Ink In The Twenty-First Century: A Humble Disquisition

| December 23, 2013 | Post In LEAP 24

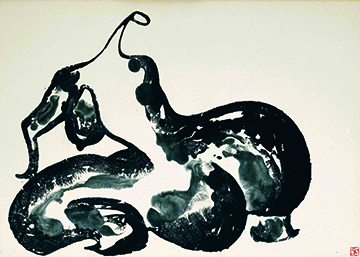

Ink is ancient Oriental culture’s great contribution to the world. Compared to artistic media such as oil painting and miniature painting, ink painting is a result of the free and spontaneous flow of water and ink on paper, and the dilemma between the controllability and uncontrollability of the four materials—brush, ink, water, and paper— constitutes its unique cultural character. Throughout its thousand years of development, it has carried in its genes the inclination to depend on intuition and experience, which is typical of Oriental culture. It manifests a special mode of spiritual communication, by which one may comprehend the macroscopic world through its microscopic details. At the same time, ink painting has been integrated into all manners of traditional culture—Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian beliefs, the garden, the study, elegant gatherings, scholarly playthings, and so forth—so contemporary critics tend to consider it not only as an artistic language and medium, but also as the convergence of a lifestyle and cultural rituals.

After a thousand years, the eighteenth century ushered in an era of formalism in ink painting. Later, under the colonial pressures that China faced in modern history, ink painting and its modernization became especially complicated. With the May Fourth Movement, which championed the pursuit of democracy and science, ink painting started to borrow from Western art. In the nearly 100 years that followed, ink painting expanded its vocabulary into realms of realist, expressionist, and even abstract art, and witnessed the arrival of masters such as Huang Binhong, Pan Tianshou, Qi Baishi, Xu Beihong, Lin Fengmian, and Wu Guanzhong. Nevertheless, the continuous development of contemporary ink painting practice does not negate the fact that, with the process of modernization brought in with the twentieth century, the traditional lifestyle and cultural rituals compatible with ink painting culture have been steadily disappearing. As modern civilization changes our culture, so it does our lifestyle. It is evident that the previous practice of creating and viewing ink paintings in the study or at elegant gatherings has been significantly affected, as has ink painting production in the past century.

When we look back at the ink revolution of the past 100 years, it is not hard to see—and it should not be forgotten—that the innovation in Chinese painting initiated by Kang Youwei and Chen Duxiu was rather destructive to the millennium-old tradition. Every round of innovation was also counterbalanced by the activities of “preservers of tradition.” These included Chen Shizeng, Pu Xinyu, Zhang Daqian, Huang Binhong, Dong Xinbin, and Huang Qiuyuan, who was ostracized in the 1990s because of his “deterrence” to experimental ink. Recently, there have been the “New Literati Painting” and “Cosmopolitan Ink” movements. However, we need to be fully aware that the modernization of twentieth-century China was irreversible, leading to an inevitable tension between Modernism and traditional artistic language. This tension has promoted certain mediums and language, while obstructing, forgetting, neglecting, and even effacing others. For example, the realist direction, envisioned by Chen Duxiu and advanced through Xu Beihong, Jiang Zhaohe, and the New National Painting Movement, has become New China’s mainstream art. Kang Youwei’s proposal of reforming the weak and stylized literati painting through gongbi (fine brushwork) and academic painting, on the contrary, was not put into practice by artists until recently.

Starting last year, the concept of “New Ink” began to appear in auction catalogues, lectures, and in the media. But if we are aware of its evolution, as outlined above, we will realize that the so-called New Ink is a confusing and imprecise concept lacking a scientific definition. What lie behind the popularity of “ink paining” are market incentives. During economic doldrums, the opacity of tax laws and the utilitarianism within contemporary art largely inhibit the growth of the contemporary art market, a change that impels contemporary art to reflect upon itself. Meanwhile, New Ink is now becoming a New Territory with which international auction houses substitute for the Chinese contemporary art that is not doing as “well” as before.

Undoubtedly, if the discussion of New Ink is carried out against this background, there is an inherent theoretical deficiency: if following a market logic that uses ink to hedge against risks in contemporary art, “ink” is subconsciously placed in opposition to “contemporary art.” The result—that ink is still excluded from contemporary art—runs counter to the trend of dialogue and integration between contemporary ink practice and contemporary art. If this situation remains unchanged, the so-called “new” ink could only be a commercial gimmick. Whether it is abstract ink painting or the ensuing experimental ink, New Literati Painting or the recent exploration of the gongbi style, several generations of artists in the past 30 years have greatly advanced and enriched ink’s modern expression, which should logically result in important artistic phenomenon in the twenty-first century. If these three decades of experimentation continue, the results will require serious research and study. Scholars and artists should work together to recount its history, modify critical terminology, and provide a cultural explanation for the ink medium. Rather than discuss what New Ink is or should be, we should discuss how to infuse new energy and thinking into ink of the twenty-first century, incorporating the establishment of theory, historical review, and exhibition culture.

