SHANGHAI ABSTRACT: PARADIGM OF CHINESE CONTEMPORARY ART

| February 1, 2012 | Post In LEAP 12

Shanghai has been a model region for the practice of abstract art in contemporary China. Over the past 10 years, amidst the overall pattern of Chinese contemporary art, abstract art has come to be one of Shanghai’s emblematic features, one of its stronger cultural calling cards.

TRACING BACK IN HISTORY

SINCE THE MING and Qing, the inclinations of the literati have dominated the culture of southern China, which has always venerated inherent qualities of refinement, conciseness, and tranquility in character and temperament. Taking Kunquopera, the gardens of Suzhou, and Ming-style furniture as well as Yixing red clay teapots as representative of a certain aesthetic temperament, this style has continued to influence literary and artistic production, helping establish the historical superiority of southern Chinese culture. These sorts of human origins inculcated southern Chinese culture with the quality of meticulous attention to detail, and passed on the skill of paying particular attention to form. As homegrown artists here say, these precepts are part of their flesh and bones, built into their fundamental nature.

One of the earliest port cities in China’s modern history, Shanghai’s identity as a former colony has necessarily influenced its local cultural and artistic development. After the May Fourth Movement, northern Chinese culture began to see both debate over and practice of various Eastern and Western doctrines. By comparison, such debates were relatively few in Shanghai. The cultural backdrop of colonialism caused Shanghai’s inherent character to become more pragmatic, and the preponderance of areas where Western influence had crept eastward also caused the pace of the spread of outside information to rapidly increase. Artistic practice in Shanghai also adjusted along the lines of international trends. China’s first art institute, first instance of life sketching, first modern art society, and first national art exhibition all took place in this Western-influenced, rising metropolis.

In 1931, the Storm Society (juelan she) was established in Shanghai. Its primary members Pang Xunqin, Ni Yide, and others devoted themselves to an experiment in “art for art’s sake,” in opposition to naturalism and realism. They advocated art’s ontological purity in the independence of the art form. Even though they still had not created any purely abstract works, they had already put forth the notion of the supremacy of form, establishing a very particular and exceptional value orientation in the history of Chinese modern art. In 1934 in Shanghai, Lu Xun proposed what he famously described as “sharism,” advocating the New Woodcut Movement. From that point on, the new climate of literature and art in China became standard. At that time, Shanghai’s modern broadcast media system was the most developed throughout all of Asia, and it included newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts, film and other such industries. A new urban class driven by Westernized education arose, among which forward-leaning international literary and artistic thought was prevalent. This gave rise first to a kind of resignation, then to an aesthetic sensibility that strove for change. Additionally, literary and cultural elites from all over the country converged on Shanghai in an unprecedented manner, suffusing this international metropolis with creative spirit and artistic appeal.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War suddenly broke out, the course of Chinese modern art changed abruptly. Experimental formalism’s path of development was completely disrupted, and the entire art community switched gears toward mobilization and propaganda for the national cause. Realism became an indispensable technique, and purely artistic endeavors were denounced as untimely frivolities, effete and sentimental.

Following the victory in that war, internecine warfare between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communist Party continued, along with the political activities preceding the founding of the new Chinese state, and the entire art community was required to keep pace with political developments. After 1949, literalism gradually gained traction, later giving way to a pre-Soviet style of socialist realism. Mobilizing and educating the public and propagandizing and exalting the aims of Party leadership were the primary literary and artistic options at that time, and in fact many of the artists who made the greatest contributions to the exploration of artistic form and language were oppressed and persecuted. Examples of artists who met such fates were Wu Dayu, Lin Fengmian, Guan Liang, Zhou Bichu and others.

Worth noting is that among those of the same generation, Wu Dayu can be considered both pioneer and underlying force of Chinese modern art during the Cultural Revolution. Unbeknownst to the public, he created an underground series of abstract expressionist works. Even though these works were fairly heavy-handed in their symbolism and cannot really be said to be purely abstract, Wu worked hard to set a unique and meaningful example for later Shanghai artists to follow. From the Republic of China to the Cultural Revolution, due to the limitations imposed by the general tide of events, the official emergence of pure abstract art in Shanghai was inhibited and delayed.

THE 1980s: THE FIRST SIGNS OF ABSTRACT ART

POST-1979, AFTER years of the domestic art community following the issue of formal beauty with keen interest and the escalation of continuous discussion, Shanghai’s modern art scene gradually began to recuperate. Artists who had formerly gone underground with individual endeavors began re-surfacing, emerging one after the other. The whole of the 1980s can be seen as Shanghai modern art’s golden age of rapid development. It was also a breakout period for abstract art, precisely when many artists who later became representative figures in the art world found their personal style through the enlightenment and nurturing atmosphere of the period. It should be noted that Shanghai has always lagged in subject-oriented practice, while formal exploration, in a way, has always remained slightly ahead.

