WHEN THE DOCUMENT BECOMES THE SPECTACLE

| July 17, 2013 | Post In LEAP 21

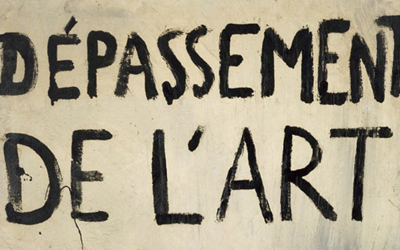

PHOTO: Jeanne Cornet, Guy Debord archives, manuscript division, BnF

“Un art de la guerre”—this is the subtitle of the spring 2013 Guy Debord (1931-1994) documentary exhibition at the Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF). An iconoclastic thinker, artist, and political activist, Debord scorned honors and organs of authority throughout his life and attacked what he called “the Society of the Spectacle.” Today, his manuscripts have been enshrined in the palace of France’s premier scholarly institution. Is it the greatest of ironies? No! BnF has emphasized that the purpose of assembling and exhibiting Debord’s archival material is to better understand this intellectual titan of twentieth-century France.

A few years ago, the foresighted and well-endowed Yale University attempted to purchase these archival documents from Debord’s widow, raising the hackles of the French. In 2009, the French government designated Debord’s manuscripts as national treasures, and in 2011, BnF purchased the archives despite a chorus of dissenting voices. The national library was naturally obliged to research and promote these valued materials, and this documentary exhibition is the result of two years of study.

The contents of the exhibition are abundant. From the perspective of contemporary art, our eyes are drawn to Debord’s views on art. How did his own works address their own spectacular nature? Following their efforts to transcend art, how did Debord and his comrades-in-arms use art to critique the ever-growing society of spectacle without falling into its traps?

A large curtain hangs at the entrance to the exhibition, the left side of it printed with a photograph of the young Debord. He stands in a courtyard with a knife in his hands and a smile on his face. On the right side of the curtain, a quotation: “People know that life is tiny. One knife, one tiny bullet is enough to end this long journey. They wait for us at every turn.” (1) A monotonous voice emits from the amplifier on the wall, and the accent already seems antiquated: “This is Guy Ernest Debord speaking . . .” The funny thing is, although this warrior against the “Society of the Spectacle” left behind few photographs, he was unstinting in recording his own voice. Perhaps he wanted to make it clear that it was the theorist and not the enragé who was speaking. (2)

On the other side of the curtain waits a rectangular exhibition hall, in the middle of which a small oval of space has been left empty. This space is separated from the rest of the room by a series of double-layered panes of glass, suspended in mid-air, holding Debord’s handwritten cards. The contents of the cards range from reading notes and journaling to criticism. Debord accumulated more than 1,400 cards like these during his life, and he kept them sorted into categories. He once wrote: “Spectacular domination’s first priority was to make historical knowledge in general disappear; beginning with just about rational information and commentary on the most recent past.” (3) Debord wanted to see for himself how his predecessors had observed the world, and he provided his own account of the times through his literary contributions. These materials form the basis of Debord’s practice of “détournement.” (4)

On the left side of the exhibition space, a symbolic opening in the glass panes brings visitors on a trip through documents, space, and time to the different periods of Debord’s life. His various activities—film, postering, writing, editing, the Letterist International (1952-1957), and the Situationist International (1957-1972) —can be seen as a whole, a work of art, addressing the question of how people should exist: how to struggle against spectacle. (5)

Rather than say Debord was a Marxist, it is better to describe him as part of an avant-garde that originated in Dada. Debord sought “a full and autonomous life combining individual and collective liberation.” (6) In postwar France, most people either believed in the promise of consumer society or agitated in favor of the Soviet regime and the Chinese Cultural Revolution, but Debord and his affiliates saw through the hypocrisies of capitalism and bureaucratism. In 1967, a few months prior to the publication of The Society of the Spectacle, Debord wrote “The Explosion Point of Ideology in China,” exposing the myths of the Cultural Revolution. (7)

In 1961, the Situationist International decided to abandon art practices and to continue their struggle in non-art fields and everyday life. A canvas scrawled with Debord’s childlike handwriting holds his new mission statement for the Situationist International, written in 1963: “go beyond art” was the first directive. (8) For the first time in history, artists truly gave up Art with a capital A and threw themselves into the struggle to change society. The Situationist International was the fuse that ignited the Paris Uprising of May 1968. Subsequently, Debord’s ideas received a greater degree of esteem and emulation, and a growing crowd of “post-situs” emerged in the 1970s. The exhibition includes, for example, an excerpt from a film by René Viénet (1944-) titled Chinese People, Keep Working for More Revolution. (9) The excerpt includes some propaganda footage from the Cultural Revolution with added parodic subtitles.

