ARCHIVAL EVENT AND ITS INTERMEDIARY

| May 22, 2013 | Post In LEAP 20

Special acknowledgement to The Chabet Archive at Asia Art Archive for making the material accessible

OFTEN REFERRED TO as the pioneer of conceptualism in the Philippines, Roberto Chabet (b. 1937, Manila) is known for his cerebral, elusive compositions of readymades and everyday materials to include mirrors, plywood, neon lights, drawings, rubber tires, indigenous wood, maps, strings, envelopes, paper, and so on. Chabet’s play on form and meaning, process-oriented, anti-monumental practices appear as “an alternative to representational modes of painting and sculpture often aligned with ideological struggles during the imperial occupation and dictatorship in twentieth-century Philippines” (1). Admittedly, the above is an expedient depiction of any artist whose art practice spans half a century— not to mention in the case of Chabet, whose standing in Filipino conceptual art is not uncontentious. As researcher of the project, Ringo Bunoan— herself also an artist and a student of Chabet’s— argues, “[in] order to understand his paradoxical conceptualism, one must review art history and begin with the breakthroughs of the early twentieth-century European avant-gardes such as Duchamp and Malevich instead of the language-based propositions of the Americans in the 70s. […] Conceptualism in Chabet’s case is not simply a style, a movement or period in art history, rather it is a form of consciousness, an awareness of what art can be apart from what we can see” (2).

Initiated in 2008, the Asia Art Archive (AAA) partnered with Manila-based Lopez Memorial Museum on an archival project to compile and digitize primary materials on Chabet “as one of multiple entry points into the complicated discourse of modernity and contemporaneity in the Philippines” (3). Multiple sets of digital records are produced and kept by respective parties upon the completion of the project.

The Chabet Archive, part of which has been recently made available for public access on the AAA website, is divided into five troves of dossiers: 1) Chabet’s artistic production dating back as early as to a student work in 1959; 2) His time as founding Museum Director of the Cultural Center of the Philippines; 3) Shop 6, a short-lived yet momentous art initiative led by Chabet and fellow artists; 4) University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts, where he has taught for over 30 years; 5) A collaborative, conceptual project on a fictional artist named Angel Flores. Currently with 8,000 records, the Archive charts an uneven constellation of documents in accordance with the contingencies of material availability, though Chabet’s multiple roles as artist, teacher, and curator are pertinently revealed. The notion of archival event is deployed to describe the archive as an active, regulatory discursive system. In a widely-cited rumination on archive by Michel Foucault, it poetically portrays how an archive is the system that regulates how history/knowledge is articulated, understood, and remembered: “The archive is the first law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements of unique events. But the archive is also that which determines that all these things said do not accumulate endlessly in an amorphous mass, nor are they inscribed in an unbroken linearity, nor do they disappear at the mercy of chance external accidents; but they are grouped together in distinct figures, composed together in accordance with multiple relations, maintained or blurred in accordance with specific regularities; that which determines that they do not withdraw at the same pace in time, but shine, as it were, like stars, some that seem close to us shin- ing brightly from far off, while others that are in fact close to us are already growing pale” (4).

Among the digitized records in the Chabet Archive, which include interviews, notes and manuscripts, letters, sketches, catalogues, brochures, invitations, videos, photos, and clip- pings, the photo of a figurative work dated 1959 marks the earliest document in the collection. The work was brought to Bunoan in 2009 by its owner, Raymond See, a collector who responded to the call for material campaign, to which various artists, friends, collectors, galleries, museums, and other institutions have deposited their materials for digitization, granting the collection the potential to be envisioned as a community archive.

The work was listed in the catalogue of Salcedo Auctions (March 2012) as Untitled (Sitting Figure with Plants), whereas it was named Lost Boy in the conversation between See and Chabet, who authenticated it some years back. Bunoan explained, “Raymond See has died recently and the family put up his collection for sale. Raymond bought the work in a shop on Mabini Street in Manila. The original owner, a classmate of Chabet in college, left the country and his collection was also sold off.” This work is signed “Rodriguez.” Chabet only started to use “Chabet” when he had his first solo exhibition at the Luz Gallery (owned by artist Arturo Luz) in 1961, the year of his graduation. “Chabet says that when Luz found out he had an ‘exotic’ middle name, he advised him to use it instead, plus there were already other artists named ‘Rodriguez’ at that time. Chabet also thinks his mother is the artist in the family (she plays the piano) and he also wanted some distance from the politics associated with the Rodriguez family (his grandfather was a statesman and mayor of Manila)” (6).

All in all, pulling together such anecdotes from various sources is not unlike scavenging. Yet, how do these anecdotes contribute to the historical discourses? What other questions are invoked from these threads? How important is this (rare) figurative work dated 1959, when Chabet was still just a student in the architecture department at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila? Who determines its significance? How does it reflect Chabet’s architectural training, which may or may not have informed his later practices? What does it tell us about the art market in terms of the changing hands of an artwork? From Lost Boy to Untitled, what is the market concern for selling this, a figurative work by a “conceptual” artist? How does the unfolding of Chabet’s political family background help us to understand his antiestablishment stance? What is the latent intertextuality among the records in the collection?

Working assiduously and closely with Chabet and other donors to annotate the collected materials forms an essential part of the archival event. Bunoan also earnestly deliberates on unorthodox archival strategies that foreground subjective knowledge and fragmented memory. In contrast with traditional methods of academic historiography, Bunoan takes on the advantage of exhibition, its performativity, as experiment of archiving. Titled “Archiving Roberto Chabet,” Bunoan (re)mounted a number of artworks “to work within the cracks in the narrative, re-constructing and presenting some of Chabet’s works, which have never been realized or those that have escaped documentation. In doing so, she not only creates different vantage points for looking into Chabet’s work but also opens up varying levels in the way we remember” (7).

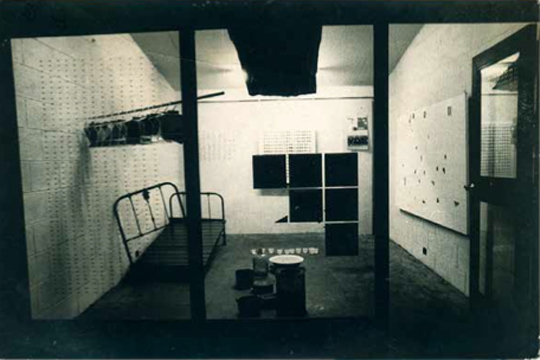

Incorporating the tactic used by Chabet in the 1974 Bakawan exhibition, Bunoan has installed, in this 2009 exhibition, the works behind a closed glass door, which “sets limits for the viewer and prescribes a particular perspective; but more importantly, it is a portal to Chabet’s notion of a ‘no place,’ an ‘elsewhere’” (8). Intriguingly, isn’t that intermediate space between “no place” and “elsewhere” an apt dwelling of archiving?

Notes

1. http://www.newmuseum.org/blog/view/ archiving-roberto-chabet. Accessed 18 February 2013

2. Ringo Bunoan, “Seeing and Unseeing: The Works of Roberto Chabet.” Unpublished

3. http://www.aaa.org.hk/Collection/ SpecialCollections/Details/4. Accessed 25 February 2013 (Emphasis authoris)

4. Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith (New York, 1972), 129

5. Email correspondence between Ringo Bunoan and the author, dated 22 February 2013

6. Ibid.

7. http://bigskymind.multiply.com/photos/album/32/Archiving-Roberto-Chabet-2009. Accessed 25 February 2013

8. Ibid.