COMMUNITIES OF KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION

| May 21, 2015 | Post In LEAP 32

The Beijing art world likes talking to itself and about itself. When the word “Beijing” is part of a seminar title, it does not describe a geographical area, but implies a certain grandness of theme, density of conferences, and efficiency of discourse. Today, whether it’s a panel organized by an institution or an impromptu artist’s speech, they are all byproducts of the power of criticism.

Since the be ginning of the twentieth century, the relationship between art and knowledge has grown more intimate, as art—in practice and theory—has become systematized, institutionalized, and conceptualized. Over time, processes that had once been peripheral—exhibition and curatorial practice, media dissemination, and the narrative history of art—became essential elements of this system, a part of art itself. Today, knowledge production has become the form of art practice in vogue. In China, the increasing irrelevance of independent criticism stems from changes to the art system, and constructive participation in conversation comes to replace the role of the art critic. Take “Ho Chi Minh Trail” (2010): organized by Long March Space, the project combined field research with academic discourse, inviting artists, curators, and scholars to engage in conversations that stretched across China and southeast Asia, including Lu Jie, Gao Shiming, Lu Xinghua, Wang Jiahao, Xu Zhen, Liu Wei, Zhang Hui, Dinh Q. Le, and Nguyen Nhu Huy.

Five years on, participant Wang Jianwei notes that “Ho Chi Minh” affected the subsequent artistic evolution of everyone involved. Wang says that his 2011 solo exhibition at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, “Yellow Signal,” grew directly out of discussions during the project—it was forcibly pressed out during a compulsory conversation. Consciously or not, Wang’s thinking and practice since his involvement on the Trail have been connected to discussions from 2010. Consequently, he has sought opportunities and discursive contexts similar to what the project provided.

Xu Zhen, another participant in the project, says that he did not have much hope for real dialogue when he joined the project, but he soon discovered that effective conversation was possible as far as artists and scholars were asking similar questions and using similar methods of inquiry. Returning to Shanghai, Xu marshaled support from MadeIn Company and encouraged Jin Feng to organize the “Future to Come” project, a series of weekly conversations and discussions that has continued for nearly four years. Topics have included art, philosophy, politics, history, and many others, drawing on artists Yang Zhenzhong, Zhou Xiaohu, Shi Qing, and Zhang Ding. The project has also hosted Boris Groys and Jacques Rancière for lectures and thematic discussions. Then, in 2014, Shi Qing created Radical Space, a long-term project that hosts smallscale symposia and conversations at irregular intervals, a continuation of the conversation as artistic practice.

Projects such as the Bali Conversations and Shen Ruijun’s 2012 exhibition project “Pulse Reaction” at Times Museum function as conversations that occur within a self-satisfied art system. While philosophy and politics directly overlap with art, other disciplines—medicine, ethics, and law—lack direct connections with the discipline. When art turns toward these fields, the motive is not to accept them as examples but rather to trace their paths in the hope of being exposed to new ways of seeing and examining the world. Therefore, the premise of these conversations is generally not practicality or mimicry, but rapport. Success is not important; knowledge production has become art.

At the end of 2014, philosophy scholar and editor Wang Min’an organized the symposium “Michel Foucault in China,” which took place at Red Brick Art Museum. Discussions centered around Foucault’s influence on philosophy, politics, ethics, and art. The symposium attracted artists, critics, and curators, inspiring widespread attention in the art world—a response due not to the fact that the symposium was held in an art museum, but due to the ways that Foucault’s thought has affected contemporary discourse.

Today, conferences in Beijing’s art world are isolated and sporadic; there are few long-term structures that encourage rigorous thinking and extensive conversations. One such project, West Heavens, organized by Chen Kuan-Hsin, Johnson Chang, and Gao Shiming, has been able to sustain research and discussion around this phenomenon. To achieve consistency depends on a set of systematic guarantees that lose contact with the reality of the art world as social, political and ideological currents evolve.

