HU YUN: OUR ANCESTORS

| May 10, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

Curated by Biljana Ciric, the series “Alternatives to Ritual” takes the idea of artists’ museums from Documenta 5 as its departure point. Six artists were invited to show their works throughout the Goethe-Institut offices as a group exhibition. Each artist also takes turns exhibiting a solo project in the public Open Space. Additionally, special events and discussions occur all throughout each exhibition’s six-month duration. For November, it was Hu Yun’s turn.

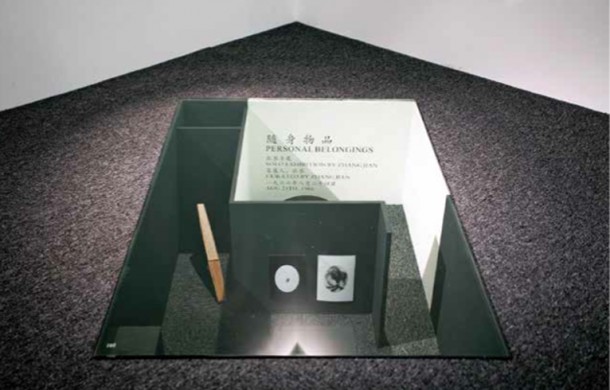

Embedded into the floor of Open Space are contents of Hu Yun’s installation of “personal belongings”— a formal hat, eyeglasses, and a folding fan. Using Berlin’s monument to destroyed artifacts as a reference, the glass-covered underground space serves as a simulated burial chamber for Zhang Jian (1853-1926), founder of China’s first private museum. In another part of the gallery, Hu uses found objects, documents, and photographs to illustrate the very long life of a man born in Shanghai in 1926 who continues to live in the city. There are his old photographs, news magazines he has collected over the years, the ideas he had learned at sishu private school. His experiences are typical of the time and similar to those of many of his contemporaries. In the photographs, we always see him from the back. When a creative and capable person passes away, someone else immediately arrives in the world. Now this man, too, has grown old, and the world keeps on changing. In the subway, everyone stares down at their smart phones, walking by a professional act lip-synching to pre-recorded songs who pretend to be beggars.

In the passageway that connects the two sections of the exhibition, a slide projector displays photographs of Hu Yun himself. Although most people do not notice the projector, the projections are nevertheless cast onto each visitor who walks past. The meaning of this installation, Untitled, is “I am always there to welcome you, even though you don’t notice me.” Yet it also reveals an existential anxiety. Hu realizes that despite his efforts to examine and research, his actions seem to have no connection with those events from the past. It is just as people may feel that their choices and work have significance, but this feeling can suddenly disappear. Here Hu acknowledges the fact that individuals and environments mutually influence each other. He is reflecting on and rethinking about exhibitions in the current art system.

Almost everybody has tired of irresponsible terms such as “possibility” and “brief analysis.” Like bad checks, they promise much but fulfill nothing. Fortunately, Hu has always had a practical attitude. When people complained about lack of a critical environment and media, he actually rounded up a few friends and started the digital magazine PDF. In this exhibition, he is not only asking question, but using the exhibition itself to give clues for finding a solution, which is to say that it is only through understanding the past can we understand the present, and only then imagine the future. This way of thinking comes from ontogeny, to study a unity and its complete cultural experience, not just its life in the present. People need to connect to the world outside of their selves and to the past; only then can they experience a true sense of existence. These are the same questions that someone who wakes up from a coma, or a character who has traveled through space in a science fiction story, would ask: Where am I? What time is it? What happened?

This exhibition seems fueled by a determined ambition to understand the present, to dissipate a grayness that would force people to lose all opportunities for a future. The thinking goes: If I can reason it out clearly, then perhaps I will find the path to lifting my doubts. (And isn’t this idea shared by most of the artist’s contemporaries?) (Translated by JiaJing Liu)