MELODRAMA AND METISSAGE: THE ART OF MING WONG

| September 1, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

A CHINESE SINGAPOREAN man in an emerald green dress looks into a mirror. He tremblingly tells his character’s black mother— here played by an Indian-Singaporean actor— “I’m white. White. White!” On a dual screen, another Indian Singaporean actor simultaneously delivers the same lines, this time to a Malay Singaporean actor playing his character’s black mother. The two sets of male actors are performing a pivotal, emotionally charged scene from Douglas Sirk’s 1959 Hollywood blockbuster Imitation of Life, in which Sarah Jane, a young American woman of mixed race descent, disowns her ailing black mother Annie.

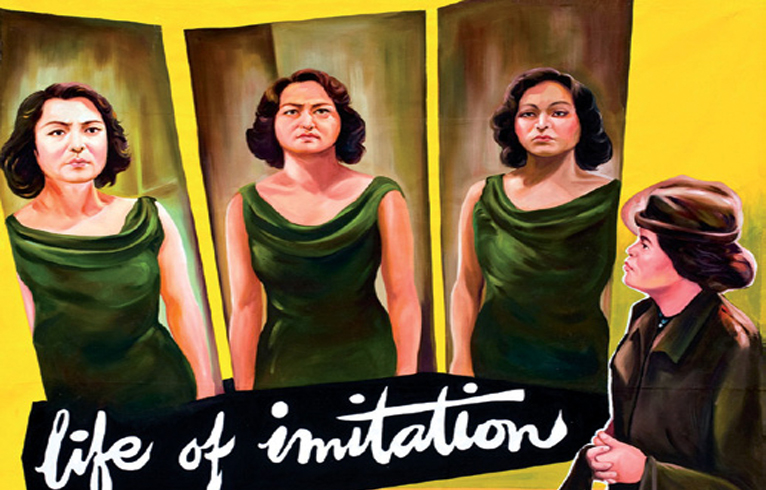

But in this iteration, the scene is a video installation by Ming Wong, recasting Sarah Jane and Annie with male actors from Singapore’s three main ethnic groups: Chinese, Malay, and Indian, making praxis of the country’s ubiquitous CMIO (Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Others) categorization system. With each shot, the actors rotate roles, further destabilizing the racial binaries otherwise ascribed to them. The men are all too old to pass for Sarah Jane and too young to pass for Annie. Dressed in cheap wigs and ill-fitting cocktail dresses, the effect is both visually preposterous and mesmerizing, sustained in equal parts by the melodrama of the original and the complete dissonance of the new.

Ming Wong describes the inversion of race, age, and gender roles as a total “miscasting,” assigning male where female is called for, substituting CMIO for black and white, inserting young for old and old for young. It’s a common tactic employed by the Berlin-based Singaporean artist, who frequently mines world cinema for source materials that he then remakes into video installations, “sweding” the original (to use the term for a slipshod remake of a popular film from Michel Gondry’s 2008 comedy Be Kind, Rewind) on his own terms. He couples the appropriation of content with breakdowns in conventional filmmaking, using a decidedly lowbudget aesthetic (cheap costuming, choppy editing, comically conspicuous green-screening) to bring the underlying racial, linguistic, and cultural valences to the forefront.

For inverting so many assumed codes of language, visual production, and identity, Ming Wong has been the subject of increasing international attention. Life of Imitation, Wong’s appropriation of the original Sirk film Imitation of Life, appeared as part of the Singapore Pavilion at the 2009 Venice Biennale, earning him a Special Mention for “Expanding Worlds.” After years without international representation, he joined the forward-thinking Vitamin Creative Space’s roster, and has received his first solo museum show this year at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, Washington— attention that has been a long time in coming.

As much as the sources for Ming Wong’s filmic works are diverse, strong autobiographical interests hold them together. Wong’s Chinese heritage and the construction of the Singaporean state loom particularly large. Born in 1971 to Cantonese-speaking Chinese parents, Wong considers his history typical of his generation: His paternal grandparents migrated to Singapore from southern China, living through Japanese occupation during World War II, with Wong born only a few years following Singapore’s subsequent independence and separation from Malaysia.

