A PAST THAT IS NOT TRULY PAST

| November 10, 2014 | Post In LEAP 29

WHEN I ARRIVED in Hong Kong in 2011 I promptly settled into a flat at the meeting of Rutter Street and Pound Lane in Sheung Wan. Para Site was just down the hill, about 45 seconds by foot. It had been there already for 17 years. Coincidentally, we are both leaving at the same time: I from Hong Kong entirely with an uncertain return date, if any, while Para Site shifts to bigger digs across town to accommodate their increasingly ambitious, exuberant exhibitions.

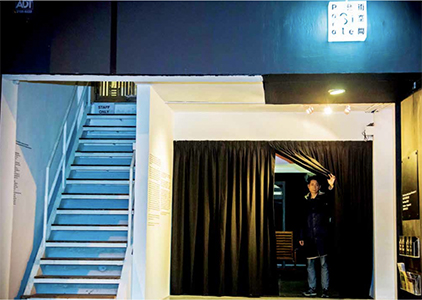

Kwan Sheung Chi’s week-long durational performance The 21st Century Undead Coterie of Contemporary Art at Para Site marks the organization’s transition out of its old location. The front façade of the gallery has been removed, as if the building were being dismantled piece by piece before the big move. Kwan occupies the ground floor, with a series of events, including film screenings, that address the themes of time and change. He rearranges his sleeping patterns to coincide with daylight hours. His performance invites reflection on the nature of change: its origin, its energy, and its measurement. What adds gravitas to this meditation is that his performance also coincides with the mid-autumn festival’s nod to the loops of the lunar cycle; the winding down of the ghost festival and retreat of the wandering lost souls of the past from the city; and charged hopes around “this-worldly” changes to the electoral system and the redistribution of political power within the Special Administrative Region. I want to contribute in a small way to this reflection on change, and to add examples to the already packed table through a miniature history of the changes both Para Site and I have witnessed in our shared corner of Sheung Wan over the past three years.

One night I was sitting on the windowsill two shops away from Para Site on Po Yan Street between Hollywood and Tai Ping Shan, and began chatting with an older woman. It was two years ago, around the time of the ghost festival. She told me about ghosts. “Nothing ever dies,” she said. “Things only change their form. To live in a world full of ghosts means that you live with a past that is not truly past. It is not dead, but always with us. What anthropologists call ritual around the dead here in Hong Kong is really just a way of doing history, of living with the past. Living with the past is the same as learning to live with neighbors, kids, husbands or wives. What is mysterious and troubling is not the ghost but the agent of selection: what makes one form change into another? How do I know if I will become a tree or a ghost when I die? This is the terrifying mystery.”

Beside Para Site, uphill on the corner of Po Yan Street and New Street, was a convenience store. They would lay down flattened cardboard on the inside of the threshold so that your feet would gently crush its corrugations. Inside they had the largest pile of adult diapers I’ve ever seen, from floor to ceiling. No doubt this was the supply for Tung Wah Hospital across the street. They have now been replaced by an Australian clothing shop selling trendy, infantilizing ballet shoes for everyday wear. The colors of the shop and everything in it are pastel with a home magazine vibe, no doubt comforting to some. I rarely see anyone inside.

The furniture maker in the building adjacent to mine on Pound Lane and Tai On Terrace was replaced by the pretentiously named Gourmet Shop, which the owners understood to mean selling American peanut butter and Japanese seaweed. My neighbor, who was going through family troubles about a year and a half ago, would sit on their stoop drunk in the middle of the day, embarrassing the customers at the posh Viennese café next door, which opened a few months after my arrival. I’ve noticed that when people are consuming posh things, they really don’t like to witness the unpolished dimensions of life. The gourmet place closed down and my neighbor seems to have sobered up.

The gourmet place was then replaced by a yoga studio. It commissioned a graffitied façade so as to impress the neighborhood with its imported street cred. Two years ago people made furniture; now people in very tight athletic wear began parading their bodies as ornaments affixed to narcissistic aspirations of toning and health. Before, it used to smell like fabric glue, and the furniture maker wore blue work pants and cheap shoes, smoking while driving staples from a gun into upholstery.

It’s been hard for me to watch almost all of these changes because their motivating forces are the restless, superficial values of contemporary consumer capitalism. For this system, change is always banal: from perfume to pillow shop, from salted seaweed to hip hop yoga classes. As Para Site and I move on, the manic unsettling forces of superficial change will surely continue at their ever delusional pace, rearranging Sheung Wan—for the worse.

Kwan Sheung Chi has transformed the ground floor of Para Site into his temporary home. With its façade removed, he has divided the inside from outside with a thick black curtain. The inside is dark and cold, with the minimal furniture necessary to support an everyday life reduced to sleeping, drinking, and watching movies. He’s not eating, smoking or making love (though he does, unfortunately, have the internet, which threatens the legitimacy of the project!). The interior space throbs with lights that slowly change color and a clock lying flat on a spinning turntable that interpenetrates repetition with difference. Kwan returns us to our initial question, in Sheung Wan and beyond: what makes change? What is the mechanism of selection at work? What is a difference that makes a difference?