THE RULES OF ATTRACTION WITH TIMUR SI-QIN

| May 12, 2015 | Post In LEAP 32

View of “Premier Machinic Funerary: Part II,” 2014, Carl Kostyál, London

Courtesy the artist and Société, Berlin

Artist Timur Si-Qin unveils his first solo exhibition in China, “Biogenic Mineral,” at Magician Space in April 2015. For this exhibition, the artist presents the brand Truth by Peace (TBP) in sculpture and photography. LEAP talks to Si-Qin about attractors and their varying forms in his work.

LEAP Your work frequently makes use of commercial imagery and products, but you’re less interested in an ideological or psychoanalytic perspective on these cultural entities than in their materialist realities—their biologically conditioned behaviors and the roots of attraction. You’ve been associated with the contemporary philosophical movement of new materialism. Is that the intellectual framework for your work?

TIMUR SI-QIN Yes, I was very much inspired by the writings of new realists such as Quentin Meillasoux, Levi Bryant, and especially the brilliant philosopher and shaman Manuel DeLanda, with whom I published an interview with a few years back.

Carl Kostyál, London

Courtesy the artist and Société, Berlin

LEAP And this realist-materialist position you’re taking is by no means an antithesis to the cultural theories so dominant in our generation?

TSQ Right. It’s not that I’m not interested in or don’t believe in the power that ideology holds over the world. But I don’t think it’s the whole story. I think Levi Bryant says it best, when he tries to “draw attention to the material dimensions of how we dwell and live. Today, more than ever, we need to ref lect on whether the tools of deconstruction, phenomenology, psychoanalysis, Marxist critical theory, and semiotics are adequate to thinking the world we dwell in and how these theoretical orientations might erase the fundamental materiality of existence … We need a form of theory capable of thinking that and that avoids the urge to treat everything as texts, meanings, and correlates of intentions.” Meaning is not the entirety of being.

LEAP How do you think this realist movement influences art production?

TSQ The way so much art and art criticism functions now is through this psychoanalytic model, where you produce a certain set of signs and then it’s up to the critic to analyze them and attribute them to some sort of consciousness that might not even be the artist’s. I think this model is too susceptible to a kind of pareidolia, seeing faces where there might not be any. Evolutionarily we have this propensity to identify something as consciousness out of self-protection. Similarly with capitalism: so much art writing today takes the form of psychoanalyzing capitalism, to the point that everything can be attributed to capitalism, with no real investigation whether there is an actual causal link or what that is actually linking to.

mixed media, printed perspex, metal,resin, LED, 285 x 195 x 171 cm

View of “Biogenic Mineral,” 2015, Magician Space, Beijing

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

LEAP Frequently it’s not the link that is missing, but what is being linked to. People often have very ill-informed ideas about capitalism and like to ascribe everything to this one banner, as if it’s the only relevant governing force of our existence.

TSQ The same applies to a cultural lens. When there’s a real person whose arbitrary experiences and associations produce the work, there’s no actual causal link where you can say this painting is the direct result of a certain culture. I think maybe new materialism could lead more artists to question how and why images work the way that they do. Beyond them simply being culturally coded symbols, what are the material dimensions by which they function, or what is the material context that makes culture code them this way in the first place? This is why advertising is so interesting to me, because its whole business is to understand these things, like the fact that shiny and reflective images are favored because of their subconscious connection to water, or the fact that people will prefer an image simply because it’s brighter. I think simply being aware of these dimensions offers a small emancipation of free will.

Courtesy the artist and Société, Berlin

PHOTO: Simon Vogel

LEAP Right. Your work with commercial objects and imagery highlights this biological layer that constructs our commercial and cultural landscape. Let’s talk about your own construct of this seemingly commercial entity: the PEACE brand with a yin-yang symbol. How did you come up with it?

TSQ The PEACE brand came out of thinking about the materiality of images. Obviously the use of brands has a material effect on the world in that they cover almost all surfaces these days. To many this is a frightening encroachment of ideology, but I don’t think that’s the explanation for their existence. Brands have spread all over the world simply because of the way they access the brain and are stored in our memory, regardless of ideology or culture. On top of this, I’m interested in how modularity and plasticity are intrinsic to the world. Things can be used as things other than what they were predestined for. In biology this is called exaptation, when a trait evolves for one thing but ends up being used for another. For example, how dinosaurs evolved feathers initially for heat regulation but then eventually were able to fly with them. I think this is an insight into the freedom of our contingent reality and deconstructs the notion that biology is predetermined and immutable. I think this comes close to the buddhist notion of emptiness, in that nothing has an immutable essence. In developing the brand, I’m interested in using symbols this way. Combining disparate symbols, stripping them of much of their original meaning and repurposing them in a new way. In a way, I’m thinking about it metallurgically, treating the symbol in various ways to extract new material behaviors.