In 1979 the Children’s Palace in Huangpu hosted “Painting Exhibition of 12 Chinese Artists.” Impressionism and expressionism were the main emphasis, once again bringing the ontology of the language of artistic expression to the forefront. In 1983, “Experimental Exhibition of 83 Phases of Painting” opened at Fudan University, marking initial success for Shanghai’s abstract artists. In 1984, the distinctly appealing abstract sculptural work Drinking Water Bear by Shanghai’s Yang Dongbai won the grand prize at the sixth National Fine Arts Exhibition. In 1985, Fudan again hosted “A Joint Exhibition of 6 Modern Painters,” among whom were Yu Youhan, who had already developed his own personal style in the early1980s, and his students Ding Yi and Qin Yifeng, who became representative figures of Shanghai’s abstract art.¹

Throughout the 1980s, explorations in abstraction in Shanghai were swept up by the countrywide ’85 New Wave. A large number of young and middle-aged artists assumed avant-garde and vanguard postures, engaging in abstract experimentation. Even though most of the works they produced were fairly amateurish and crude, there were a few works that occupied a place between abstraction and poetics. But these works fully revealed the courage and conviction of the artists’ stylistic break with realism. The principle figures who emerged during that period were Yu Youhan, Li Shan, Zhang Jianjun, Zhou Changjiang, Chen Chuangluo, Miao Pengfei, Qiu Deshu, Dai Hengyang, Wang Jieyin, Cha Guojun, Chen Zhen, Hu Xiangcheng, Liu Yaping, Xu Longsen, Yu Jiyong, and others. Among them, Yu Youhan’s “Circle” series, Li Shan’s “Beginnings” and “Expand, Extend” series, Zhang Jianjun’s “To Have” and “Have Not” series, as well as Zhou Changjiang’s “Complement” series were all major works representative of Shanghai’s abstract art scene. In 1989, Zhou Changjiang’s abstract work won the silver medal at the Seventh National Exhibition of Fine Arts, marking a milestone in the course of abstract art for Shanghai and even all of China.

THE 1990s: RAPID ASCENT

THE SHANGHAI ABSTRACT art scene was quiet from the fall of 1989 up to the spring of 1992. There were almost no shows, there was no market for the art, and there was no exchange with the outside world. Opportunities to appear in domestic publications were extremely scarce. But in reality, despite the apparent stillness, it was precisely during this particular era of apparent dormancy that many artists matured and cemented their personal styles. In 1993, for the first time Mainland Chinese artists were chosen for the Venice Biennale, marking yet another milestone in the history of Chinese modern art. At that time, among the 14 artists who were invited, only one did abstract art, and that was the Shanghai artist Ding Yi. That same year, his abstract work was also selected for the exhibition “Chinese Avant-Garde Art” hosted by Berlin’s House of World Culture as well as for the First Asia-Pacific Triennial in Brisbane.

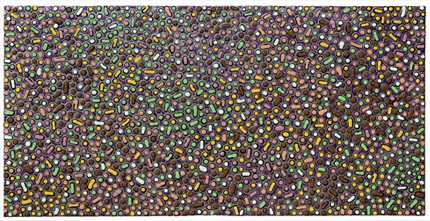

Ding Yi’s accomplishments may actually reflect the entire period of the 1980s. At that time he was already absorbed in experimenting with purely abstract art. The degree of purity of his language and his ability to discover and represent the depths of the visual sense were astonishing. In 1989, he also participated in the “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition at the National Art Museum of China. In 1994, Ding participated at an exhibition hosted by the Shanghai Art Museum. This was the first exhibition by a Shanghai abstract artist at a government sponsored event, which served to establish trust among many other artists for such events.

In fact, Ding Yi was by no means unique in his inclination towards and orientation with Shanghai. Among those from the same generation were Shen Fan, Qin Yifeng, Chen Xinmao, Song Haidong, Yu Hong, Ruan Jie, Shen Haopeng, Zhao Baokang, Pan Wei, Gong Jianqing, Chen Qiang, Qu Fengguo, Huang Yuanqing, Li Lei, Wang Nanming, WangYuan, Tan Genxiong, Song Xiaofeng, Lu Yunhua and numerous others.

The 1990s could be seen as the real debut of Shanghai abstract art. The many years of quiet development and asceticism let many artists really take off, and the special character of the city further caused the artists who lived there to have very high demands in terms of originality of form and the degree of execution in a work. Shanghai abstract art completely incorporated its distinctive aesthetic features of delicacy, inner restraint, calmness, and lucidity with the cultural connotations and fashionable sensibilities for which the city was known during that period.

In January 1996, the Fine Art College of Shanghai University Gallery presented “The Existence of the Intangible—An Exhibition of Shanghai Abstract Art” to the public, featuring 20 works of local abstract artists. This first large-scale joint exhibition of pure abstract art in Shanghai also brought together for the first time numerous abstract artists who had spent years quietly pursuing their craft. At a symposium following the show’s opening, all of those artists, who had previously navigated their artistic endeavors and careers alone, experienced a meeting of minds and a special sense of community. The successive selection of Ding Yi and Zhou Changjiang in1996 and Qu Fengguo in 2000 for the Shanghai Biennale signified the genuine acceptance of abstract art by the system.

