A DISTANT SPIRIT OF INDEPENDENCE: THE CARTOON ART OF HUANG YAO

| December 6, 2011 | Post In LEAP 11

It is an incontestable fact that, in contemporary China, the original social and critical nature of cartooning has diminished. An exhibition of work by Huang Yao (1917-1987) at the Shanghai Art Museum earlier this year, curated by the author, showed a cartoonist working in Shanghai in the 1930s and 40s who possessed a spirit of independence, at once coolly exposing society’s ills and earnestly advocating societal revival.

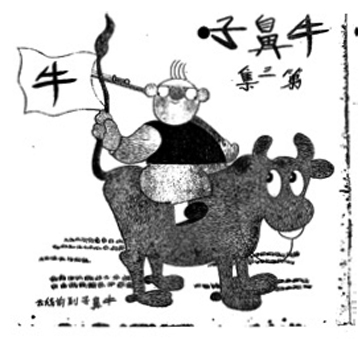

HUANG YAO’S ANCESTRAL home was Jiashan county in Zhejiang province, but he was born in Shanghai, the city where he made his name. In May 1934, at the age of 17, he began publishing his “Ox Nose” (Niubizi) series of comics in the Xinwenbao, a Shanghai daily paper at which he was employed. “Ox Nose” was a typical Chinese gentleman in a long gown and black vest, with a big round face and five small, collinear circles for his ears, eyes, and nose. He wore black cloth shoes and was ridiculously pigeon-toed. Interestingly, the shape of his face was highly similar to that of Huang’s own, and it is said that the cartoon was the result of a flash of inspiration experienced by the artist while looking in the mirror.

This was a golden age of cartooning in China. The Republican system instituted following the 1911 Revolution had gradually stabilized, and the liberating influence of the May Fourth Movement was pervasive. Western art forms were becoming popular. Shanghai was China’s commercial capital and also the center of the newspaper business. These factors combined to provide a fertile environment in which cartoon flourished. Some critics even argue that the rise of cartoon in the early years of the Republic marked the latest step in a series of epochal art forms, preceded by shi poetry in the Tang, ci verse in the Song, qu drama in the Yuan and fiction in the Ming and Qing. “Ox Nose” was born after Ye Qianyu’s “Mr. Wang” but before Zhang Leping’s “Sanmao.” These three original cartoon figures constituted a peak that, to this day, is almost unsurpassed in the history of Chinese cartoon.

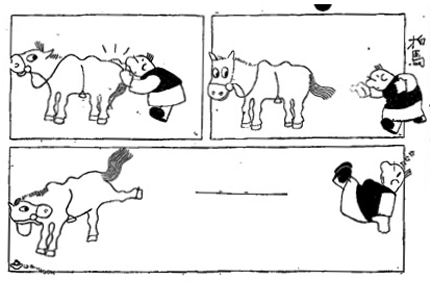

The artistic component of cartooning is different from that of many forms of drawing and painting. Due to its link to current events, cartooning has a facile and direct relationship to society. Huang Yao produced eight collections of “Ox Nose” in less than two years, and this oeuvre clearly shows that his critical attitude toward society became more and more distinct. In the first five collections, Huang employs humor to its utmost. “Ox Nose” adopts various societal roles, sometimes pedantic, sometimes pretentious, and many of the storylines are irresistibly funny. But Huang was not limited to juvenile humor. Rather, he full-heartedly voiced his opinions on society. In the first collection, in a cartoon titled “Cruel World,” “Ox Nose” is compelled by a monkey into juggling, forced by a donkey to pull a cart, ridden by a horse and hitched to a plow by an ox, suggesting a completely topsy-turvy world and expressing the artist’s heartfelt discontent. This spirit of social criticism erupts like pressurized magma in the “Blessing Collection” and the “What If Collection,” in which “Ox Nose” becomes a victim and critic of society. The target audience of these later works had shifted from children to adults. There are in fact no blessings given in the “Blessing Collection,” in which Huang draws upon folk songs and nursery rhymes to bitterly satirize the inequality, lawlessness, philistinism and hypocrisy of contemporary society.

Huang Yao’s truly independent stance as a cartoonist is praiseworthy. All of his critiques originated in his personal conclusions about society. In the “What If Collection,” the most peculiar and combative segment of the “Ox Nose” series, Huang draws on characters from Chinese cultural traditions and employs absurdity, self-deprecation, juxtaposition and other artistic means now viewed as characteristic of modernity. These marvelously imagined comics are rich in black humor and highly caustic in their exposition of the dark sides of society and humanity. “What If I Were Guan Yu,” “What If I Were Grand Duke Jiang,” “What If I Were Wu Song,” “What If I Were the Goddess of the Moon”— all of these suppositions subversively recast illustrious cultural personages in exceedingly vulgar light. The collection thus makes a profound suggestion about the insidious effects of environment: the hero is reduced to a clown, the great beauty succumbs to desire, and nobody is immune to negative influence. These discomforting what-ifs show that Huang, on the eve of the eruption of the War of Resistance, had become extremely disappointed in the objectionable habits of society and humanity, but he continued to use his pen to cry out and call for the rousing of the masses. His critical work had delved deeply into the morbid state of China’s national character.

