ART AS DIPLOMACY

| June 8, 2012

ARTISTIC PHARMACOLOGY

At last year’s Venice Biennale, five Chinese artists set out to represent their country through the olfactory. Visitors to the state-sponsored China Pavilion were confronted with a country abstracted into tea, baijiu, lotus, medicinal herbs, and incense. Even by the standards of contemporary art’s very own Olympics, this reliance on cultural signifiers was unusually strained and overwhelming.

In an interview with LEAP pre-vernissage, the show’s curator, philosophy professor Peng Feng, explained his rationale by invoking Arthur Danto: “Danto’s theory is akin to theories of traditional Chinese medicine. Art today is like a Chinese medicine shop, in each drawer there is a kind of medicine, and each kind is akin to some art form from history. Artists today don’t make new drawers and put in new kinds of medicine. They take different kinds of old medicine out of existing drawers, and mix them together to create ‘new’ medicine.”

Particularly in China, where the genesis of contemporary art history emerges only a few decades back, Peng’s analogy possesses surprising resonance. Of course, Chinese art’s medicine cabinet was not empty in the absolute, but enough drawers were that each encounter with Western art and culture was a pharmacist’s dream. Just as fast as the national economy forged ahead, so did the creation of new medicines.

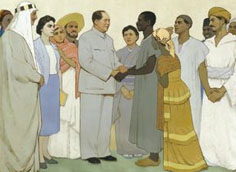

Taking a continued flurry of attention to China’s official thrust for “soft power” as its cue, this issue of LEAP offers an alchemic consideration of the forms art diplomacy and exchange have taken over recent years. Sometimes, cultural interaction has proved to be just the right prescription; at others, it has proved to be just prescriptive.

A FUNCTIONAL INSTRUMENT: CULTURE AS POWER

In the past years, the attention paid by Western media to recent changes in official cultural policy in China, particularly that which aspires to fortify national reserves of “soft power,” has been curiously scrupulous. Like most reportage on China, the majority of these stories lure the reader into politicized arguments, and rarely delve into the tangible results of the directives in question. Here, LEAP attempts to unravel the threads that tie the creation, exhibition, and acquisition of Chinese contemporary art to the powers that be, and see where they lead.

CULTURE SHOCK: AMERICAN PAINTING IN CHINA, 1981

In 1913, the Armory Show in New York introduced “modern” European art to the United States for the first time in a major way, with emphasis on the Cubists and the Fauves; no American artist could ignore what he or she saw. This found a parallel moment in 1981, when the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (BFA) introduced original American painting and “modern” art to China, which highlighted Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting; no Chinese artist could ignore what he or she saw.

THE FOREIGN SALONS OF BEIJING

Geremie Barmé reflects on a kind of unofficial international cultural exchange; a new-era phenomenon of foreign culture. These gatherings of Chinese and foreign personages have become known as foreign salons. The first generation of Chinese to participate in foreign salons indulged in political rants; the second generation are more concerned with cultural trends. To foreign participants, these salons offer not only entertainment, but also an extraordinary insight into the Chinese experience.

WHEN ART HAPPENED

In the 1990s, there were very few places to hold contemporary art exhibitions, concerts, or even simple gatherings of friends. Nonetheless, some of China’s most celebrated cultural figures would manage to break their own ground. The artist Xing Danwen acted as a visual intermediary, code switching between artist, photojournalist. and participant.