ART IN THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

| March 27, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

TRANSLATION / Daniel Nieh

THE PRODUCTIVE ENVIRONMENT

“Consumption, as a necessity and as a need, is itself an intrinsic aspect of productive activity.” ——Karl Marx, Economic Manuscript of 1857-1858(1)

The word “production” has a positive connotation in terms of artistic practice, referring to the generative state of interaction between various possibilities for critiquing conventional thinking. This understanding, specific to the art world, stands in contrast to the common conception of production as goal-oriented, standardized, and large-scale.

The contemporary city is a massive machine that produces knowledge, power, and desire. Theory, including criticism of the art system, unfolds its critique of consumption primarily from the perspectives of sociology, anthropology, and everyday life, because the arguments of Marxist thinking emphasize the decisive effects of production on consumption. When dramatic changes affect the environment of production, the effects of consumption and the responses of the production process are overlooked. With critical theory flourishing, we must return to the links of production and use the methods of historical ontogeny to examine the generation of knowledge, power, and desire.

Wang Jianwei’s Production (1996) is usually understood as a documentary about a teahouse. In fact, the teahouse in Anrenzhen is actually a cultural center run by the local government. Wang’s goal in filming this particular place was not to portray the survival of old ways of life in the context of urbanization, but rather to visit a place where people gather instinctively. The more quotidian the circumstances, the more effective the exercise of biopolitical authority.

The first time Wang Jianwei brought his camera to the teahouse, he was immediately equipped to observe dialogue among its patrons. Naturally, the most prolific speakers quickly get thirsty, and listeners have the habit of buying them more tea, a completely normal part of tea culture. The less someone has to say, the more he or she is penalized, both materially and psychologically. Of course, sometimes such customers manage to squeeze out a few lines to demonstrate that they aren’t completely lacking in merit. Speaking, listening, paying—as long as you can speak, regardless of whether your opinion is considered or not, you can momentarily control the conversation. As Wang sees it, the place was more than an innocent teahouse, and its dynamics deserve exploration. Patrons, whether they are ordinary people or party cadres, share a material and psychological consensus regarding discursive power. It is this normalized, tacit, oppressive power that the artist is interested in revealing. Making it possible to see, feel, and weigh this dynamic is a test of his ability to creatively respond to society.

Asked why he chose to film a teahouse in a county town rather than one in the city of Chengdu, Wang Jianwei says that, if he were to shoot in an urban teahouse with clear commercial and recreational functions, the project would rapidly be co-opted by the explicit spatial characteristics of the location. There is more room to work in a less clearly defined gathering place. However, even this diligent consideration of the production environment proves to be limited by the conditions of reality.

Wang Jianwei also filmed the demolition of Guanyin Alley in Chengdu in the 1990s. He was only able to freely shoot the subjects he was interested in by leveraging personal relationships to receive approval from grassroots cadres. When he filmed a dispute that took place at the offices of a dating service, he had to win the trust of the involved parties, which goes to show that an artist’s work is only possible under conditions of consensus. The implication is that concessions to authority are difficult to avoid from the outset, regardless of whether or not the presumptive controller of discursive power has the upper hand in a specific situation. As long as an artist orients his or her work in concert with biopolitics, it is existentially entangled with the shadows of self-contradiction. In the end, Wang stopped making documentary films.

Escaping these restrictions requires the use of imaginative means to express the unverifiable—and, in particular, those unverifiable things that do not yet exist. That is to say, one must go beyond questions of how to begin production or what direction to explore in order to address the far more important problem of how the conditions of artistic practice are created. The key is to experiment with the creation of environments conducive to production.

THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

Today, the exhibition and commerce of art can inhibit creativity in ways that dissatisfy artists. Polit-Sheer-Form, a ten-year-old collective of five artists intended to foster mutual benefit, and “Unlived by What is Seen,” a large-scale group show, proclaim their withdrawal from the curatorial system but still leave the artist at the mercy of the consumer. These critical and reflective approaches struggle to escape a fundamental paradox: if one does not consciously weaken the intentionality of an artistic practice and limit its scope, then the risk of creating new discourses of power is unavoidable. On the other hand, interdisciplinary exchange generally lacks the proper fundamental conditions of sharing; relevant knowledge and experience originate within disciplinary frameworks partitioned long ago.

In 2014, Floor #2 Press initiated “5+1,” a program intended to use the area between Beijing’s fifth and sixth ring roads as a shared backdrop and working location for practitioners from various fields. The area is home to a swath of suburban villages that face the encroachments of urban sprawl and the looming possibility of demolition. In 2013, LEAP covered the work of migrant worker communities in this area. The Culture and Arts Museum of Migrant Workers and the movement known as New Worker art blend social movements, historical discourse, economics, and education in order to benefit marginal communities. Contemporary art is just one of the fields mobilized to fuel the public debate. A practice that creates connections within society can only avoid institutional resistance and achieve resonance if it is not absorbed within the discourse of a single field.

The urban environment is a realm of constructed problems and discourses, a junction of history and various disciplines. It also provides a fresh context for pre-existing issues, including the urban state of contemporary art and practices that have been constrained or abandoned by mainstream discourse.

ART IN THE CITY

A city’s allocation of usable space determines whether or not a given social practice possesses ideological legitimacy. The creation of contemporary art is intrinsically linked to exhibition space. All sorts of experiments subvert the dominance of traditional, studio-based working methods, but works of art cannot be completed if there is nowhere for them to be exhibited. As a consequence, the underground status of contemporary art exhibitions in the 1990s placed extreme constraints on creative channels. Of course, it also catalyzed the creation of uninhibited new works and forms of exhibition.

