LOST IN AMSTERDAM

| March 11, 2014 | Post In 2014年2月号

Artist Cheng Ran is on a two-year residency at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, where he has prepared a visual diary of his present work and life for LEAP.

Amsterdam is smaller than I imagined. Traversing the entire city by foot takes approximately one hour and forty minutes; I have done it many times. From Amsterdam Central Train Station, concentric semi-circular canals extend out, forming the structure of the whole city. Thence, you could begin walks from opposite directions and arrive at the same destination. Of course, all streams of people converge at the Red Light District. It is the heart of the city, red like blood.

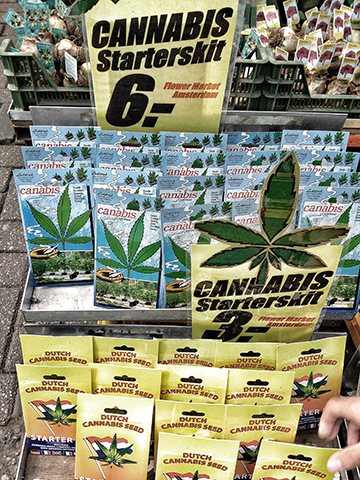

Marijuana seeds are legally sold at flower markets and are thoughtfully packaged so you can take them on the airplane.

The doorbell of the artist’s resident-studio still retains the name of a guest from years ago, Yang Jian, an artist who resides in Beijing now. Three years ago, while in Rijksakademie, he lived in the same studio.

The former cavalry barracks Kavallerie-Kazerne is now home to Rijksakademie, or the Royal Academy of Visual Arts—even though everyone makes it clear that it is not an academy. The residency program, which lasts two years, supports 50 artists from around the world; it began in the late eighteenth century when it was still an academy, the alma mater of Mondrian.

My Indian friend Aditiya partying in his studio. There is never a day when he is entirely sober. From his mental working state I first begin to understand the form and meaning of a certain kind of abstract work. Recently he was in a group show in England’s Lisson Gallery. He has a bright future ahead of him.

OT301 in south central Amsterdam is the first bar I visit after arriving in the Netherlands. In the 1990s, it was a squat inhabited by a group of artists. Before that it was a film academy. By law, these artists can legally occupy the rooms, paying low rent. Now it has evolved into a bar, a restaurant, a performance space, and an independent movie theater with artist studios. It is hidden deep in a residential area, but as seedy as it is inside, it is hard to believe that there are strict rules and regulations. At the door stand two large men shivering in the cold. They remind every arriving guest that outside the entrance, loud noises, smoking, and drinking are all prohibited. Perhaps precisely because of this, the balance between two sharply contrasting worlds can be maintained. Down the street a graffiti artist has tagged the corner wall in big letters: are you a bird?

As a mainstream art organization, the Rijksakademie offers much more than just the two-year residency and related financial, technical, and scholarly support. It emphasizes exchange between artists, integrating artists into the overall system, working with foundations, and establishing contact with the art world. All day long, there are parties, seminars, and studio visits that allow everyone to truly develop real connections, not just remain strangers. In one of the travel and discussion activities in the beginning of the year, we go to the northernmost island of the Netherlands for a few days, to bird-watch in the frozen wilderness, ride bicycles, and discuss our work among the miniature horses we see everywhere we go. Due to changes in Netherland’s policy concerning the support of art, all the budgets are shrinking. Before, trips were arranged to Iceland, Morocco, or other more relaxing locations. Although not everyone is optimistic, nothing can stop the all-night revelry. Perhaps future trips will be made to China.

We pool our money together, purchase an engine, and repaint the little academy boat. Come summer, we float it down the canal. I am pleasantly surprised to run into an old friend, Gabriel Lester. We met in Shanghai. He shows me the erotic massage parlor where he was a part-time doorman when he was at Rijksakademie over ten years ago.

The Oriental City Restaurant in Chinatown was the location of the triad negotiation scene in Young and Dangerous, the classic Hong Kong movie from the early 1990s. A few hundred meters away in the Red Light District is where Andy Chan Ho-Nam, played by Ekin Cheng, jumped into the river from the bridge.

I go to Netherlands’ oldest cinema, The Movies. It is more than 100 years old. The cashier asks which movie I want to see. I say I want to see the best looking theater. For me, it doesn’t matter what film is showing—I will always remember the theater that showed it. The two can never be separated. My next destination will be the last struggling porn cinema left in the Red Light District in the twenty-first century.

I spend Chinese New Year at the home of legendary Icelandic artist Sigurdur Gudmundsson. Pictures of the land art he made in Iceland in the 1970s have been forwarded like crazy on Weibo. Now he spends a lot of time in Xiamen, and with his wife has established the Chinese European Art Center. He is still full of energy; he even gave himself a Chinese name, Si Gudu. The old gentleman warmly welcomes us to celebrate Chinese traditions. He makes us dumplings and a pot of instant noodles. I will never forget it.

This bar is called The End. I write it into my novel.

In Amsterdam, people revel deep into the night, discussing art, and life. Even the drunken, defeated erotic dancers, with their fluorescent eyelashes, can make you feel young and healthy. Everything is like a giddy dream. It won’t last long but won’t disappear either. As seen when comparing the clocks of two time zones, today is tomorrow.