PARALLEL FAR EAST WORLDS

| May 10, 2013 | Post In LEAP 19

As curator Kaneshima Takahiro stated in his preface, the exhibition “Parallel Worlds” presents a way to understand the world from the viewpoint of plurality. The concept of plurality here refers to a process of knowledge generation, which is based on reflection and introspection, of modernity and the subsequent reality of homogenization. Thus, the plurality underpinning this exhibition of works by Japanese artists living in different Asian countries— China, South Korea, and North Korea— is not only spatial but also internal, revealing the diversity of each artist’s inner world. The world created by an artist is both dependent upon and independent from the real world; rather, it is an internal parallel.

Working within limitations of the venue, Kaneshima Takahiro separated the works into three groups, each displayed on an entire floor at A4. On the first floor are works by Watanabe Go and SHIMURAbros, which focus on the relationship between technologies and visual perception. On the second floor are works by Miki Taira and Murayama Ruriko, who prefer the contemporary transformation of traditional arts. And on the third floor are the works of Kojin Haruka, Nawa Kohei, Kato Izumi, and Tanaka Keisuke, which seem to express a possibility of intersecting relationships among quotidian artistry, visual standards, and modern life.

The practices of Watanabe Go, SHIMURABros, Kojin Haruka, and Nawa Kohei most resemble an archaeological exploration and reshaping of self-knowledge through experimentation with modern techniques. For example, Go created the series “Face” by copying and pasting an image upon the model of a face that the artist had made, as if covering a mold with human skin. The uncannily realistic result might confuse the viewer’s judgment. While Kojin Haruka’s works have the appearance of handicraft, their vibrant colors and complex structure belie strict technical control. In this simplest installation of inverted images, the implication is a possibility of realizing an ideal technical standard and abstract concept (such as absolute symmetry) in practice. These four artists share homology of practice and production methods. What they are showing through the works are not techniques themselves, but how technology alters our methods of observation and understanding. In other words, while our daily life is directed by different technologies, ultimately it is humans and their system of thinking that control technology.

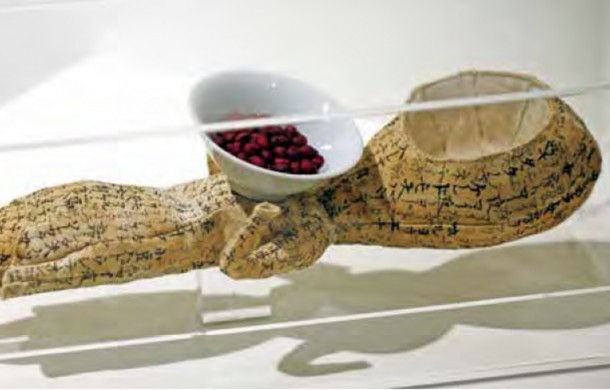

Alternatively, works by the remaining four artists rely on traditional handicraft skills and artistry— including calligraphy, drawing, and sculpture. The result is an attempt to discover an unknown world between history and imagination. Miki Taira, having studied calligraphy since childhood due to the influence of her scholarly family, tries a spatial presentation of calligraphy. First she dyed pieces of linen in barley tea, and then copied texts of traditional Japanese fairy tales that appealed to her onto the linen. Taira used the narrative to shape one of the images of her imaginary story. Murayama Ruriko’s experiments stem from the everyday, constructing installations organically with the freeform collocation of materials, such as handmade fabrics, manmade flowers and plants, ornaments, tree bark, and so on. Turning away from modern technologies, these artists focus on traditional methods, emphasizing the handmade and experiential qualities. The implication of their practices is a critique of and reflection on modern technologies. This raises the paradoxical dilemma of contemporary art’s encounter with scientific techniques: on one hand, modern technology is a necessary medium and method of contemporary art experimentation. On the other, the ethics of science and the ideology of technology have become a target of contemporary art’s reexamination and criticism.

This tension reveals the state of contemporary Japanese society and culture precisely. To this viewer, the question to be answered is, in a country such as Japan, how do history and reality coexist naturally? Or the traditional and the contemporary? In fact, to these artists there are no such dichotomies. The true direction and goal of their experimentations are to further understand the individual and unknown worlds. In this sense, perhaps what they value more is what heterogeneous reactions that such an exhibition will spark in Chengdu, in China. And for us, it should be just as well. (Translated by JiaJing Liu)