LU LEI: FLOATING ICE BIOGRAPHY

| February 15, 2012 | Post In LEAP 12

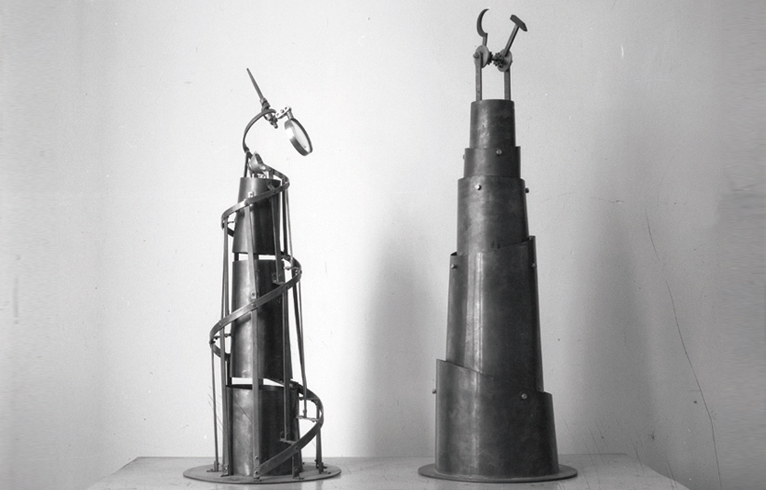

Lu Lei’s works possess an intricacy of form beckoning association with the Baroque style; invocative of the sublime and the spiritual, they are as rich with imagination and movement as they are echoing with a sort of hallowed purity. In his newest solo exhibition “Floating Ice Biography,” Lu selects to utilize materials and ideas that are either in the midst of disappearing or have already faded into obscurity: monument towers, Morse code signal lamps, assembly halls adorned with sculptures of Mao Zedong, the mapped layouts of Cold War socialist barracks. Altering their original functions and structures, Lu models an illusory alternate reality based on the memories and deceptions of a bygone era— those fragments left behind by history— at one time existing in such precise terms but now eroded by the passage of time into mere “specimens”— little half-truths floating like last lumps of unmelted ice below the water’s surface. In this illusory world, we find what appears to be a highly measured form of revolutionary romanticism.

“Floating Ice Biography” exhibits a portion of Lu Lei’s output since 2008, including multimedia installations and watercolor paintings, the latter serving as design drafts for the former and with a degree of meticulous detail that rivals that of actual architectural blue-prints. In their completed form, these drafts provide technical support for the ultimate realization of the installations, just as they are seen in the exhibition hall: metal, glass, water pumps and refrigeration equipment— sturdy, solid combinations of industrial materials reminiscent of the machine models one might find in a laboratory. Clearly, the explicit reciprocal relationship between the paintings and installations demonstrates the progression of the artist’s work; the specific order of this sequence produces the effect of an on-site workshop, inviting the audience to enter the very narrative the artist has constructed through his works.

Only a portion of the works from the “Floating Ice Biography” series is on display, but what is shown leaves us with a sense of the series’ overall direction: an extraction and re-creation of a unique moment in this nation’s history. It would seem that at every turn the exhibition sheds new light on the fanatical Utopian pursuits of mid-century Chinese communism. In reality, Lu Lei— born in the early 1970s— possesses no first-hand experience of that period; even those childhood memories he does possess are inaccurate. Thus his framework for discussion resides not at the sociopolitical level, but at the level of language and expression.

All countries in the early stages of socialism share similarities in artistic style: the abuse of symbolism, dependence on macro-narratives, and fascination with large-scale production. Behind these streamlined modes of expression is the operation of a unitary system of values and political culture. But when these modes of expression emerge here, they undergo a seamless transformation into an individual’s account of his personal confrontation with ideological rhetoric. These works— in their reimagining of history— expose conflict and bewilderment in their rawest forms. The precarious view from The Tower in the End, bats circling unceasingly around an assembly hall portrait of Mao Zedong, a spring of water flowing from a heart, crows flying about in an abstraction of a park: are these just fictional scenes produced for dramatic effect, or are our actual, beautiful memories of the past themselves this absurd and disloyal?

This question raises an issue of even more profound significance: the modification of historical value is not a phenomenon limited to the realm of political motives. In reality, a similar means of modification has already been accepted and adopted by the whole of society. Almost all of us have been drawn in by a spiritually and emotionally idealized past. Our political culture’s alteration of reality is far from an isolated phenomenon; it is founded in a deep-reaching mass cultural psychology. Zhang Xiyuan (Translated by Katy Pinke)