YUKO MOHRI: THE ORDERING OF DYNAMICS

| May 25, 2015 | Post In LEAP 32

PHOTO: Yohta Kataoka

Yuko Mohri is an installation artist. Her installations are strange. Under her spell, the exhibition space becomes a self-operating, animatronic stomping ground: chirps, bursts, flashes, and dashes of mechanical life invade the galleries like scenes from Fantasia, the 1940 Walt Disney animated classic. Umbrellas spin, balloons swell, feather dusters skitter across the floor. Pianos play themselves, drums too, and rolls of paper unfurl themselves into tubs of water. To all appearances, these objects move of their own accord, at once resolute and nonchalant. The artist’s role seems to be that of an intermediary, as if she persuades these objects to behave as they would were they alone. In actuality, the objects act as intermediaries, persuading physical forces to reveal a natural order we are simply not accustomed to seeing.

PHOTO: Yohta Kataoka

In the context of the everyday, objects are obedient: the umbrella opens when it rains, closes when it does not; the piano sounds when we desire music, remains silent when we do not. When these same things are modified—with electrical wires, small motors, sensors—and presented anew by Mohri, the certitude with which we previously regarded them is suddenly disrupted. A tiny uncanny valley opens. Yet we need not suspend our disbelief; the disruption is maintained within the oasis of the scientific real. It is also unburdened by decorative function, a blessing that distinguishes Mohri’s use of the readymade from that of many other artists. (Of course, Mohri’s training and experience do not permit her installations to be displeasing to the eye; each is a classically composed landscape unto itself, a unified and arresting entity.) She states, “I could draw, or I could paint. But I prefer gravity, magnetism, light, and wind to control my work.”

In the art world, one might see Mohri as a twenty-first-century iteration of Atsuko Tanaka. The Gutai associate, who passed away just before Mohri completed her MFA at the Tokyo University of the Arts, was known for bringing everyday objects to the exhibition and, by applying a bit of electricity, coaxing out immateriality. (This process was most evident in Tanaka’s early Work (Bell) (1955), where a series of electronic bells sound around the space.) Yet while Tanaka’s works seek to remind viewers of the existence of objects, Mohri’s show us the more fundamental components that make them up. The quality of the immaterial, in Mohri’s installation, is invisible material.

As Mohri tells it, she began conceding sovereignty to the laws of nature after attending a sound art performance while still in school. She was struck by an impulse to transform “the invisible into sound and energy.” Her MFA graduation piece did precisely that, albeit obliquely. Titled Taiwa-Hensokuki (literally, “dialogue-transmission”; 2006), the wall-mounted installation links two computers in one loop. The first computer runs speech synthesis software into the speech recognition software of the second, which in turn sends the recognized text back to be synthesized anew. At the same time, a printer spills accumulating errors onto the floor below: an increasingly nonsensical instantiation of entropy. A digitally skewed second law of thermodynamics.

PHOTO: Yuko Mohri

The push and pull of natural forces in Yuko Mohri’s work symbolize the varying effects that all things exert on one another, even when this relation is veiled by software code. Or, as in the photography project Moray Moray Tokyo (2014), by DIY hardware. Beginning in 2009, Mohri started to document the makeshift devices concocted by Tokyo subway maintenance workers to combat water leaks in the city’s underground stations. Here, plastic sheeting, bottles, bags, masking tape reveal precisely how nature directs human action (the leaks are primarily caused by Japan’s incessant earthquakes, both major and minor, and heavy precipitation). Equally important for Mohri, however, is how they reveal the “root of artistic ideas.” While photography- and project-based work are unusual within the context of her overall practice, in Moray Moray Tokyo they allow her to extend her core concerns outside of the exhibition space—fittingly, for on our daily commute we never would have noticed these amateur installations without her assistance.

PHOTO: Yuko Mohri

Most obviously and frequently, causation is not veiled at all, but concretized by object-based installations. The exhibition space becomes a makeshift biosphere in which Mohri invigorates the inanimate with gravity, magnetism, and electricity. It is appropriate to compare these installations to traditional Japanese gardens: artificial arrangements of natural objects that symbolize nature as a whole. One might argue that this comparison is fallacious, given that Mohri’s arrangements are not of natural objects, but of artificial objects. But to make this counterargument is to remain on the very superficial dichotomy that Mohri strives for us to see through.

We tend to divide nature and artifice clearly. If an object emerges into being without human intervention, it is “natural.” If we take part in an object’s creation, it is “artificial.” By this logic, the home of a bee is part of nature, and the home of your neighbor is not. To Mohri this logic is eternally faulty. Recently, the world of objects has drawn her to the pinnacle of human intervention: the landfill. In these massive, stinking depositories of refusal, she sees purity. Mining, processing, manufacturing, and consumption … process after process after process, the accumulation of artifice concluding in the archetype of nature: landscape. Waste is revealed as utterly organic, atomically reflecting the whole of reality. Garbage is narrative.

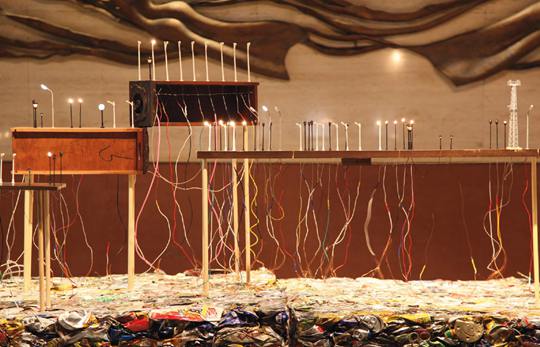

PHOTO: Yuko Mohri

Of course, to say trash tells a story would be anthropomorphic, and anthropocentrism goes against the formal logic of Mohri’s practice. Urban Mining reveals the artist’s growing interest in cities as accidental systems, not as pinnacles of human accomplishment. Its title refers both to the recycling and manufacture of waste and to data collection analysis. For the installation, which has had wildly differing iterations—for Transmediale at the Haus der Kunst der Welt in Berlin, at 1335Mabini in Manila, and as an accompaniment to a set design for The Rite of Spring—Mohri dangles electrified aluminum cans from tiny model street lamps that illuminate only irregularly, because the wires cannot complete the circuit unless pushed by air currents. No system is without coincidence, or fragility. In these microcosmic urban systems, and indeed in all of the artist’s orchestrations, the only absolute is the uncertainty of human control.