Ink’s drastic transformation throughout the twentieth century has since the 1980s been gradually simplified into the “ink problem.” The reason is that ink’s expressiveness—rooted in the “ink play” tradition—naturally corresponded to modern expressionism or the discussion of materiality in the context of the ’85 New Wave, and thus naturally acquired attributes of the “avant-garde.” It also reflects the lack of ink criticism and theory. Generally speaking, preexisting ink theory has come from two sources. The first is the discourse of traditional painting. The theories based on this emphasize constructs such as brush-and-ink or breath-resonance, which are rich in tradition but too dependent on cultural mentality to give qualitative definitions and descriptions. The other comes from the formal analytics of Modernism. Critical theories centered on texture, brushwork, spatial structure, and so on are conducive to qualitative analysis, but miss the cultural psychology buttressing ink culture. These two discourses have so far existed in two systems that do not communicate with each other, and can only partially respond to certain aspects of otherwise rich ink practice. The development of ink in the twenty-first century is concerned with not only artistic creation, but also with the construction and development of ink theories from an international standpoint. Brush-and-ink theory should not overshadow formalist theory, nor should the latter reform the former. The urgent question now is how to incorporate the critical vocabulary and theoretical questions of ink into contemporary art discourse, or to make ink relevant to the present, so that these new words and expressions can on the one hand maintain the traditional cultural mentality and memory, while connecting with contemporary theoretical questions on the other. For example, we should begin to think about how to use contemporary theory to interpret and invigorate traditional painting theories such as the Six Principles. The process of modernization in the twentieth century undoubtedly deprived traditional cultural mentality of its cultural nourishment. As a result, traditional painting theory is simplified in its modern translation, or is directly projected into the Western traditional painting discourse. For instance, in the Six Principles, “plotting and planning, positioning and placing” is simplified as composition, and “following the kind, application of color” is simplified as color. Instead of conservative nationalism, how can we utilize contemporary theory to activate and enrich these traditional idioms so that they assimilate as a definable scientific theoretical language, able to be reintroduced into contemporary criticism? This is not only the core issue of twenty-first-century ink theory, but also that of Chinese art generally.

Of equal importance as the issue of theoretical construction is the question of how to dispose of the “cultural nationalism” in our subconscious. Powerful cultures tend to inspire internationalism, whereas weak cultures tend to induce nationalism. As ink is constantly marginalized in contemporary art, a kind of “cultural nationalism” emerged within the circle of its creation and criticism. When we talk about ink today, the perimeter is set around China, or even merely Mainland China. But according to existing information, the reality was far more complex. As discussed above, “abstract ink painting” occurred in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s respectively, but differed and even contradicted with each other with regard to cultural motivation and evolutionary process. The systematic study of these events could perhaps alter our assessment of these styles, while understanding the practice of overseas Chinese artists also adds to our knowledge. T’ang Haywen was a Vietnamese painter of Chinese origin who lived in France and passed away in the 1990s. Recent research of his ink art creation is concerned with his close connection to contemporary artists Zao Wou-ki and Chu Teh-chun, and also the consensus between Fluxus and his ink-based video art from the 1970s. Once we discuss ink in the framework of contemporary art, and introduce dimensions of performance and installation, or if we expand our field of vision even further, we will see that outside Chinese ink, there was ink experimentation in Japan and Korea, within the Gutai group and Mono-ha, among the Asian members of Fluxus, that the abstract expressionist Mark Tobey studied calligraphy in China in the 1930s and imported Chinese writing into the New York School. What is the relationship between these creative activities and Chinese ink? Would a comprehensive study lead to new perspectives and new issues in ink culture? We should hold the belief that as the research advances, it will become plain that ink’s relationship with Modernism and even contemporary art is not simply based on a model of impact-and-response. There are far more intricate connections there, and a clear understanding of them would surely stimulate new artistic creation.

Ink’s relationship with contemporary exhibition culture is an equally serious question. The main formats of presentation of Chinese painting include album leaves, hanging scrolls, handscrolls, and sets of hanging scrolls. From a historical viewpoint, ink’s spatial forms and rhetoric were far more complex than what we imagine and deploy today. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, the viewing modes of ink painting had fine distinctions. For example, letters by Ming and Qing artists reveal that large-scale landscape covering a set of hanging scrolls was considered vulgar by the literati then, while album leaves, handscrolls, and small portable hanging scrolls were considered elegant. Basically speaking, these formats allowed easy appreciation and great mobility, with the viewing activity able to move from the wall to the table. This ritualistic mode of appreciation is a very important viewing mode for Chinese painting. But the core philosophy of contemporary exhibitions is based on the “Modernist” concepts of “public space” and “space for cultural worship,” which do not pertain to the culture and rituals of traditional study viewing or elegant gathering. This change in space can also be regarded as a “castration” of ink by Modernism. From the twentieth century on, the modern exhibition system has drastically altered our way of exhibiting ink art, an effect that has then changed its language, at least with respect to space. Since the Ming and Qing dynasties, the exhibition of Chinese painting has most commonly taken place in “spaces for private experience,” whereas contemporary exhibitions are held in “spaces for public worship.” The constant mention of Song painting in recent times could be explained by its compatibility with the modern exhibition system. The New National Painting Movement in post-Liberation China met the demands of this kind of spatial worship and made great achievements, but at the expense of the obsolescence of many other forms and expressions. Large hanging scrolls that artists used to despise have developed because they best fit this modern exhibition system. In contrast, handscrolls and small hanging scrolls have gone downhill. Handscrolls that need to be unfolded slowly are the most difficult to exhibit, because they cannot satisfy the contemporary requirement that any given number of people should be able to view the objects in a so-called public space. Of course there are curators who wish to restore traditional gardens and studies for exhibition, in a thorough revival of the past. Should we give up traditional forms? Should we transform the modern exhibition space? Or should we reform our methods of language and display, and how? These are questions for both curators and artists.

Perhaps only when these fundamental questions are addressed will it be possible for us to foster “new” ink in the twenty-first century.