not intrinsically rich in significance, nor does each successive painting demonstrate an evolutionary process; rather, they present a lively, complex art form, the one we call “painting.” The artist’s own words most clearly express this idea:

In life, art might be an antibody, an enemy of the animal aspect of living people. It’s indispensable. This antibody is reliant upon real circumstances rather than any historical order. The modern conventions of art history are not the most fundamental. The reason I have not proceeded on the basis of abstract logical ideas, but rather mixed them together with the imagery of painting, is that I want them to retain the characteristics of an instantiation. As soon as a statement becomes a kind of principle, it’s extremely inconvenient. Principles should also be instantiations; this is the only way for their specific attributes to be stated accurately. Conceptual art is like this as well, but it possesses a particular exterior, and I think this exterior is inconvenient. Also, first making a value judgment and then giving it a form— this sequence is problematic. If you only talk about meaning, you remain unaware of the orientation that underlies its foundation. I’ve always been very interested in commercial painting because in a different sense it strictly and completely avoids these issues. It achieves a sort of pure and perfect state, whereas nothing else creates a perfectly symmetrical dynamic. Commercial painting attains a maximally perfect space: complete deception. This sort of completion is very difficult to attain, and it forms a stable reference system for me. I think about whether it’s possible to use a different method to reach this sort of completion. But as long as there is some significance to judge, then this sort of completion has not been attained. Thus, the things we make are all fragmented, incomplete things.

The significance of Wang Xingwei’s work lies not in his paintings per se, but in their treatment of the great construction that is painting. His paintings do not express anything by themselves. Rather, their effect, like individual go pieces, is relational. They relate to a system constituted by all paintings, ancient and modern, foreign and Chinese.

His art has inevitably influenced his contemporaries in a variety of ways, not only in northern China, and not only in the field of painting. Nor is he the only artist to respond to the diversification of art media by expanding the formal capacities of painting (Yan Lei’s paintings are another example). But to Wang Xingwei, painting is more than a medium. To him, painting has an a priori significance— this is what sets him apart. His pervasive influence can largely be attributed to his attitude toward art and his unceasing reconsiderations of form and technique. In the eyes of some young artists, his influence has transformed the concept of painting; this transformation has made it possible for young artists to participate in and contribute to contemporary Chinese culture. Certain painters with connections to Wang, including Xu Cheng, Qin Qi, Zheng Qiang and Li Wei, represent a new generation of northeastern Chinese painters with regional characteristics (of course, Qin Qi and Zheng Qiang are not northeasterners). Liao Guohe, a member of the new generation of Hunan artists, was also encouraged by Wang’s art to leave his job in television and become a painter.

Artists such as Qin Qi, Li Wei and Deng Qiang first encountered Wang Xingwei’s work at the beginning of the second stage of his artistic career. At first, these young and enthusiastic artists did not grasp his intentions, and they opposed and even ridiculed this figure who had not attended the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts and yet still dared to commit public artistic transgressions. But as they began to participate in shows and seriously consider their future as artists, they began to recognize Wang’s audacious reasoning. His affable disposition and propensity to form bonds over drinks facilitated his rapid integration into their midst. But in 2002, Wang relocated from Liaoning to Shanghai, where he became engaged in intensive exchange with the metropolis’s young video and installation artists.

The artists influenced by Wang Xingwei are quite different from one another, but they all share a grasp of the freedom and openness of painting, and have found creative methods and techniques that suit them. Xu Cheng, who is one year older than Wang, also taught for a time at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts. He graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts and studied abroad in St. Petersburg; the subversive painting style he developed during his student years deeply tallied with Wang’s approach. Xu Cheng’s subject material, cultural orientation and linkage of art to life are all representative of northeastern Chinese painting. Qin Qi developed his own multi-faceted approach to freedom. Each of his paintings brims with adventurous experimentation and self-consciously avoids maturity and differentiation of style. Though he possesses a rigorous academic background, he avoids becoming a mechanized slave of technique by instinctively taking the initiative to invest his self and his life in his work. At the same time, as a member of the younger generation of artists, Qin Qi has his own sober understanding of trends and fashions, and he is equally capable of deriving his artistic sustenance from modern and pre-modern sources. Li Wei sought his own path within the academic environment. His prolific output of paintings feature experimentation with color and visual psychology, as well as a deep grasp of imagery. Zheng Qiang, who took up residence in Beijing after moving to Shenyang from Xi’an, experiments with the connection between reality and imagery and the relationship between cognitive structures and techniques of reproduction.

Even before Liao Guohe traveled to Shanghai to seek out Wang Xingwei, his work tested and affirmed Wang’s postulations in both quantity and quality. His creative process invokes Lu Xun’s statement that “the journey of knowledge begins in confusion”: he sedulously avoids understanding, uses the most primitive of painting practices to intrude on reality, and incorporates language in his work. Thus, he heeds Wang’s call to face the great challenges and great doubts intrinsic to life.

Wang Xingwei and the artists with whom he is associated are facing a major question in contemporary Chinese culture: What is China? What has changed since Wang found Gericault in a bookstore thirty years ago? What is “contemporary,” and why is it being paraded around so much? History is just a label assigned to previous generations by later generations; Wang and his ilk are arguing that to withdraw from the historical order is to be contemporary, and perhaps it is better yet to withdraw from the contemporary as well. To be fooled by the mirage of linear history and to seek oneself in the past leads only to the loss of freedom and reality. And freedom and reality are essential to living for oneself, and to making paintings for oneself and one’s friends.