From 2005 to 2010, Huang Zhuan organized a series of discussions at OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT) around art history and the history of ideas in attempt to construct parallel relationships between artists and intellectuals. He sees that conditions are far from ideal, and effective interdisciplinary discussions are difficult to initiate. In Huang’s positioning of OCAT Beijing, he limits the frame of reference to art history, the goal being not to build a hermetic knowledge system, but rather to use its apparatus as a starting point to formulate an art historical knowledge paradigm through dialogue with religion, philosophy, archeology, politics, linguistics, psychology, and anthropology—what Aby Warburg called the “synchrony” of civilization. Starting in 2014, Huang and his team have focused on the translation and compilation of western art history’s evolution.

Although these rather traditional methods of dialogue persevere, the current reality is such that, aside from conducting ritual discussions of art in public education or the media, the preferred mode of communication is digital, via applications like WeChat. It is not that the conversation has ended due to the absence of ritual, but rather that new, temporary, and ever-changing communities are gradually replacing older forms of art and knowledge. When the art practice of knowledge production becomes mainstream, it will mean the transfer of power away from a certain set of artists; the question is then how to rebuild the identity of the artist.

TRANSLATION: Jiajing Liu

A CONVERSATIONAL APPENDIX

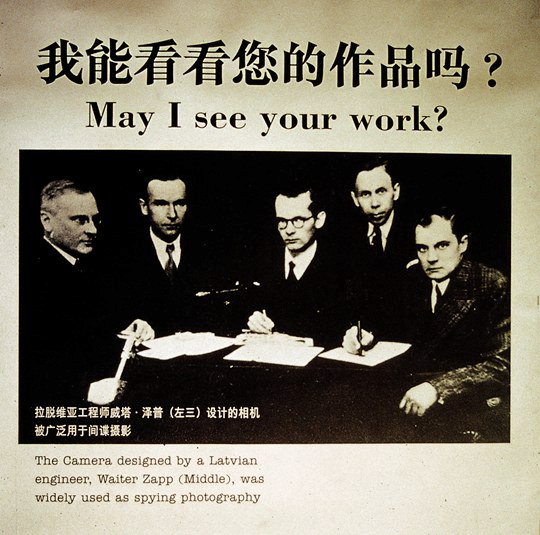

In his 2008 work Conversation , artist Liu Wei interviews friends from the Beijing cultural scene. In these artist-led discussions, he touches upon his peers’ thoughts on discussion, artistic exchange, and connections between art and the public interest.

Liu Wei: I’m very happy to have the opportunity to speak with you. Can I ask you—how do you feel about interviews?

Chu Yun: As a form of self-expression, they’re a bit like wrestling.

LW: An interview has two aspects: one aspect is conveying the truth to other people. The other aspect is expressing something not so true, demonstrating something for the sake of others. How do you feel about that?

CY: I feel expressing the truth is basically impossible. It’s a kind of performance.

LW: If everyone knows that this is a performance, then how are we to proceed? Is there any point?

CY: If everyone pretends that true self-expression is possible, and then advances an exchange, it seems like we can discover the truth. I have a viewpoint on interviews, at least when it comes to myself. They are close to a kind of truth that we have fabricated, but their authenticity lies in the event of the interview itself and nothing more.

***

LW: Were you a conscientious student? Do you think about problems consciously?

Yang Mian: I think I was more conscientious as a student than I am now. The Sichuan Fine Arts Institute was a small scene. There weren’t many people to hang out with in Chongqing. If you had dreams of creating art, you could often find people to talk to, who turned from friends with common dreams to friends from school, and then eventually into fair-weather friends.

LW: It can end up that way. Everyone talks about their studies until they eventually get bored of it. But, as they continue to meet up again and again, they stop talking about their studies, and become something else.

YM: If I’m with you every day and know your every thought, what’s the point in talking?

LW: There also aren’t that many things to talk about in the academy.

