THE MEASUREMENT OF MOURNING

| April 25, 2014 | Post In LEAP 26

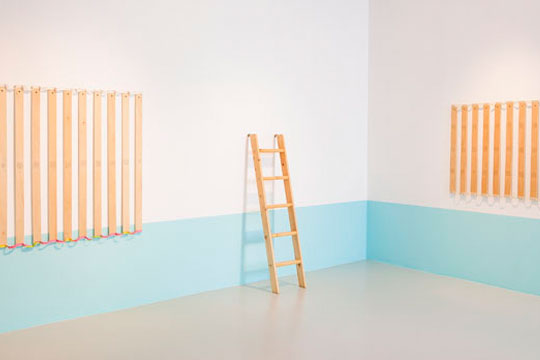

Pencil, acrylic gel medium, oil-based ink, screws, pinewood components of a set of used bunk beds, dimensions variable

How long is mourning?

(Dictionary, Memorandum): eighteen months for a father, a mother

——Roland Barthes, Mourning Diary, October 29, 1977

Roland Barthes started writing his Mourning Diary, October 26, 1977 – September 15, 1979 the day after his mother’s death. Over this period of nearly two years he completed a number of lectures, essays, and his volume of notes on photography, Camera Lucida. The same mourning process took Au Hoi Lam 24 months—from My Father is Over the Ocean to Shanghai Postscript.

Pencil, acrylic gel medium, oil-based ink, screws, pinewood components of a set of used bunk beds, dimensions variable

In Mourning Diary, Barthes worries that others will think he is taking advantage of his family’s misfortune as the subject matter for literature. Similarly, My Father is Over the Ocean was not initially intended to be an exhibition. After her father’s death Au Hoi Lam received an invitation to exhibit at Osage Hong Kong. Only later, during the course of the long grieving process, did the whole project gradually take shape. Coincidentally, My Father is Over the Ocean and the completed project from Au’s recent residency at Osage Shanghai both opened in March, the anniversary of her father’s death. This gives the two exhibitions, mounted during different stages as they were, their own emotional and intellectual context.

Grief is an indescribable feeling that over the course of two years can repeatedly intensify, pare back, and bring you back to serenity. Universal human feelings probably only reach their greatest resonance when death is supposed. The performance of personal suffering is a rehearsal of the memory needed to avoid forgetting the suffering. For Au Hoi Lam, Shanghai Postscript is a sequel to My Father is Over the Ocean.

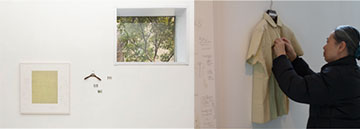

on the 4th of May 2001, 2014

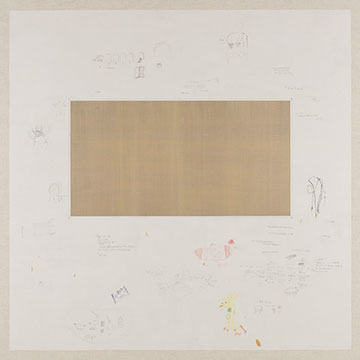

Pencil, colour pencil, acrylic, linen, wooden frame, wooden

clothes-hanger, instant photograph

approx. 122 x 250 x 5 cm

Au Hoi Lam’s Shanghai Postscript is a narrative joined together by a shirt. In 2001, her parents bought her a gift in Shanghai, a shirt she kept for many years. Before coming to Shanghai, she had the idea to use this shirt to make an artwork. But she forgot to pack it, and asked her mother to bring it from Hong Kong and then personally hang it up on the opening day of the exhibition. Au recorded this by taking some Polaroids and then removing the shirt, leaving only the photos and the hanger on display. In doing this, the image of her mother was left out; she became a hidden “envoy.” On the hanger is written the time Au owned and wore this shirt, marking the memory of her body. Compared to the image of her mother exhibited a year earlier (taken in Miyazaki, Japan, a solo figure viewed from behind looking out at the north Pacific Ocean), the emotion here is restrained and detached.

Pencil, colour pencil, acid-free paper (daily-diary), copper nails, corkboard, acrylic board and wooden frame

A set of 13 pieces, 100 x 100 x 2.4 cm each

It is obvious that the color blue represents the sea. The walls of each room in the exhibition space have been painted in subtle variations of blue. My Father is Over the Ocean gives the death of her father a beautiful home. He worked on the sea his whole life, and returns there one last time. In Dad, What Shade of Blue did You See Today? (2014), the words to the song “My Father is Over the Ocean” recur while blue lines represent the surface of the sea. Pages taken from a blank diary are pinned onto three sets of cork bulletin boards. Au has repeatedly “written a picture” on the pages, as if having a conversation with herself, or as if rebelling against the one who has left. These feelings reach their peak in Sixty Questions for my Father (Or Myself), which is created from the wooden planks of her father’s bed.

Meanwhile, I will Take Care of Each and Every One of Them is made from the screws, dowels, and nails from the wooden frame of the bed. At first she wanted to sort them out and “name” them; only later did the Sixty Questions for my Father (Or Myself) appear on the wooden planks.

Acrylic, oil-based ink, fragment of a printed cotton bed sheet, cotton embroidery thread, 224 pieces of nuts and bolts of a used bunk bed

Dimensions variable

The motivation behind Au Hoi Lam’s work is the need for expression, like that of a writer. With a method similar to meditation she contemplates the relationship between humans and space. For the physical labor and each piece that is produced, emotions and the body are involved. By emphasizing the inclusion of craft in a systematized and industrialized environment, many complex experiences in the external world can be given clarity from the slow process of handicraft. Au tirelessly numbers and time-stamps objects, a kind of self-systematized working style that could seem meticulous to the point of being obsessive-compulsive. For the artist, objects which have been numbered can be clearly differentiated. Each object attains its own individuality, the number becoming the name and identity of each object.

Reflecting on the numbers and tables that appear again and again in Au Hoi Lam’s work, these measurements give a feeling of order to the whole emotional narrative. She places the narrative expression of her paintings into a rational frame, so they can be understood in terms of simple rationality and calculation. This makes Au’s method of dealing with the huge and personal subject of grieving for her dead father seem far from impulsive. Under her brush, every detail of her grief is presented subtly and simply, dealt with cleanly, and leaves no mark.

Pencil, colour pencil, acrylic, linen, wooden frame

122 x 122 x 5 cm

The everyday actions of writing a diary by hand and making notes become in Au Hoi Lam’s paintings a personal archive. In Memorandum, she treats the construction and texture of space like a continuation of her painting methods of recent years. For her the act of writing is for reviving and reviewing, and also for commemorating the reappearance of past people and events. In another part of My Father is Over the Ocean, a booklet titled Memorandum (Father) exposes the story behind the work. A section of text has been deliberately rubbed out, a blank space between the private and the public.

Everyday objects placed in the space, the symbols of everyday life, and a creative impulse driven by personal life experience— these come together in a vivid living scene. This style is shared by Au Hoi Lam’s contemporaries in Hong Kong. In an overwhelmingly results-oriented age, it has almost become normal for the usefulness of artistic production to be the absolute measure of its value. There is virtually none of this in Au’s work. Her work has more to do with life experience and emotions. Her art is not only a form of emotional expression; it is also about making connections between emotions.

Au Hoi Lam, who is now pregnant, is living in Shanghai on a residency. The newborn baby will become a metaphor for the emotions in the exhibition, and grief will be transformed and finally pass. One life has ended, a brand new one will take its place.