WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE

| July 15, 2013 | Post In LEAP 21

3-channel video, 4 min. 35 sec. / 5 min. 23 sec. / 6 min. 20 sec.

The art world’s increasing interest in Southeast Asia in recent years is indisputable. Last year’s Art Dubai welcomed Alia Swastika to curate its Southeast Asian-focused “Marker” section. In late May, Christie’s Hong Kong offered up its largest-ever lot of contemporary wares from the region. Perhaps most tellingly, this year also witnessed the Guggenheim hold “No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia.” (Might one also suspect that the attention paid to Danh Vo, despite his éducation européenne, might also have to do with the artist’s ethnicity?) The reasons for this interest aside, it does not take much perspicacity to infer the similarities of Southeast Asian art’s rise to contemporary Chinese art’s own previous ascendance to “international” status. Granted, those in the West who worked to lend Chinese contemporary art the global stamp of approval faced an entirely different challenge. At least in some Western eyes, Chinese artists are a homogenous lot, their plights and concerns (if artists face these anymore) erroneously filed away according to the same set of expectations. Yet Southeast Asia is not one single country, nor do its artists speak in mutually intelligible tongues. Lumping them together in one bunch is a risky endeavor, prone to easy critique and a general slew of curatorial failings. Yet as seen at the Yokohama Museum of Art, this endeavor is not an impossible one. At moments, even, it seems like the only way to go about it.

For one, few of the included countries boast contemporary art ecologies developed enough to merit dedicated exhibition. For another, most of the included countries do share similar political and historical experiences (colonialism being at the top of the list). Yet the organizers seem compelled to dispel any potential contempt: with the title “Welcome to the Jungle,” they admit forthright to the dangers of overly naïve categorization. The “jungle” is a mysterious place, as savage as it is verdant, as diverse as it is unnavigable. Be you a collector or curator, heed its heady allure and tread in unprepared, and you face imminent threat. Yet here, the connotations are not so sinister as that (they cannot be; the idea is to promote contemporary art from the region, not tarnish it) and the jungle refers not so much to the tropical habitat as it does to its destruction in the name of deforestation and development (86% of Malaysian jungle gone in less than five years!), and to the diversity of form and approach with which artists confront this issue and others. As stated by Khairuddin Hori, Senior Curator of the Singapore Art Museum: “this exhibition demonstrates the practices of artists who continue to grapple… with intimate issues such as… personal and national histories and identities; rapid urban growth, economic successes and collisions; and the ethereal materials and strategies.”

Indeed, the 28 works of 25 artists from Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia, stretch across a wide spectrum of form and theme. At the museum’s gallery entrance sits Navin Rawanchaikul’s Where is Navin? (2007), an installation comprised of a life-size fiberglass replica of the artist dressed in traditional Indian attire and holding up one of several signs that spell out his first name in several different languages. The accompanying story is that the Thai artist, who is of Indian descent, set out to find other people in the world who share “the same name and similarities

of destiny.” Perhaps augmented by its grotesque visuality— what wax figure isn’t unsettling at first to living eyes?—the display of this work was a rather uninviting preamble. Would the works inside be undermined by concerns as trite as globalization and identity? For the opinionated viewer, would the exhibition overall share a “similarity of destiny?”

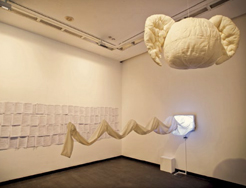

The only other work within the space to play the globalization card so blatantly is banker-cum-artist Lee Wen’s World Class Society (1999), but the effect is overwhelming only in its amusing panache. In something of a self-motivational speech calling for everything in Singapore to be “world class”—health care, education, sports, museums—the artist sarcastically sings the hymn of economic development. But forced to seek out the screen at a distance of several meters, through an adjustable-height white cloth tunnel hanging mid-air, the viewer is offered a pensive distance. In turn, she may question the ultimate value of progress—or simply pity a nation that really does try so hard to meet standards set by its former colonialists, even after independence.

Glass, cloth, badge, paper, video, dimensions variable

Elsewhere, there is Nge Lay’s image-based introspection of the loss of her father, The Relevancy of Restricted Things; Frank Callaghan’s series of unexpectedly alluring photographs of poverty in Manila; PHUNK’s flashy wall-mounted homage to the architecture and complexity of the contemporary city, Electricity (Neon); Ahmad Fuad Osman’s Recollections of Long Lost Memories, a spunky intrusion into Malaysian history through self-superimposition onto archival photographs; and the porcelain spoons of Chang Yoong Chia’s Maiden of the Ba Tree, which recount in miniature the story of a mother who mistakenly believes her son has been taken away from her. Be it vis-à-vis family, nature, beauty, or sheer possibility, one common referent of these works is that which is thought lost but perhaps is not entirely so. Parallels to the disappearing natural landscape—here to be read as one common vitality—of Southeast Asia are not too difficult to discern.

The composite weight of the above-mentioned works and others is heavily condensed into one dark room at the far end of the museum’s second gallery. Charles Lim’s 21-minute video All Lines Flow Out (2011) consists of a slow, floating journey through Singapore’s capillary system of monsoon drains. Its main protagonist is the camera lens, its perspective seemingly glued to a point just above the water’s surface. Silent long-takes on lush tropical marsh cut to shorter ones of rivered urban underpasses caged in concrete, but the water is omnipresent. The effect is menacing, its solemnity the invariable subject of the gravity of the universe. We do what we do, and we may do it well, but we are equally and eternally held to greater cycles of existence. With its simultaneous encompassment and transcendence of the other works’ more “tangible” concerns, All Lines Flow Out bears the brunt of this exhibition’s mission. Like a bookend, it does this in tandem with another work just inside the entrance of the gallery.

In Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s simple video triptych Thai Medley I, II and III (2002), the viewer finds herself intimate with the universe as well, albeit in a more destabilizing way. The artist moves among rows of unclaimed bodies in a morgue— some already blackened by decay, some floating in tanks half-full with what could only be formaldehyde— invoking aloud an ancient text about the “ideal of love” as a way of comforting these unwanted souls, of offering them their last rites. Even without seeing this woman speaking to the dead, hearing the near-holy lull of her voice (let alone, understanding her words), one understands that this is a powerful act of magnanimity. As for the curator, displaying this work is a powerful act of composure. On the one hand, including the video plays strongly into the dangers of over-exoticizing Southeast Asia, of presenting it as backwards and superstitious. But considering art’s unique capacity for incanting the primal, not including it would entail missing an opportunity to reground the contemporary viewer in humanity. For many audiences, the notion that art may still exist in a spiritual realm impervious to the sheen and sophistication of the gallery, the auction house, and even the museum, has been more or less pushed out of our consciousness— just like the jungle has been removed from the culture of much of Southeast Asia today. Or has it? Forget the mandate of the market, forget the risks of pigeonholing an entire region’s artists: Such savage reminders are where this exhibition succeeds.

Einar Engström