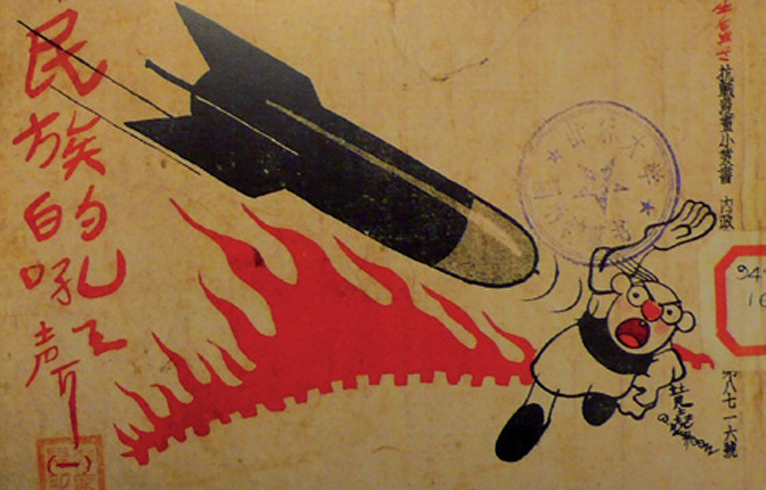

The War of Resistance changed the target of attack for cartoonists, as the survival of the nation became the most important theme. Huang Yao’s work exhibits a major transition in this period. He became one of the most ardent patriots among his contemporaries, and his work was rich. In the rear area of Chongqing, he ceaselessly produced rousing war cartoons, and “Ox Nose” was transformed into an outraged Chines partisan. He was the first and likely the only cartoonist to produce a cartoon illustration of March of the Volunteers, the Chinese national anthem. But before long, his righteous disposition returned to his work— he could not resist criticizing various unpleasant phenomena in the rear areas in a series of captioned folk paintings. This sort of remonstrance was rare among cartoonists during the war years. He drew the rats of Chongqing, suggesting the “scurrying about in the night” of collaborators. He drew Sichuan-style sedan chairs, calling upon “those seated in sedan chairs: do not forget the 70 million compatriots in the Northeast and the 50 million compatriots in the Southeast who are sitting on pins and needles!” He traveled deep into the Southwestern hinterland in order to capture the state of wartime China. In “Cartoon Chongqing” and “Cartoon Guiyang,” he laudably included representations of China’s ethnic minorities in his direct, rich and reliable visual portrayals of the conditions of wartime existence endured by people in the rear areas. These works held deeper significance; in the words of Graham Peck, then the director of the Information Bureau at the U.S. Embassy, Huang’s folk cartoons captured “that happy tenacity and endless potential of the Chinese people.” In the nearly 70 years that have passed, these Southwestern folk cartoons have become prominent in folklore studies.

The exhibition of Huang Yao’s art at the Shanghai Art Museum has drawn high acclaim from critics and cartoonists. Following the conclusion of the War of Resistance, Huang traveled to the Indonesian archipelago and ultimately took up residence in Malaysia, so his substantial accomplishments during both the flourishing Republican era and the anti-Japanese resistance have remained relatively unknown. However, brushing the dust off of his “Ox Nose” series reveals a truly brilliant body of work. The most thought-provoking element represented in Huang’s work is the spirit of freedom and independence enjoyed by cartoonists of that era. Huang inherited the traditions of the late Qing denunciation novels and joined progressive writers such as Lu Xun in adopting a stance critical of society. This stance was the soul and distinguishing characteristic of cartooning, and is also exactly what is missing from Chinese cartoons today. Cartoons can be funny, ridiculous, realistic or indulgent, but their strength nearly always lies in their power to recognize and comment incisively on society. The value of Huang’s cartoons goes beyond his position in the social vanguard, lying instead in his wisdom and integrity as an intellectual, perceptive of society’s morbidities and duty-bound to reveal them to the masses. The context and material of these cartoons is buried in the past, but their spirit of independence and insight into society is timeless. In this sense, Huang’s cartoons and this exhibition should lead contemporary Chinese cartoonists to reflect on the prospects for radical change. Of course, the weakness of contemporary Chinese cartoon is the result of the objective environment; the cartoonists themselves cannot be blamed for everything. The lesson here is that being a cartoonist requires elite insight into society and culture; this is the cornerstone of the spirit of independence.

After relocating to Malaysia, Huang Yao turned his artistic attentions to calligraphy and traditional Chinese painting. His parents had steeped him in cultural traditions, and he had a strong background in Chinese history, classical prose, calligraphy, painting and even folktales and stele rubbing. He drew on traditional Chinese culture for his subject material and created a unique “emerging from the clouds script,” as well as character paintings, and more. He escaped the cross-strait, bifurcated Chinese political system in 1949 and turned his unrecognized talents to the exploration and reinvention of traditional Chinese culture. How much brilliance, what kind of art, and what sort of legacy in Chinese culture lies in the work produced by this Chinese renaissance man who escaped from the path of history— these are undoubtedly questions of rare research value. Of course, that is a topic for another article.