ZHANG PEILI: BECAUSE…THEREFORE

| July 17, 2014 | Post In LEAP 27

Sound installation, track, speakers, computer,

fluorescent light tubes

Light, sound, space, and time effectuate four dimensions inseparable from the fulfilled human sensory experience. The quotidian, however, tends to overlook their existence. Art tends to emphasize it; herein lies art’s ontological value. The more illuminating an artist’s delineations of the contours of these dimensions, the more lauded the artist. Zhang Peili is a very lauded artist.

Working primarily through video and installation, Zhang Peili has over the past three decades gruffly muscled his way into the Chinese art history books, while resisting the trappings of embellishment. Often, the object seems no more than sheer vehicle, the core of his work instead directly offered to the viewer (one might say his subject) in the form of heightened awareness. Zhang’s special blend of awareness—constructed via affect; see LEAP 19—carries tones of the social, the political, the spatial, and the corporeal. In “Because…Therefore…,” these tones appear slightly more brightened than before, their emergence from their respective more refined.

Video projection, color, sound, 22 min. 9 sec.

In the slick, three-screen Image Unveiled, sight seems primary, but it is not what consummates the artwork. In front of each of the images—LCD photos that in their wispy composition look more like digital paintings—an infrared sensor is installed. When it senses the arrival of a viewer, the resolution of the image is increased ever so slightly. With the 5,000th visitor, the image attains its highest possible number of pixels, and the photos are finally fully revealed. (In each, we come to behold human skin marred by scars or bruises. The newfound clarity becomes brutal, ours, and easily fleshed out within the realm of biopolitics.) In this process, Zhang appoints the most ancient of mediums to dominate the artwork: its fullest being demands a particular slope along the axis of time and space. Instead of giving the audience instructions, as Zhang violently strategized with his text-based works of the 1990s, stringent and specific conditions are required of the artwork itself.

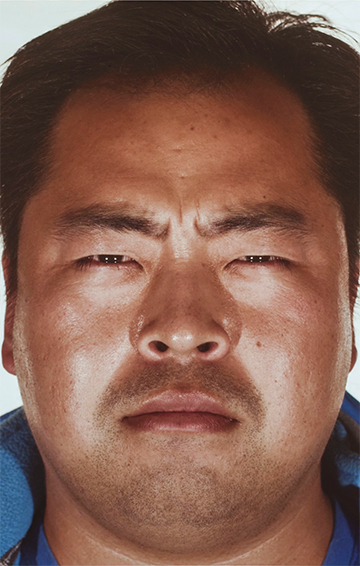

The massive video piece Portraits of 2012 is interactive in an irregular way: it forces the audience into unwitting compliance. From complete darkness and accompanied by a thunderous boom, a blinding flash of light outward from the screen marks an equally powerful flash into the screen. Zhang enacts a strategy of mimesis: the writhing expressions of the filmed subjects, squinting as if in pain, are a mirror of our own. Once we recognize our status as passive performers of the artwork, this revelation swiftly transfers into physical self-cognizance of the most immediate sort; if Zhang allows any space for the imagination, this space is countervailed by the artist’s persistent yet covert sociopolitical consciousness. The easiest conclusion available is that Zhang means to show us the pain of seeing. (Because reality is not ideal, therefore ignorance is bliss.)

In the upstairs gallery, the pain of listening is also drawn out, albeit draped in a overwhelming spatial presence clearly rooted in the suffocation of A Necessary Cube (2011). Collision of Harmonies is a mechanical sound installation, formed of two loudspeakers tracked on the ceiling above the alternating flickers of fluorescent light tubes on the floor. The architecture of the space is highly pleasing. From the far end of the room, the speakers respectively emit male and female chanting, also pleasing, that are mutually rebroadcast via microphones pointed at one another— the closer they are, the more amplified the intensity of their interaction (and ours). Magnifying the transition from the sublime to the grotesque seen in Image Unveiled, the work ultimately unleashes upon us an unbearably high-pitched feedback of discordance. (Because you endure the existence of the object, therefore you may understand the object’s function.)

The interested subject will note that in experiencing these three works, as with the hardships of life, you can condition yourself to cope. Zhang’s is a formalized demonstration of rampant self-desensitization, a reminder of how we have learned the flashes not to blind; the sounds not to startle; the pain to recede and the cuts and contusions to fade into memory. The cacophony that is our blood and guts, in other words, can be repressed. (Because you can, therefore you go on.)

Interactive installation (still image controlled by sensors and computer), color, silence, sensors,

LCD monitors, computer

In the opinion of this writer, Zhang Peili’s consistent command of his viewer’s cognition is remarkable. And yet, the hubbub surrounding this much-anticipated exhibition was succeeded by the twang of fault-finding: the artist hasn’t broken any new boundaries. But why should he? Zhang’s legacy lies precisely in such orchestrations of affect. His unceasing, systematic exploration of his singular artistic language is admirable, and necessary, not in the least for its defiance of the art world’s mindless demands for forward movement. In other words, the spectator who cannot accept the art on its own terms likely needs to break some boundaries of his own.