YM: And many you just can’t grasp, the kind that you want to hide deep in your heart and work on silently. Art is extremely personal. If you want to participate in it, you can. Artists don’t really make their own conclusions … if their artistic systems are sound, artists don’t need to make conclusions. There is someone to make conclusions for you. You just need to draw attention to the imperfect, incorrect things in your system. I think the artist who draws attention to correct things is something of an idiot.

***

LW: I still prefer to interact with curators. Perhaps this comes from my work itself.

Wang Wei: Where do you think this interaction is necessary?

LW: Sometimes it expands on areas I didn’t expect. The majority of my works are put on display in exhibitions, and the process of this exchange allows me to make some of my own ideas more distinct.

WW: Before, when I was working would ask people, “What do you think of this idea?” But now I feel that no one can help. This is a very personal thing. It has nothing to do with anyone else. The things I talk about are quite superficial. They’re not born of deep reflection. I’m not convinced that everyone can talk about these things. Of course the exchange of ideas is necessary, but talking specifically about art is completely impossible. Do you feel that being an artist brings about feelings of loneliness? It’s so solitary.

Not like filmmaking, which has a social aspect. It can be communicated. Artists are precisely the opposite. Art is something that one makes for oneself. Even if now it has been thoroughly socialized, its personal nature remains.

***

LW: Jiechang, you’ve stayed in Europe for a number of years. How has your identity changed?

Yang Jiechang: My 20 years in Europe have been pretty significant. I’ve seen a lot, and experienced a lot of particularly disturbing things, but, more specifically, the fact is that my family is European. The Europe or the China that they have experienced is not the Europe or China that we can imagine. I like to take these specific details and put them in perspective.

LW: The things you’ve done, like the Eurasian flag, or the Pearl River Delta—what is the basic idea behind them?

YJ: Recently I saw a discussion at the British Royal Astronomical Society, which said that humanity still thinks in terms of European tribalism, and that immediately resonated with me. No matter whether it’s Guangzhou or Beijing, or Europe or America, from an astronomer’s point of view, they’re all as small as a grain of sand. If we could borrow that vantage point, things could really open up. Looking at the bigger picture, the possibility of communication grows exponentially.

***

YM: Material life and culture in China are particularly good, but the quality of cultural life is lacking to the point that I often feel superior to uncultured people, because the largest part of our time is still spent enjoying relatively homogenous cultural resources.

In these circumstances, our consumption of culture always lagging behind. The things we collect are cast-offs from others with standards that have already been set, so there’s no need for us to set our own. In film, television, and literature, everything is like this. China has become the world’s biggest translation factory, and whoever is translated the most becomes the most important and the most complacent. If we can produce our own work at the same time—representing not what is popular, but only what is individual—we will eventually see a more robust society.

***

LW: What do you see as the differences between fashion and art circles and other industries?

Zhang Dan: I think fashion is just a very small part of life. I’m interested in it is because it’s a part of life tied to aesthetics, and its practical applications can be powerful. It’s a kind of creativity that can be consumed. It has its basis in two points: one, it must be consumable; two, its beauty must be creative aesthetics, a kind of ingenuity towards beauty. Then, by breaking down this thing, it can be consumed by the masses.

LW: And art?

ZD: Aesthetics are just one part of art. I think art is connected to humanity. There is fear, anger, sorrow, joy, and so on. It can have nothing to do with aesthetics at all.

LW: Of course there is the question of aesthetics in artistic circles, but not as much as in more popular media like film and television.

ZD: Popular aesthetics can be more narrow-minded, but it also has a more direct connection to physical human life.

LW: A connection to life itself?

ZD: Of course it also has an educational element.

LW: But I feel it isn’t really connected to life. It’s just a guide. It doesn’t stem from physiological needs or anything of the sort.

***

LW: In the system we have now, what are the issues facing art in China or in the world?

CY: Saying “system” is too academic. In fact, what we are facing is a global art corporation. But this is changing now too, and new possibilities may emerge. It’s a question of time. The corporation is a relatively advanced kind of structure. It can change many things and create a lot of value, but, when it comes to being an artist, we can also investigate other sorts of issues.

TRANSLATION: David East