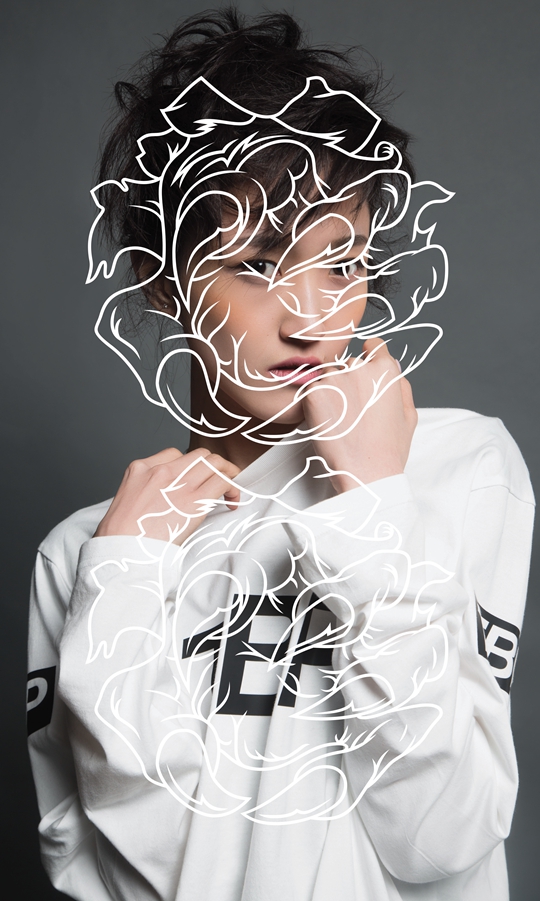

LEAP What’s the idea behind Truth by Peace (TBP), the brand you created particularly for this show in Beijing?

TSQ The brand is designed as a knock off of Hood by Air, or a play on that. It goes back to the idea of taking a word and stripping it of its meaning. What I like about Hood by Air is that it’s just two very distinct words with no real associations. With Truth by Peace, I wanted this vague pop image—a hip-hop or K-pop look. The logo is based on an illustration I found on iStock. It serves as a general symbol of street style, Monster Energy, and so on. Its octagonal shape corresponds to that of a sculpture in the exhibition, which is a play on traditional Chinese landscaping.

LEAP The visual elements in this show are quite new to your practice. How did you arrive at these forms for this show?

TSQ The show I did in 2013, “Basin of Attraction,” was a first step for me to identify image attractors. But what constitutes an attractor can get very elaborate, much stranger than just stripped-down elements. Like Hood by Air, for example: it’s registered as something really attractive, and so are traditional cultural motifs. So in the new work, I’m trying to expand this idea of the attractor and show that it can apply to many things beyond the cold and sterile aesthetic I started out with.

LEAP Those earlier pieces relied on a pretty straightforward formula. The use of stock images emphatically calls attention to the underlying patterns and algorithms of commercial imagery. With this show, it seems like the attractors in your work are growing to be much more complex and comprehensive, with cultural references in a more trend-conscious fashion.

TSQ What’s fascinating about the attractor is the idea that there is a deeper reality to everything. The way things are structured, the geometry of reality, is a result of this deeper layer of topology. A good example DeLanda gives is that soap bubbles are round, and salt crystals are cubic, but both of them actually share the same attractor, because they’re both energy minimization processes—finding the minimum amount of energy possible to hold its shape. So it’s the same attractor that creates a sphere or a cube. But just because something is an attractor doesn’t mean that it possesses some eternal or universal quality. It’s just a random feedback loop.

LEAP To the average viewer, the link between the visual identity of TBP as a fashion brand and the rocks is quite peculiar. Beyond the fact that you treat these elements in a non-differential way—as simply materials—why choose these two highly disparate motifs?

TSQ This exhibition has a pretty nerdy title, “Biogenic Mineral.” It’s an attempt to interpret culture as a geological process, in its generation of materials. What I’m trying to get at here is the diversity of reality. Rocks and strange constructs like brands belong to the same universe, and they’re created by the same mechanisms. In philosophy, Levi Bryant often uses this term “flat ontology,” which means that everything ultimately is the same, or just variations of the same thing; there’s no hierarchy to ontology, everything just exists and should be treated equally, as opposed to a phenomenological perspective that privileges consciousness. Pairing these seemingly disparate forms is to prove this point.

LEAP In the outdoor shoots for TBP, elements of architectural constructs are also evident. Were you consciously trying to include these forms as well?

TSQ Definitely. These housing projects in China are really unique. You don’t find them anywhere else. I’ve been thinking about China as this giant processor of materials and the effect it has on the planet. Here I’m trying to emphasize this geological process.

LEAP By making this analogy between culture and geology, you’re inciting a refreshing view of our material culture, where the self-organizing behaviors of matter are made apparent.

TSQ Culture is the self-organizing matter. The link I’m trying to draw is that us arranging matter for a funeral or a garden isn’t so different from arranging matter for a commercial site, like an Abercrombie & Fitch store for instance. The mechanisms and processes that are involved are the same.