WIM DELVOYE

| October 19, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

The artist Wim Delvoye is notorious for his penchant for depraving the human experience with either subtle or otherwise extremely crude humor. In his 1999 work Anal Kisses, he used red lipstick on hotel stationery, producing the puckering of an anus; in another 2000-2001 series he used an X-ray to record sexual activity, and unabashedly exposed the act of intercourse by naming the works with crude titles like Dick, Lick, and Suck. His most widely recognized— and most controversial— work is Cloaca, for which Delvoye manufactured a machine simulating the human digestive system: a mechanism through which food is passed and ultimately converted into actual feces, which are then vacuum-sealed as final “works” to be sold to the public at a price of USD 1000 per piece.

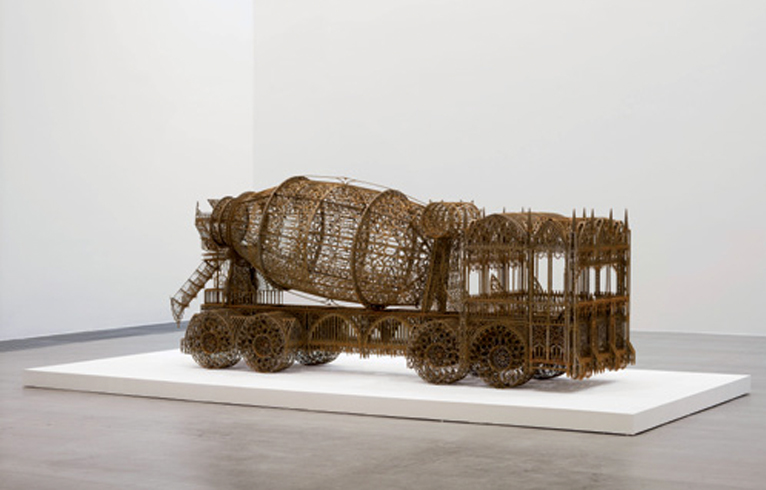

In contrast, the works selected for Delvoye’s most recent solo exhibition at Galerie Urs Meile are, visually speaking, relatively restrained— or, it could be said, conservative. The exhibition is primarily comprised of gothic sculptures, installations, and designs. The medieval Gothic style— symbolic of religious order and spiritual ardor— intimates a spiritual purity, a loftiness, and a sense of reverence and awe. This he integrates into the steel-wrought foundations of industrialized society— a space that is, conversely, most lacking in mystery and a sense of the divine— as fabricated carvings that loom amidst an air of rot and decay: the emissions of desire. The solemn, hefty forms of carefully crafted automatic dump trucks, rubber tires, and cement mixers both captivate and perplex the senses. Viewers ultimately slip into the interstice between reality and pure fabrication. These complex and intricate structures recall the gravity of the words Delvoye carved into a rock face in 2000: “OUT WALKING THE DOG. BACK SOON. TINA;” “HONEY, DON’T FORGET TO TAKE OUT THE GARBAGE. NINA.” Great pains were taken to construct these sculptures, and yet they are homages to but the most basic, frivolous categories of existence. In turn, the reverse seems to come true: the most frivolous things, when born of the pains of spiritual labor, become somehow sacred and magnificent.

In this exhibition the audience can still find content based on themes of indecency. Stained glass windows decorated with X-ray images serve as an alternative form of Church decoration. Different areas of the body are shown with varying degrees of exposure. In some, the quality is not exceptionally clear, and the way in which the light plays off of certain body parts endows them with a distinct holiness. Here, religious symbols come together with images of desire, excretion, and flesh, forming an object that seems at first glance completely decent and reasonable, but turn out to be exposing some kind of scam.

Behind a red curtain is a three-screen video installation that documents Delvoye’s experience of opening a pig farm in China, which he has used specifically to create his pigskin tattoo works. The video and the pigskin tattoos come together in a moment of mutual interpretation; the exquisiteness of the tattoos collides with the harsh reality of the process undergone to obtain the pigskins. It is a juxtaposition that sheds light upon both the aesthetic beauty that results from human desire, and the most unpleasant truths that are contained just behind it.

Milan Kundera once wrote that man is but a machine that emits foul smells. Even so, we hold onto our never-ending dreams of a romance bursting with fragrance, one that conquers all and into which we yearn to wrap our lovers. These contrived desires are woven into a brightly colored, two-headed flower whose split branches bloom out from the deepest recesses of humanity. This is the eternal paradox of the human predicament and, as far as Delvoye is concerned, what really lies at the bottom of human nature. Li Xiaonan (Translated by Katy Pinke)