SOCKETS

| July 28, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

Courtesy the artist and dépendance, Brussels

In 1915, the American Modernist magazine 291 published a collection of Francis Picabia’s portraits mécaniques, tongue-in-cheek drawings imagining the proto-Dadaist’s fellow artists as machinery. At the center of the spread was Portrait d’une Jeune Fille Américaine dans l’État de Nudité (“Portrait of a Young American Girl in a State of Nudity”), an exactingly rendered image of a spark plug branded with the promise, “FOR-EVER.” The portrayal of an American woman as a tireless arousal machine was more than a sophomoric sexual slight; it was a boast on the part of the artist, advertising his embrace of the potentially alienating innovations invading and reshaping his world.

Courtesy the artist and dépendance, Brussels

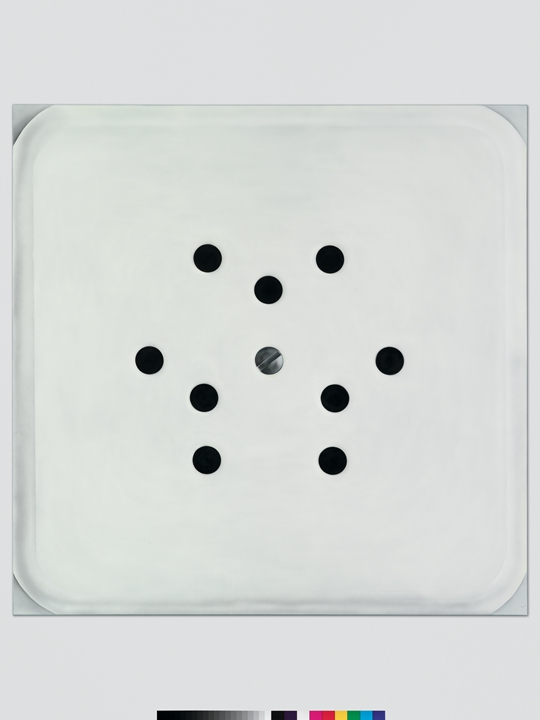

To begin a discussion of Jana Euler’s Where Energy Comes From, a 2014 trio of “portraits” of electrical outlets, with Picabia—rather than, say, Precisionist Charles Sheeler or New Objectivist Carl Grossberg—is to emphasize the caustic wit in Euler’s work. Her willingness to dip and swerve into whimsy and symbolism helps the painter evade any one prevailing aesthetic alliance. In the monumental two-and-a-half-meter Beer without Glass (2014), it is the mug that is left invisible, its contours mapped out by foam-capped amber liquid that stays true to the shape of the unseen vessel. This play of the visible and the concealed figures more directly into other series, where Euler gives her figures multiple eyes or, conversely, no eyes at all.

Courtesy the artist and dépendance, Brussels

In the three paintings of Where Energy Comes From, the “eyes” are the dark sockets, which peer out, unblinking, into space—emoticons of indifference that stretch across two meters each, tweaking the sense of scale as if the walls have shrunk or their attributes expanded. If the Picabia portrait riffs on fresh technology, Euler’s outlets look pointedly anachronistic. Anchored with mismatched screws, the outlets are cheaply made, in the dingy eggshell palette of industrialized decor. Sexual punning is inevitable given that even the technical terminology for the receptacles is gendered, with the “female” holes eager to receive the “male” prongs. In this sense, the paintings call up not just Picabia, but also Gustave Courbet. After all, tucked within these dark interfaces hide the mysterious mechanisms that enable the entirety of our digital existence, powering the devices that propagate our contemporary world.