HITO STEYERL: TOO MUCH WORLD

| March 28, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

IMA BRISBANE

2014.12.13~2015.03.22

Although Berlin-based writer and artist Hito Steyerl’s films are not often seen in the Asia-Pacific, her name was frequently invoked in Australia around the time of the 2014 Biennale of Sydney. In Is a Museum a Battlefield?, a performance-lecture at the 2013 Istanbul Biennial, she highlighted sponsors’ links to the militarized policing of the city. Subsequently edited into a 36-minute film, it was discussed as evidence that, in the art world, following the money always leads somewhere unpleasant, dirty, or even bloody, while Steyerl’s embedded, symbolic response was contrasted with the direct action of an artist-led boycott that ultimately forced the resignation of Biennale of Sydney chairman Luca Belgiorno-Nettis and the removal of principal sponsor Transfield due to its role in running offshore detention centers housing asylum seekers. Is a Museum a Battlefield? is not included in “Too Much World,” the first Australian survey of Steyerl’s work, but it provides the background to the show by encapsulating her artistic concerns with the way things circulate in our densely interconnected world.

Guards (2012), the first video installation in the IMA’s main exhibition space, stresses that the museum is always a battlefield. Steyerl works between documentary, with its conflicted relationship to truth, and the cognitive leaps and associative logic of the essayistic mode. At least superficially, Guards tends toward the documentary end of this spectrum, presenting seemingly straightforward testimony from two former law enforcement officers working as security guards in art museums. The two men explain how they police the architecture of the white cube in a single-channel HD-video film simultaneously screened on two monitors to elicit viewer movement and an awareness of bodily space that is reflected in the work.

The architectural context of her work has become increasingly important to Steyerl in recent years. She now works with Berlin’s multidisciplinary Studio Miessen on all her exhibition designs. In Brisbane, the results are extremely satisfying, complementing the ideas of the individual works and pushing Steyerl’s explorations of porous networks that spill beyond singular screens. “The all-out internet condition is not an interface but an environment,” Steyerl writes; the internet, she says, has actually moved offline.

This permeation of physical and digital, Steyerl’s major theme, is clearly evident in the two works at the center of the exhibition, Liquidity Inc. (2014) and How Not to Be Seen. A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013). Among other helpful suggestions, the latter playfully proposes that we, as physical bodies, might consider becoming smaller than a pixel if we wish to evade the all-seeing surveillance that has become the defining feature of our existence. In Liquidity Inc., shown in a viewing environment with a wave-like half-pipe and bean bags, the liquidity of financial trading is aligned with speculations on the weather: global financial crisis as tsunami.

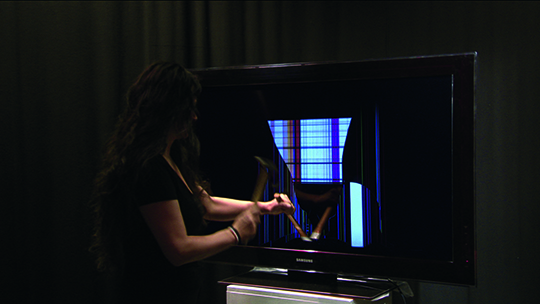

The rest of the exhibition shares overlapping interests in abstraction and political revolution. Titled after a Sergei Eisenstein film, Strike (2010) presents a short, sharp shock: in a 25-second film, Steyerl attacks a flat-screen monitor with a hammer and chisel, drawing attention to the image’s material substructure. A homage to Russian constructivism, Red Alert (2007) is a monochromatic triptych of red screens modeled on color-coded levels of terrorist threat. Finally, as if providing anachronistic commentary on the events in Sydney and Istanbul, Adorno’s Grey (2012) juxtaposes the apocryphal story of the Frankfurt School critical theorist Theodor Adorno having his lecture theater painted gray with that of a 1969 incident in which three female students bared their breasts to him as part of the ongoing protest movement of that radical moment. Adorno, who was not a fan of direct action, died of a heart attack not long after.

Dylan Rainforth