STURTEVANT: DOUBLE TROUBLE

| January 27, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

PHOTO: Thomas Griesel. Courtesy of Estate Sturtevant, Paris

MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK

2014.11.09~2015.02.22

“If something is not yet known, then only what it is not can be understood,” wrote the artist Elaine Sturtevant—who preferred just Sturtevant professionally—in a 1971 letter. One of the most extraordinary and undervalued minds on the international art scene, the Ohio-born artist passed away earlier this spring, just shy of her 90th birthday and only months away from a retrospective of her 50-year career at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition is not intended as an elegy. Rather, it is curator Peter Eleey’s attempt to right the art historical wrong that a figure so present and so pervasive within the American canon might disappear so completely into it. After all, the long overdue retrospective is also Sturtevant’s first institutional show in the United States since 1973. This oversight would seem glaring (and, really, galling) if one were not familiar with the artist’s particular brand of hell-raising. Her work sits within the institution the way lit dynamite sits by the road in Wile E. Coyote cartoons; her technique of repeating (but not replicating) works by other artists calls the bluff in American modernism’s qualified embrace of the readymade, issuing a direct challenge to the cult of the authentic at the heart of most museums or collections of contemporary art. Ironically, in shunning the modernist dictum of innovation above all, Sturtevant produced some of the most radical work of the twentieth century. In truth, it’s to her testament that her legacy remains so uncomfortable for the contemporary institution.

Screenprint on paper, 95.5 x 51 cm. PHOTO: Arpad Dobriban

Courtesy of Estate Sturtevant, Paris, and Collection Thaddaeus

Ropac, Paris–Salzburg

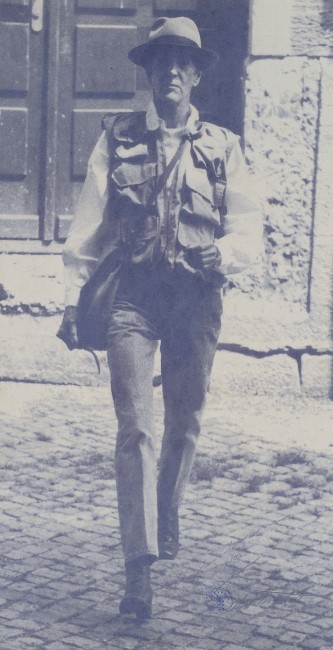

A survey of roughly 50 works dating from 1961 through 2014, “Double Trouble” sets up a paradigm for how to know, if not understand, Sturtevant’s practice. For starters, we are never left alone with Sturtevant herself; creative cross-dressing is grounded in the very first image, a portrait of the artist in the guise of Joseph Beuys hung at the start of a long corridor. The expanse of one wall is plastered with Sturtevant’s Warhol Cow Paper (1996), while the other is covered with a projection of Finite Infinite (2010), a looped nine-and-a-half-second video of a black dog galloping at breakneck speed across a field. The end of the hallway is anchored by Johns Target with Four Faces (study), a 1986 wall-mounted sculpture modeled after a Jasper Johns work, which, like the Warhol wallpaper, belongs to the series of what Sturtevant referred to as her “repetitions,” pieces that take on the same formal attributes and material properties as existing works by other artists, making the “radical leap from image to concept.”

While the notion of the original copy has held varied functions within international art history—from the educational purposes of academy training to the alternative art economy of the Dafen oil painting village—modernism’s advocacy of idea over execution paradoxically created a fetish for the authentic object. This leaves little space for intervention or interpretation, forcing artificial limits on the autonomy of a concept apart from the artist who first conceived it. Sturtevant seeks to break these limitations. Riling against the term “copy,” which would imply a mindless replication, she described her work as repetition, drawing parallels with other forms of art. In her mind, her take on Johns was no different than two pianists playing the same score. (“A Jasper Johns by Sturtevant,” she called it.) As Sturtevant saw it, American art history of the twentieth century presents itself as throttling along a vertical trajectory, accelerated by the capitalist doctrine of originality. What she offers with her repetitions is much needed “horizontal thinking.”

1985, sumi ink and acrylic on cloth, 25 x 32.5 cm

PHOTO: Prallen Allsten. Courtesy of Estate Sturtevant, Paris,

and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris–Salzburg

If Sturtevant intended her practice to be like reinterpreting a score, she gravitated towards artists who were already questioning the idea of authenticity. “Double Trouble” launches from the entry hallway with an entire gallery devoted to repetitions of works by Marcel Duchamp, an artist whose intelligence, irreverence, and fondness for alter egos makes his oeuvre a perfect foil for Sturtevant. Other frequent targets include Johns, with his stencils of commonplace symbols, numbers, and letters, and Warhol, with his silkscreens of readily available pop imagery. Sturtevant was also drawn to artists directly invested in doubling, appropriating either others’ works (such as Duchamp’s mischievous tweaking of paintings by Leonardo da Vinci and Lucas Cranach the Elder) or alternate identities: see Beuys, who paraded as notorious gangster John Dillinger, or Paul McCarthy, with his acidic impression of Willem de Kooning as a clown. Sturtevant often assumed not only the appearance of these works, but also the process. For her rendition of Warhol’s “Flowers,” made just months after his, Sturtevant used Warhol’s own screens; the final products are nearly indistinguishable. When Sturtevant could not find the exact screen she had in mind for a Marilyn Diptych (1962), she tracked down the original publicity shot of the actress, which she then brought to the same craftsman who produced Warhol’s silkscreens. In this sense, it was Warhol the artist—not the work—that Sturtevant was doubling.

2014, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

PHOTO: Thomas Griesel

Courtesy of Estate Sturtevant, Paris

The juxtaposition of these pieces provides powerful punctuation in and of itself, but the exhibition pushes further, injecting a selection of work into the permanent collection’s gallery of Dadaists. This is where the double truly causes trouble. Sturtevant’s objects infiltrate the gallery with a sickly ease. After all, the objects on display—particularly Duchamp’s readymades— aren’t even originals in the art historical sense. The Bicycle Wheel, for instance, is a third edition from 1951, to replace the 1913 original. Sturtevant made her own Bicycle Wheel in 1969, which Eleey could have installed as a surrogate; his choice to show Sturtevant’s Duchamp Trébuchet (1997), a color photograph of a coat rack enhanced with gauche, and thus directly invested with the artist’s hand, keeps the conversation from veering into a debunking of the readymade. While elegant, the gesture does not get much mileage.

In some ways at home in the Dada gallery, Sturtevant’s work shouldn’t be. After all, the whole purpose of horizontal thinking is to disrupt this kind of trajectory, to prevent a reading of the art of the American twentieth century as a progression of finite events, a trail of cause and effect that preferences innovation over interpretation. “I create vertigo,” Sturtevant proudly claimed, describing her exquisite art historical dislocation as the “perverse simultaneous double trouble of being ahead and being behind.” This sensation would later be codified by the postmodernist discourse of the 1980s, but, as “Double Trouble” shows, the contemporary museum still isn’t quite sure how to handle Sturtevant. Let this retrospective be an opportunity for reacquaintance; the understanding can come later.