WANG JIANWEI: TIME TEMPLE

| January 21, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

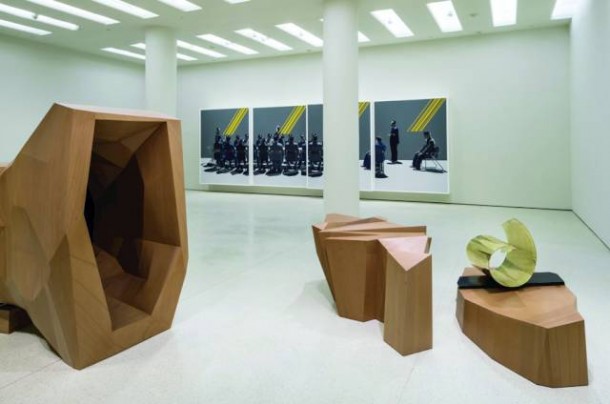

PHOTO: David Heald. Courtesy of the artist and Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum, New York

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK

2014.10.31~2015.02.16

How much meaning can be read into the presentation of a single solo exhibition? Much has been made of the fact that Wang Jianwei’s exhibition at the Guggenheim is the first such major museum solo for a Chinese artist; while the viability of this claim depends entirely on how the variables “major” and “Chinese” are defined, the broader narrative at stake here is a shift in the tools used to understand art from China at the global level, from the survey-based “China show” to individual voices and practices. In the context of the Guggenheim, perhaps the implication here is that the Cai Guo-Qiang retrospective of 2008—sponsored by the same Robert H. N. Ho Foundation that funds the grant series behind this exhibition—was more a China show than an institutional solo show.

Nevertheless, we no longer live in a time where the very idea of a New York museum exhibition of a relatively senior Beijing-based artist is a novel concept. The fact that it happens with such rarity might be more surprising. The more interesting question would be why Wang Jianwei, whose practice belongs to such a specific moment in contemporary art history, emerging first as a painter in the 1980s and then, more significantly, with experimental video projects around the mid-1990s. Thomas Berghuis, curator of the exhibition, is known primarily for his scholarship around the question of liveness during this period, culminating in the seminal book Performance Art in China.

For Wang Jianwei, concepts of theatricality have dominated the evolution of his practice, beginning with the early experiments of videos like Production, in which seemingly scripted lines are drawn from ordinary social conversations in public spaces, and Living Elsewhere, which follows the everyday choreography of a group of rural poor living in abandoned luxury housing. He has been continually fascinated by ideas like rehearsal, a mode of doing without doing in a final sense, and instability, as with the sense of moving without progress that belongs to the yellow signal at a traffic light. If precarity and process are Wang’s motivating keywords, these come through in part in the film The Morning Time Disappeared, a transplantation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis into the old city of Beijing (the cockroach is replaced with a mermaid-manatee hybrid of some kind).

Wang Jianwei has recently returned to painting practice, and in a way not dissimilar to his conceptual approach in the opening years of his career. Several such canvases make their way into “Time Temple,” including a major four-panel piece sharing a title with the exhibition itself and depicting a barebones boardroom of some kind, like a mid-level cadre meeting in some corner of the state apparatus. Wang does a very honest thing by including these paintings and an identically titled series of abstract sculptures based on the spatial analysis of the forms of his practice: his core interests might be with process and production, but he has never stopped making things. At the end of the day, however, none of them matter as much individually as the ideas that give them shape.

Reflecting a confidence in the practice of the artist over these kinds of discourse, “Time Temple” leans heavily on form and aesthetic, bringing together quite a few strands: the social documentation and engineering of the film, the realist imagination of the painting, the abstract machinery of the sculpture, the auteurial directorship of the as yet unfinished performance Spiral Ramp Library. Viewers who have followed Wang Jianwei’s work in Beijing will be surprised at the lack of theoretical discourse offered around these projects; perhaps it was assumed that the artist’s often contrarian readings of philosophy would be received less amenably in New York. Similarly, his sprawling multimedia performances—incorporating live, static, and digital elements—are left out of a presentation that, ultimately, appears just a little bit too neat and tidy.

In its aesthetic, the resulting set of objects and images appears very much of Beijing in this moment: rough materials, clean lines, a touch of post-socialist realism. If Wang Jianwei’s individual voice seems ground down every so slightly, his project is an accurate portrait of the ideas and ways of working circulating around his peer group right now. Tellingly, the casual visitor to the Guggenheim this fall could wander from the adjacent Zero group retrospective into and out of Wang’s exhibition without recognizing a firm boundary between the two; Wang has incoporated a similar set of ideas around technology and temporality, but this is not the extent of what he has to offer.