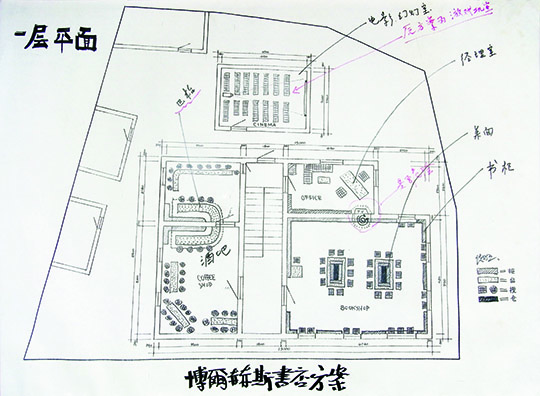

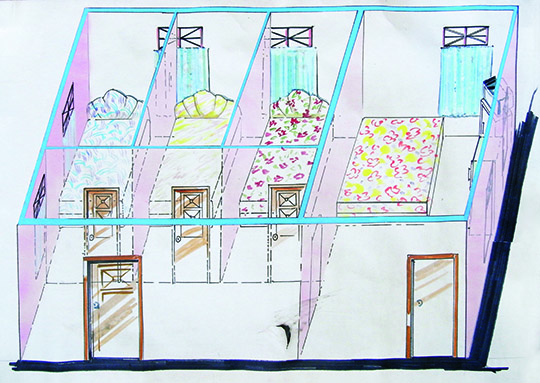

In 1994, the artist Xu Tan created The Alterations and Extensions of No. 14 Sanyu Rd., Guangzhou in a building slated for commercial renovation. He submitted two proposals for future use to the landlord—a bookstore and a brothel with a hair salon front—and used the temporary space to exhibit the proposed blueprints, renderings, a mattress, various objects, and a video explanation for the landlord. At the time, hair salon brothels were common in Guangzhou, and one of Xu’s friends had opened a bookstore, so Xu felt both proposals were realistic. The project demonstrates his preoccupations at the time: exploring the extent to which he could combine artistic practice with his personal experience of urban life.

The horizontal links formed by the work of artists may often be created aimlessly or unintentionally, but they nonetheless lead to an art historical discourse that yields insight into the coagulation of the urban environment.

In 1999, a group of dynamic young artists organized an exhibition at Shanghai Square, a shopping center on Huaihai Middle Road. The mall was growing in popularity as the area underwent redevelopment in the mid-1990s. The artists held their exhibition, “Art for Sale,” in two conjoined spaces on the mall’s unoccupied fourth floor: an unfinished retail space and a supermarket that had yet to open its doors. The audience had to enter through a supermarket in order to access the main exhibition space. These were the rules of the game: participating artists had to create one set of works for the gallery and another set for the supermarket shelves; the latter had to be mass-produced and sold at a low price. The vast majority of visitors saw this unexpected encounter with contemporary art in a shopping mall as interesting and entertaining. Although the exhibition was forced to close after three days, the supermarket still managed to rake in more than RMB 10,000, and received a great deal of negative coverage from media outlets including the Xinmin Evening News. Remarkably, by 2004, the Oriental Morning Post and several other mass media outlets were willing to establish formal ties with these artists. That year, the same artists were working on another project, “Dial 62761232 (Express Delivery Exhibition),” which involved placing advertisements in mass media outlets. By calling the number, one could arrange to have the works in the show brought to a given location and exhibited one-by-one by the delivery person. The Oriental Morning Post was more than willing to collaborate; it even asked to participate in the exhibition as an artist. (The project organizers refused, in the end only allowing a reporter from the paper to participate as an individual.) For this project, mass media was a necessary component of the curatorial process, not merely a tool of dissemination.

In terms of urban spatial planning, some may describe contemporary art as underground, but the parameters of urban development and renewal have provided ample temporary vacant commercial space for exhibitions. Even new industries like delivery services have become elements of efforts to entwine exhibitions with everyday life. Mass media is both a product of the city and a direct contributor to urban culture. The scathing critique of the Xinmin Evening News in 1999 and the enthusiastic participation of the Oriental Morning Post in 2004 demonstrate the roles played by mass media in shaping contemporary art. Today, the K11 Art Mall, another contemporary art project on Huaihai Road, seeks to utilize mass media and contemporary art to express the relationship between aesthetics and fashionable shopping. We have come a long way since Shanghai Square.

Xu Zhen, one of the curators of the “62761232” exhibition, states in an interview, “We hope to use this exhibition to understand what kind of role contemporary art plays in this city, Shanghai. In a social environment that idealizes economic development, is contemporary art something that this city needs?” The relationship between artistic practice and the urban environment has progressed from one of spatial limitation to assimilation into the urban mechanisms of production—and, ultimately, the construction of new restrictive relationships. Now that the Shanghai Biennale and 798 have both received official sanction, the exhibition spaces of China’s major cities have finally been consecrated. There is, of course, a tremendous influence on the forms and work methods employed by artists.

The rise and fall of social critique and resistance in contemporary art in China and elsewhere are part and parcel of the historical processes of change that characterize urban environments. Contemporary art risks being consumed as part of the urban spectacle; at the same time, the urban environment also generates new discursive spaces in which pressing issues might be addressed.

(1) The Complete Works of Marx and Engels, vol. 30, People’s Press, 1995, p. 35.