LIUXINYI: POLITICS OF KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICE

| 2015年01月21日 | 发表于 LEAP 30

TODAY, IT IS challenging to keep artistic practice and politics apart. With the shift from structuralism to biopolitics, philosophers and scholars have become obsessed with the subject. Jacques Rancière even believes that art is more important than politics, as art itself is a form of political practice. Meanwhile, Boris Groys points out that contemporary art is a system that operates for political mobilization and accumulation. The seventh Berlin Biennale in 2012, for example, shows that many artists now begin projects from their perspectives on daily routine, participatory practice, and other mechanisms of social construction. They have moved from their studios to social space and, consequently, regard galleries as a kind of political space that needs to be reassessed and transformed.

Inkjet print, labels, 160 x 160 cm

Compared to recent tendencies for art to act as a playground for political practice, the introduction of literary or documentary political elements into art can be traced back much further. For a long time, political images and symbols have been appropriated as ideological objects to be examined. Since Michel Foucault criticized narratives of history for their discursive power, cultural history has been dramatically diverted. When ideology collapses and political discourse is fragmented, it is replaced by personal, family, and community histories, and dissected as a cultural specimen.

Liu Xinyi’s work references the appropriation of historical symbols. One Night Back to Wartime (2014), made of 12 star-shaped navigation lights, is inspired by the artist’s research into 20 former socialist countries. Among them, nine have joined the European Union (EU), while three others are still waiting to join. These include eastern European countries such as the Czech Republic, Ro- mania, and Hungary; the Baltic States of the former Soviet Union; and Croatia, Slovenia, and other republics of the former Yugoslavia. At one point, each had its own national emblem with socialist implications. Considering their roles in today’s world, Liu arranges them into the emblem of the EU according to their political orientations.

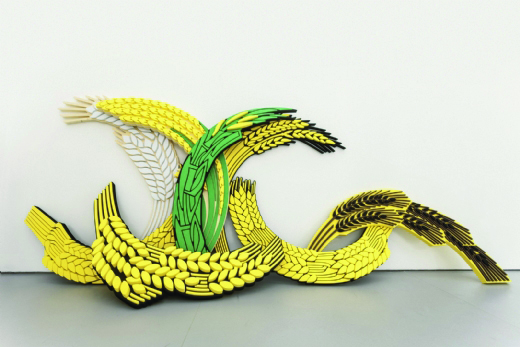

In Liu’s work, original political connotations are stripped away and political histories become raw materials to be recon- structed. Gems (2013), an installation first shown at Taikang Space, displays 11 types of colorful beverages representing the various Color Revolutions. Four were added later to enrich the visual experience of the work, corresponding to the Arab Spring then in process. Likewise, Whole Lot (2012) is derived from Liu’s curiosity as to whether the five-pointed star can shake off its sovereign con- notations. Reveling in the transformation of images with historical meaning, Liu’s Slippery Frequency (2010) uses a vacant local broad- cast channel to transmit his own commercials promoting tourism and investment in formerly communist countries.

Many of Liu’s works utilize text, commenting on the features of linguistic production. Both Universal Protest Banner (2010) and Don’t Forget to Vote (2013) directly employ text and language. Liu’s references often defy common sense and context, rendering them plausible illusions; their distinctive titles, however, give hints. We Have Friends All Over the World, for instance, is a slogan that originated during China’s unprecedented diplomatic isolation between 1958 and 1976, while One Night Back to Wartime comes from farmers’ complaints about fixed household output quotas at the beginning of the economic reforms of the late 1970s. Universal Protest Banner directly adopts all kinds of protest forms, such as red text on a white field. Liu not only cites texts, but also applies his knowledge to specific visual situations.

Plastic foam, dimensions variable

The production of knowledge must be connected to the knowledge system itself. Liu Xinyi’s textual logic consciously—or unconsciously—removes vague or ambiguous information, thus presenting a clear-cut narrative outline of the big picture. There is nothing ambiguous about Liu’s work. This neatness is reflected in his chosen visual language and subject matter, as with Cold War political symbols, geopolitical discourses, and the historical experiences of former socialist countries. Freed from their original ideological contexts, these materials are purified and made visually radiant, revealing their internal logics of transformation and reconstruction. Within the context of global exhibitions and visual experience, this approach avoids ambiguity to the maximum ex- tent, achieving visual communication with minimal losses.

Art is a space full of contradiction and conflict, no longer a linear representation of history, but rather a juxtaposition of historical clues. Here, history becomes an object of backtracking and rereading, making art production participatory, immediate, localized, confusing, and in constant flux. Participants of art production include everyone from artists to their audiences, as well as everyone along the entire chain of production in between. Today, art has become politics through the diverse experiences and possibilities it provides; as much as it must rely on the past, it can never be reduced to history.