A NEW CENTURY: THE CAPITAL OF ABSTRACT ART

AS THE OPENING of Line 1 of the Shanghai subway in 1997 symbolized, the final phase of Shanghai’s urban renewal in the 1990s was basically complete. The transformation in the city’s appearance was extremely swift and almost violent, to the extent that a new map of the city had to be printed just about every six months. Foreign capital flowed into the city, and a highly developed system of commerce brought more and more visual stimuli to the city. There were oversized shopping centers and large numbers of hotels and office buildings. Huge advertising posters and neon lights could be seen everywhere, and the incessant noise of various broadcast media was just as ubiquitous. This atmosphere provided the artists who lived in this city with an amazing surplus of images. Affected by aphasia of figurative representation, a portion of these artists turned inwards to their own heart, towards expression of spiritual leaning, forming an important reason for the exceptional way that abstract art flourished in Shanghai.

In each 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2005, the Shanghai Art museum hosted large-scale, metaphysical-themed abstract art exhibitions. Initially only local artists participated in the exhibitions, and later they expanded to include artists from around the country and then even the overseas Chinese art community, with the works exhibited ranging from paintings, sculpture, and installations to even video and performance art. The academic aim of the exhibitions was to expand the power of abstract art’s discourse to include all explorations of abstract aesthetics among Chinese people, coordinating the exhibitions with seminars and a series of publications aimed at the public. These served a galvanizing function, setting a positive example for the development of abstract art nationwide.²

The structure of Shanghai’s abstract art scene heading into the new century had already matured compared to the 1980s, having entered a stable trajectory. Shanghai’s abstract artists and critics regularly accepted invitations from home and abroad to participate in various types of academic exchange. Solo and group exhibitions of abstract art continuously cropped up at art museums, galleries and other art spaces. Galleries specializing in abstract art and dedicated auctions began testing the waters in Shanghai and achieved early success.

From the mid-1990s onward, apart from the author, many individuals have been active in theoretical research on abstract art as well as in exhibition planning, including Li Xiaofeng, Li Lei, Gong Yunbiao, Wu Liang, Zhao Chuan, Wu Chenrong, Xu Demin, Lorenz Heibling, Davide Quadrio, and others. This tiny, limited community has made a decisive contribution to the mainstream art world’s acceptance of abstract art as well as to its becoming an important symbol of contemporary Shanghai culture.

Today, Shanghai has become a beloved hub for exchange among abstract artists. Among those Chinese artists who come from all over the country as well as abroad are Zao Wouki, Chu Teh-chun, Xiao Qin, Chen Zhengxiong, Jiang Dahai,Su Xiaobai, Liang Quan and others. The number of those who have successfully held individual shows and participated in Shanghai’s abstract group exhibitions and activities is even larger. Today, even the main entrance hall of the Shanghai Grand Theater’s huge mural displays a commissioned work by Chu Teh-chun. Judging from the number of artists, the frequency of events hosted, and the influence that abstract art enjoys on society, it is clear that Shanghai has become China’s capital of abstract art.

1 In 1986, shows related to abstract art flourished. Important events included the Shanghai Museum of Art’s “First Shanghai Youth Grand Fine Arts Exhibition” and “Painting Exhibition of the Newly Completed Wing of the Shanghai Art Museum”; the Xuhui Cultural Center’s “Black and White Painting Exhibition” and “86 Concave-Convex Exhibition”; Shanghai Art Gallery’s “Sea Horizon: A Joint Exhibition of 86 Paintings”; and the Shanghai Theater Academy’s “Exhibition I,” among others. From 1987 to 1989, the unceasing exploration of abstract art was gaining momentum. Among the main events during this period that featured abstract works were: “Shanghai Painting: Chinese Art in Transformation” (1987, Hong Kong Arts Centre), “First Exhibition of Chinese Oil Painting”(1987, Shanghai Art Museum), “Exhibition of Today’s Art” (1988,Shanghai Art Museum), and so on.

2 In 2002, “An Abstract New World: Group Exhibition of Shanghai Abstract Artists ” hosted by Liu Haisu Art Museum featured abstract works of 33 artists. In 2004 and 2006, the Mingyuan Arts Center in Shanghai successively hosted two exhibitions titled “Grand Exhibition of Shanghai Abstract Art,” presenting the lives of Chinese and foreign abstract artists in Shanghai on an unprecedented scale, using abstract exploration to expand abstract art’s socialization and establish a completely new platform. In 2007, “Lines: Abstract Chinese Art” opened at Su He Art Center. In 2011, “The Tao of Nature: Chinese Abstract Art Exhibition” was presented at Shanghai’s Museum of Contemporary Art.These exhibitions represent a basic lineup of the comprehensive development of Chinese abstract art, while the possibilities for the aesthetic of Chinese abstract art continue to expand.