THE 10TH GWANGJU BIENNALE: BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE

| 2014年11月03日 | 发表于 LEAP 29

Founded in 1995, the Gwangju Biennale has an international reputation based partly on its status as a public memorial to the Gwangju Massacre, and partly on the usual elements of a biennial: the choice of curator, theme, and quality of work. The ten shows have spanned 20 years, the first 10 of which coincided with the height of popularity for biennials, when art remained more open to political, social, and cultural influence. As the space for independent curators shrinks, biennials become thoroughly mechanized, and once-radical criticism gradually turns into a stale and politically correct formula, the biennial itself becomes akin to a large mainstream museum exhibition.

Jessica Morgan, the artistic director appointed by this year’s Gwangju Biennale, is a typical museum curator. Her chosen theme, “Burning Down the House,” seems to imply a desire to completely overturn and revisit the first ten years of the Biennale, and she goes to extremes to implement this vision. The title comes from a song by the American band Talking Heads; French electronic musician DJ Joakim remixes three versions of the classic track playing at the entrance to the main exhibition hall, in a passage between two high-rise buildings, and at the exit of the exhibition. We are told that these ambient mixes contain different levels of abstraction, degradation, and distortion, and t hat t he version at the exit is closest to the original. Apart from this appeal to our sense of hearing, anyone who passes through the Biennale will recall the choking smell of burning wood smoke emanating from chimneys on the plaza, new work from Sterling Ruby. The stoves are placed in conspicuous locations in several exhibition halls; Ruby is skilled in metalwork and provides a faithful interpretation of the show’s theme.

As one enters the show, the theme of burning is strengthened by the pattern on the walls: British-Spanish design collective El Último Grito proposes a large-scale pixelated photograph of fire as the background to most of the works in the exhibition rather than the typical white walls. This intervention may save the organization and layout of the exhibition space from being excessively structured and conservative, but not every work sits comfortably. Morgan has divided the exhibition into five existing spaces. Room One explores individual struggles against totalitarian control and oppression using the body as the main medium. Videos of three performance pieces by artist Lee Bul, who once represented the Korean pavilion at the 1999 Venice Biennale, are played in their entirety in a darkened space. Hung from ceiling are the props she used when performing Untitled (1989) on the streets of Japan and Korea: two monster costumes that remind us of blood, filth, and mangled limbs. These early, poor quality video records provide a visually shocking material sample. South African artist Jane Alexander recreates a large group of installations for this show. Drawing on Shakespeare’s Macbeth or the van Eyck brothers’ Ghent Altarpiece, ranks of creatures with animal heads and human bodies recall power structures and violent methods of control. Aside from a large volume of images and written documents, an important criterion in Morgan’s selection of works is the materiality of fire. This includes works that use the element of fire in their creation, among them a series of ceramic sculptures by Gabriel Orozco titled Torso and Yves Klein’s “Fire Paintings” completed in 1961, the year before his death.

Room Two is based on consumerism and its material forms characteristic of Asian modernity. Plenty of space is allocated to Geng Jianyi’s mixed media installation Useless, comprised of a large collection of household goods. The curator states in her introduction: “The large-scale installation of Jianyi Geng, Useless (2004), marks the shift to an expendable consumer society in China and recalls the work of Song Dong, Waste Not (2005), shown in the 2006 Gwangju Biennale, which eulogized a previous generation’s precious relation to materiality.” Suknam Yun, born in Manchuria in 1939 and leader of the Women’s Art Society that grew out of the Minjung art movement, has created a work for modern Korean dancer Choi Seung Hee. This installation—largely made up of a collage of pictures of Yun dancing—traces her important position in the history of folk dance and modern dance in the region. In 1946, Choi Seung Hee went to Pyongyang in disguise to visit her husband; in 1967 she was branded a “revisionist of the capitalist class” and purged, after which she and her family were never heard from again.

After passing through a section based on touch and material, Room Three imagines and reconstructs the outward symbol of family—the home. Urs Fischer recreates his New York apartment for 38 E. 1st St (2014), in which the décor and furniture are meant to look as though they are made out of wallpaper. Although individual artists’ works could easily be lost against the background of Fischer’s colorful environment—three works by Heman Chong, for example, are placed together in Fischer’s study, including the performance piece Simultaneous—the viewer is invited to examine and contemplate Fischer’s role in this interpretation of the family. This space provides a bridge to explore the most relevant and immediate content of the exhibition in Room Four. Sex, gender, and subjectivity make up the core here, rehashing the identity politics and feminism of the Anglo-American school. Morgan made her name curating Roman Ondák’s solo show at the Tate, but amongst the several new works by Ondák, Clockwork seems more like a simple reproduction of Measuring the Universe (2007). This reveals the problem that most biennials face due to their ambitious scope and lack of resources: sufficient care is rarely taken in supervising the execution and maintenance of ongoing performance work. In the case of both Ondák’s work and Pierre Huyghe’s Name Announcer (2011) in Room Three, actors shrink from or ignore foreign visitors because of an inability to communicate in English, failing to actively welcome and greet them as requested by the artist.

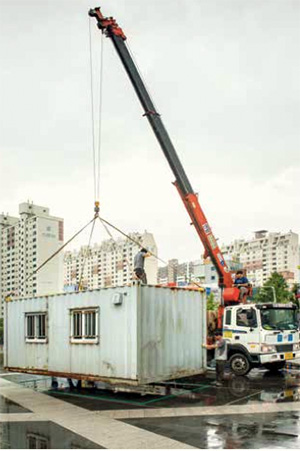

The exhibition ends with AA Bronson’s shamanist hut on a hill, one of only two pavilions built outside the main space, pervaded by the smell of herbal medicine and giving something of a hippie conclusion to the show. South Korea is one of the more developed democracies in Asia; using a cultural event like this one to continue to reflect on events in its pre-democratic political history is exemplary, yet what even more Korean citizens hope to find is the urgency of the present. On the opening night, young people gathered on the plaza clambered onto the roof of Minouk Lim’s shipping containers in Navigation ID (2014), not realizing that they contain the ashes of people massacred by the Syngman Rhee government during the Korean War. Like the high school girls mobbing Korean pop stars at the opening, these young people have lost any real connection with history and contemporary politics, expecting a biennial party more than a Biennale.