Over the years, Mohri’s obsession with the potential hidden between objects has come to serve more than just her audience, feeding back into her own understanding of self and universe. Magnetic Organ (2004-2011) is a highly complex contraption of which Rube Goldberg would be proud. In its 2004 showing, it relied on one simple magnet to stimulate a motor that, through various devices, ultimately generated sounds—aural reminders of the forces behind the contraption. Its second iteration was Mohri’s first and only attempted response to the aftermath of the Great Japan Earthquake. Amplifying no more than the invisible resources of the exhibition space—sunlight, wind, and the footsteps of visitors—the work’s commitment to revealing orders of power extends beyond the mechanical and into the political. What it reveals to Mohri, however, is her own powerlessness in the face of the political, or of historical reality. As a buffer against the unreality of representation, her practice has burrowed deeper into the residual traces behind objects, the lens of the rational ultimately focusing in on the irrational.

PHOTO: Kuniya Oyamada

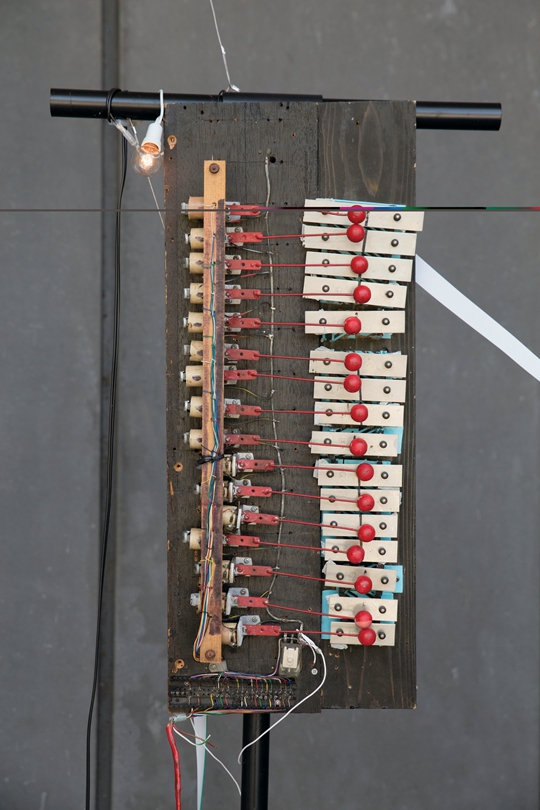

A year or so after the Tohoku disaster, perhaps because with that event the natural order of things had been so blatantly exposed, Mohri’s systems began to be drawn to matters of the spirit. The accordion-and-seesaw ensemble of Fort-Da (2012) is based on the Freudian death drive and the boundary between life and death. I/O—Chamber of a Musical Composer (2014), shown at last year’s Yokohama Triennial, is essentially a requiem for Victor Clark Searle, a little-known American musician who immigrated to Tokyo in the 1950s and later died there alone. Mohri only met him once; the idea behind the contraption was to resurrect or recycle a part of him through the instruments he left behind, which would have otherwise ended up in a landfill. Before this came Oni-bi (Fen Fire) (2013-14), which draws on fiery manifestations of souls in Japanese folklore; conductive strings spark eerily in the light of dusk at the whim of the wind, controlling a glockenspiel designed by the late composer.

In both works, a familiar trope is obvious: sound acts as a literal voice for invisible forces. Yet the forces suggested are not those of classical mechanics. Where Taiwa-Hensokuki revolved around the second law of thermodynamics, the spiritual explorations of Mohri’s post-3/11 creations are in the orbit of the uncertainty principle. Gravity and electricity are now presupposed to be mystical, controlled by the otherworldly. While building on rich prescientific traditions of explaining the natural world by way of the supernatural, this progression in Mohri’s practice shares moments with the history of science itself. Unexplainable phenomena have often provided the motivation for scientific inquiry. The results, however, are often equally unbelievable, requiring a certain leap of faith. Epistemological value emerges most strongly not in answers, but in the systems constructed to generate questions.

PHOTO: Kuniya Oyamada

The centrality of the system (or inquiry) to Yuko Mohri’s installation does not mean that visual aesthetics (result) is shunned. What it means, simply, is that the composition of the superficial cannot take precedence over the orchestration of the intrinsic. Her practice is intricate in transcending the surface of the individual object in spacetime, locating the dynamic trajectories that govern all objects at all points. The artist’s personal relationship with the readymade perhaps best illustrates this transcendence. Even before merging into an installation, she considers the components to already be self-operating, animatronic. She does not seek them. They seek her. By way of seemingly random intersections—with Victor Clark Searle, or a Nigerian recycler she met in Berlin from whom she acquired a broken computer—they append themselves to Mohri’s person. After arriving at her workspace, they wait to be summoned to their next destination.

This sounds like chaos. But chaos, Yuko Mohri reminds us, is a property of all systems.

TEXT: Einar Engström

TRANSLATION: Xu Danyu