However, Debord criticized the post-situs for promoting the commercialization of revolutionary radicalism. (10) He thought that the new generation should not admire and emulate the Situationist International, but rather, seek to surpass it. Debord’s philosophy required continuous innovation and continual breaks with the past. Drawing perhaps on this resolutely combative spirit, he continued to write, translate, and publish following the dissolution of the Situationist International, and he also resumed working on films, “refuting praise and criticism.” (11) As the subtitle of the BnF exhibition indicates, Debord’s life itself was art in a broad sense: “the art of war.”

A few of Debord’s experimental films play for free outside the exit of the exhibition hall. Each interweaves diverse elements: western, documentary, performance, advertisement, and newsreel. “Humor and subversion, détournement and destruction”—these elements encapsulate Debord’s style. (12) Time and again, characters are thrust against their will into flirtatious dialogue or music, but this intoxicating narrative quickly gives way as scenes are spliced and the score is disrupted by Debord’s cool asides, subtitles in the silent-film idiom, and so on. Once we regain our senses, we seem to see Debord’s face, helpless, extremely sober, slightly sneering. Debord made his first film, Howls for Sade under the influence of the Letterists in 1952. (13) In it, the picture merely alternates between blank black and white. Later, he applied the method of détournement to “recover” spectacle: use it, appropriate it, expose it. Just as Debord states in his explanation of the game he invented, Le Jeu de la Guerre: the goal is to defeat your enemies either by completely eliminating the other side or by capturing your enemies’ arsenals. (14)

Guy Debord archives, manuscript division, BnF

Debord himself placed a great deal of importance on archival materials; he saw them as both historical testimony and source material for spectacle. Although he moved many times, he always meticulously preserved his own files. The exhibition notes include the following passage: “Perhaps he never thought that these archives would one day become a national treasure, but it is certain that Debord kept these files with a certain strategy intent.” Just like Europe’s religious wars in the Middle Ages, the problem of how to display images—and of how to display oneself—in the society of the spectacle leads to nuanced questions of visibility and invisibility. Turning Debord’s archives into a spectacle no doubt violates Debord’s initial intentions, but it would be much worse to bury or overlook his literary contributions. By mentioning this strategic intent, BnF tiptoes around the contradiction of exhibiting Debord’s rebellious philosophy at an institution of government authority.

Leaving the gallery, the visitor can look back at that curtain at the entrance printed with Debord’s image and words, and listen again to that monotonous recording of his voice. The scene is vaguely reminiscent of a Debord film: the appropriated image and words, the dislocated voice. Is it an imitation of Debord’s art, or a tribute to it? Is it a tactic of exhibition?

(Translation by Daniel Nieh)

Notes:

1. Unable to endure his frequent spells of neuritis, a consequence of his excessive drinking, Debord committed suicide on November 30, 1994 by shooting himself in the heart at his country home.

2. Over the course of his life, Debord was given many labels and descriptions, but he only acknowledged two: “enragé” and “theorist.” In addition, the Italian contemporary philosopher Giorgio Agamben (1942-) calls him a“tactician.”

3. Commentaires sur la société du spectacle, Paris, Champ Libre, 1988. Quoted from Laurent Jeanpierre, “Portrait de Guy Debord en archiviste,” Art press, cahier

spécial avril 2013.

4. “Détournement”was an artistic method often employed by Debord and his affiliates entailing the appropriation and reorganization of fragmentary images, text, and sounds to produce new meaning. Related concepts include dérive (derivation), jeu (games), psychogéographie (psychogeography), création de situations (the creation of situations), urbanisme unitaire (unitary urbanization), et cetera.

5. The Letterist International was established by Debord and others who had split from the Letterists. In 1957, the group joined other avant-garde groups to form the Situationist International, with a manifesto penned by Debord. He called for the continuous creation of new situations in everyday life in order to reform society. Beginning in 1961, the Situationist International transitioned from artistic to political practices. Following the Paris Uprising of 1968, the organization began to fracture, and it disbanded in 1972.

6. Laurent Jeanpierre,“Portrait de Guy Debord en archiviste,”as cited above.

7. “Le point d’explosion de l’idéologie en Chine,” an essay published in 1967.

8. The other five directives were: realize philosophy, jointly oppose spectacle, eliminate alienated labor, oppose authoritative experts, and universally establish worker committees.

9. Chinois, encore un effort pour être révolutionnaires!, released in 1977.

10. “Thèse sur l’Internationale situationniste et son temps,” an essay published in 1972

11. Debord released a film in 1975 titled Réfutation de tous les jugements, tant élogieux qu’hostiles, qui ont été jusqu’ici portés sur le film “La Société du spectacle.”

12. Patrick Marcolini, “Les héritiers de Guy Debord,”Chronique, n. 66, 2013.

13. Hurlements en faveur de Sade, released in 1952.

14. From the writings of Debord’s second wife, Alice Becker-Ho: Le Jeu de la Guerre, éditions Gérard Lebovici, 1987; édition revue, corrigée et augmentée, Gallimard,

2006. Debord began concocting this chess-like game in the 1950s and patented it

in 1965.