THE MUSEUMIFICATION OF CHINA

| 2013年05月10日 | 发表于 LEAP 18

BOOM

Concurrent with China’s rapid urbanization over the past three decades is an equally unprecedented museum-building boom. On average, nearly 100 new museums are being built annually across the country. During 2011, that figure reached a staggering 386 new museums— more than one per day. To better gauge the magnitude of this growth, at the height of America’s recent museum boom, extending from the mid 1990s to the late 2000s, only 20-40 museums a year were constructed. China’s museum boom is partially attributed to its recent efforts to accrue cultural capital, aspiring to increase the number of museums throughout the country to match international levels. According to the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, in China there are currently around 3,400 museums, equaling about one museum for every 380,000 people. Only cities like Beijing and Shanghai are comparable to developed countries, which have one museum for every 100,000 to 200,000 people. In a recent article, Guo Xiaoling, director of The Capital Museum, stated that China would need to create at least 43,000 museums in the future to catch up with the world standard, more than double the amount that currently exists in the US— a complete “museumification” of China.

ICONS AND URBAN IDENTITIES

This ambitious museum expansion plan extends beyond established first-tier cities inland to second- and third-tier cities, promoting culture while defining the civic identities of these new urban centers. The often iconic structures provide landmarks for newly planned government and civic centers, central business districts, cultural districts, and commercial developments. Many of the structures are designed by renowned architects, both international and Chinese, providing notoriety and cache. Aside from the benefits of civic “good intentions” and the promotion of vanguard architecture, there are potential negative consequences to building so many museums so quickly. Many of these museums, criticized by some as politically motivated “vanity” projects, are conceived and constructed inefficiently, without an established collection, curatorial mission, or leadership, resulting in the creation of vacant shells. Skeptics insist that museum construction funds could be better allocated to provide essential public amenities. Additionally, many of these built museums lack adequate long-term planning and funding, hindering their ability to maintain operations and achieve their stated mission and curatorial goals.

THE FUTURE MUSEUM

As China strives towards eventually surpassing its global counterparts in museums per capita, an opportunity exists to reconsider the museum project. As observed in the history of the museum, new types and forms were developed during times of expansion and increased public popularity (and when in crisis). China is undoubtedly experiencing both a boom in new museums and popularity. This is a critical moment to assess the museum and its potential role in contemporary China.

CONTEMPORARY ART MUSEUMS (CAM)

With a relatively short history spanning about 15 years in China, contemporary art museums comprise only 2% of museums in China. Although concentrated in the major first-tier cities, contemporary art museums and gallery districts are emerging in cities throughout the country. Though less popular than other types of museums, the contemporary art museum is essential in cultivating a cultural link to the past, present, and future, for both domestic and increasingly global audiences. How can the contemporary art museum position itself as an important center of cultural discourse? Through disseminating new voices and new forms of media, will the contemporary art museum become the primary platform for contemporary culture? These questions have motivated the China Megacities Lab to research the Future of the Museum in China, and specifically focus on the contemporary art museum, as we believe it provides the greatest opportunity to assess the current state of the museum and to ultimately redefine what the future museum might be.

CONCENTRATIONS

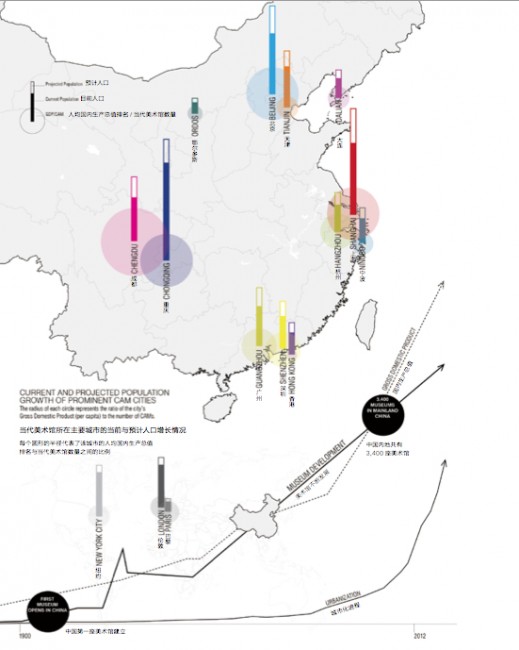

We chose to research and illustrate a comparative mapping of concentrations of population (current and projected), urban economies, and their relative ratios of museums and contemporary art museums. By looking specifically at a few key criteria, we sought to discover compelling relationships and emerging, underlying trends. Our research indicates that although there are more contemporary art museums in Beijing and Shanghai, per capita Chengdu was the most “contemporary,” with Shenzhen second. While Chengdu ranked first for population per CAM, it ranked sixty-sixth in GDP per capita and Shenzhen ranked third, behind Hong Kong and Ordos. Due to the small quantity of contemporary art museums, and the inherent ambiguity in distinguishing what qualifies as a contemporary art museum, we realize that the research might not yield any single conclusive result. We hope, however, that our research does provide alternative perspectives on the context of the museum in China. (Translation by Carmen Long)