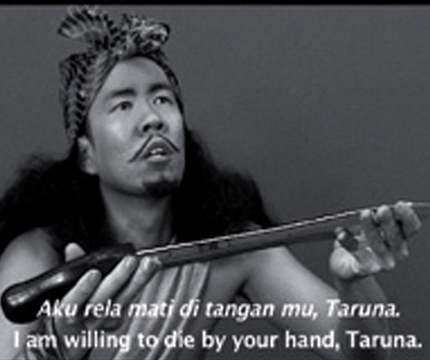

Both Life of Imitation and Four Malay Stories are clear manifestations of this history and its accompanying racial dilemmas. In the latter, Ming Wong plays sixteen different Malay characters from films by popular post-war Malay entertainer P. Ramlee; in each vignette, he re-enacts Muslim sexual taboos in condensed melodramas. Audiences familiar with P. Ramlee’s legacy recognize touchstones of Malay culture, with much of the original dialogue having entered popular culture; Wong further asks native audiences to suspend their disbelief and accept an ethnic Chinese in a host of Malay roles. Four Malay Stories and Life of Imitation make for explicit explorations of the identity politics that dominate the national discourse in Singapore, a country whose diverse ethnic composition is underscored by unresolved questions of assimilation versus recognition.

Language is another core interest for Ming Wong, who spoke Cantonese at home but learned Mandarin at Catholic school. In Love for the Mood recreates pivotal scenes from the similarly titled Wong Kar-Wai film, perhaps the one single movie recognized by foreign audiences as quintessentially Hong Kong. Wong hires a Caucasian actress to play both Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung’s roles, twisting her hair into an impressive bun when she dons Cheung’s famous cheongsams and slicking it down for Leung’s white collared shirts and slacks. But the real spectacle is her performance, delivered in Cantonese learned phonetically. In the final installation, three screens simultaneously play the same scene; the first is an early take, the actress struggling visibly with her lines. On the second screen, she is increasingly comfortable with the foreign language, and the third is her smoothest delivery of the Cantonese dialogue.

HYBRID BEGINNINGS

ORIGINALLY TRAINED IN Chinese calligraphy at Nanyang Art Academy in Singapore, Ming Wong began working in Singapore’s English-language theatre, writing the book to Chang & Eng the Musical, a dramatization of the lives of the nineteenth-century Thai-born conjoined twin brothers that inspired the term “Siamese twins.” The musical was a critical and commercial hit for Singapore, a country not particularly known for its cultural exports, and toured throughout Asia in the late 1990s, eventually becoming the first English-language musical to be performed in China.

Just as soon as he became known as the Chang & Eng guy, Wong left Singapore to study at the Slade School of Art at University College in London, completing his MFA in 1999. His graduation piece, Honeymoon in the Third Space, featured footage of a fake wedding with one groom and two brides. The groom, of Singaporean and British ancestry, marries two brides, one British and the other Asian, who switch in and out of one another’s white wedding gown and red Chinese wedding dress in each scene. Rather than reusing the tired rhetoric of a crisis between “East and West,” the film imagines the embodiment of the union between two cultures.

Following his graduation from Slade, Wong remained in London, producing more video works with distinctly theatrical qualities. Ham&cheesomelet and Whodunnit? are two emblematic works from Wong’s time in London, each questioning the stability of language and the British canon through theatrical gestures. Wong describes Ham&cheesomelet as a “scrambled Shakespeare sonnet,” filming himself in what looks like a budget William Shakespeare Halloween costume, complete with DIY frills around the neck and a paper mustache taped on. Wong attempts to deliver Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy, but mangles every line, making a mockery of the English language’s most treasured playwright while simultaneously offering up an absurdist poetic beauty to his unorthodox rearrangement of a hallowed text.

Whodunnit?, filmed in 2003 and 2004, gave Ming Wong the resources and the cast to make a more probing exploration of the same themes; this time it is the classic British murder mystery that is reimagined. With financial support from Arts Council England, Wong hired a multi-ethnic cast to portray the character types typically found in drawingroom murder mysteries, casting specifically for each ethnic category found on the Arts Council’s cultural diversity monitoring form. The cast of mostly second- or third-generation British actors delivers their lines in alternate accents: first in RP, or received pronunciation, the standard for British English; and then in the imagined foreign accent of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. By the boxes, actors of black African, black Afro-Caribbean, Asian, East Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American, Greek Cypriot, Eastern European Jewish, and Irish descent, try to take on accents they’ve never had but might have been familiar with while growing up. The power dynamics of the group circle around the police detective at the center of the group, and accent functions here as the currency of power, shifting between RP and imaginary, racialized accents to express the subject’s relation to the detective.

LONDON TO BERLIN

WHEN THE RISING cost of living cut Ming Wong’s time in London short, he moved to Berlin, a city whose cheap cost of living and dynamic expatriate community were already attracting scores of young artists, writers, and revelers. To Wong, the relocation was more than just a move; it was a sea change, and he took the transition as the autobiographical starting point for Lerne Deutsch mit Petra von Kant, a partial remake of Fassbinder’s 1972 film The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. In the original, von Kant, a thriving fashion designer, loves and loses the object of her desire. The grief of her loss peaks on her birthday, when she lies alone, raving on the floor of her bedroom, a bottle of hard liquor in hand.

Ming Wong, new to Germany and its language, recreates that scene as an alternative introduction to this new tongue. He skips over the more traditional starting points for learning a foreign language— greetings, weather, food— in favor of memorizing Petra’s anguished monologue of emotional breakdown. Surely, matters of the heart are more essential to true communication. Donning Petra’s distinctive blonde wig, neon jumper, and floral choker, Wong teaches himself to describe his own bitterness, despair, and insecurity in Petra’s words, finding a cathartic parallel between Petra’s anguish and his own self-doubt upon moving to Berlin, a selfdescribed “single, gay ethnic-minority mid-career artist” on the verge of middle-age and wash-out.

From there, it’s a familiar path to the Venice Biennale: the next year, he remade another Fassbinder classic, Angst essen Seele auf, destabilizing the racial, sexual, and linguistic pluralism of the original with Wong in every role, acting out in rough German the story of Emmi and her Ali, a middle-aged housekeeper who falls for a much younger Moroccan guest worker. Angst essen is followed by commissions for the Venice Biennale, including In Love for the Mood and Life of Imitation, the latter accompanied in the exhibition by lush billboards painted by Singapore’s last surviving billboard painter, Neo Chon Teck, in a further tribute to the times and their legacy.

VENICE AND EVERYTHING AFTER

VENICE WAS AN unqualified triumph for Ming Wong. His pavilion, which earned a Special Mention from the Biennale’s prize committee, was perhaps more importantly one of the most commonly discussed pieces in the show’s 2009 edition. Professionally validated after a long period of doubt, Wong was fêted as a hero back home in Singapore, doing good by the Ministry of Culture’s imperative to exert soft cultural power abroad. But the accolades inspired another autobiographical reckoning within Wong and his oeuvre, and while in Venice, he began filming Life and Death in Venice, based on Luchino Visconti’s 1971 film version of Thomas Mann’s canonic novel. Again, Wong plays all major roles; in this case that of the aging writer Gustav von Aschenbach and the object of his obsession, Tadzio, all while updating the context of the work to include the Venice Biennale (Wong as von Aschenbach takes in Paul Chan’s Sade for Sade’s Sake, shown in the Daniel Birnbaumcurated main exhibition “Making Worlds,” while Wong as Tadzio wanders through Zilvinas Kempinas’s TUBE in the Lithuanian Pavilion). In both the novel and Visconti’s film, von Aschenbach and Tadzio represent the polar binaries of death and youth, intellect and passion.

Sexuality had never been silent in Ming Wong’s work, filled with repeated instances of cross-dressing and sensual charge. But it had never been given its full expression. In Life and Death in Venice, however, sexuality is given its full expression, as Wong adapts a quintessentially homosexual narrative to a personally inflected context. Increasingly, location too begins to play its own role. Previously, Wong had filmed his work on relatively straightforward theatrical sets— Petra von Kant’s bedroom, a British drawing room, a 1960s Hong Kong eatery. Here, Venice itself plays as large a role as the characters who wander through it. Von Aschenbach and Tadzio hardly exchange words, their interactions are framed instead by the contemporary (the Biennale) and the hallowed (the historic Grand Hotel des Bains on the Lido, filmed just days before it was destroyed for conversion into luxury apartments). Most recently, Wong traveled to Naples, filming his own version of Teorema by Pier Paolo Pasolini. In the original, a bourgeois Italian household is shaken after an unknown visitor seduces every member of the family; in Wong’s version, he again acts out every role. Naples itself is brought to the forefront, its authenticity set in contrast with Wong’s cardboard charades.

But it is the role of melodrama that is essential to understanding Ming Wong’s works. Recent critical explorations of the form have hailed it as a form for a post-sacred era, allowing the hyperdramatization of social forces in conflict to embody the ways of being that are assumed in our lives. Melodrama “acts out,” using a dramaturgy of excess to reject the repressions, accommodations, and disappointments of the real. Wong’s films create a mesmerizing cultural imaginary that highlights otherwise latent sexual, linguistic, and racial boundaries. His Petra von Kant is an anxious solipsism but also an ironic rupture, his “sweding” of global cinema an imaginative mode that brushes against the otherwise unspoken codes that underwrite global society’s constitution.