Camille Henrot: Art and Universality

| December 9, 2015 | Post In LEAP 36

Courtesy kamel mennour and Johann König

The Big Bang

After the immense success of Grosse Fatigue, which caused a sensation at the 2013 Venice Biennale and brought Camille Henrot the Silver Lion, the French artist, born in 1978, has become one of the most sought-after names for curators and institutions. The Venice exhibition, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, was fittingly titled “The Encyclopedic Palace,” for Henrot’s 13-minute video told of nothing less than the creation of the universe.

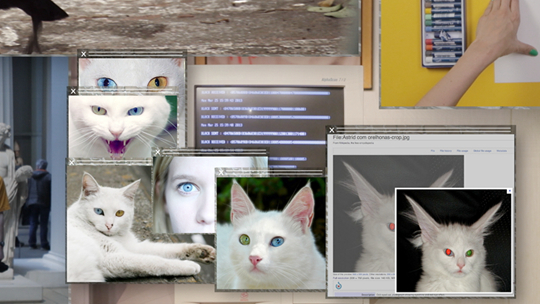

Made in cooperation with musicians and writers, the multi-layered composition works on visual, textual, musical, and vocal levels, all intertwined at the breathtaking speed of an ecstatic incantation. Henrot worked on this project it during her stay as a research fellow at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, and the massive range of image material, objects, and archival footage in the world’s largest scientific and museum complex finds its way into the monumental collage of Grosse Fatigue.

The climatic flow of images, moving to the accelerated tempo of the soundtrack, overwhelms the viewer, breathlessly trying to keep track of this information overkill. Watching the video puts you in a state of trance, riding along with the artist’s tour de-force. This condensed Gesamtkunstwerk offers an experience rather than an informative survey of the content presented. Nothing else might be intended. The vastness of the world—the natural and human histories materialized in the archives of the Smithsonian—is represented in the nut that is Grosse Fatigue, the title of which plays with a pathological term for chronic exhaustion. Our constant efforts to understand the world and ourselves, to bring order into the frightening chaos, form an ongoing topic for Henrot. This essential urge (and its vain absurdity) is reflected in her disparate and versatile constellations. As the proverbial “big bang” of her own practice, Grosse Fatigue provides the perfect entrance into her broad interests and interdisciplinary methods, connecting formal media diversity with an epistemological claim to universality.

From the History of the Universe to the Artist’s Studio

The complex installation The Pale Fox is a continuation of the encyclopedic agenda of Grosse Fagitue. Commissioned and produced by Chisenhale Gallery in cooperation with Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Westfälischer Kunstverein, and other institutions, the work toured through Europe from February 2014 through this autumn, presented most recently at König Galerie, Berlin.

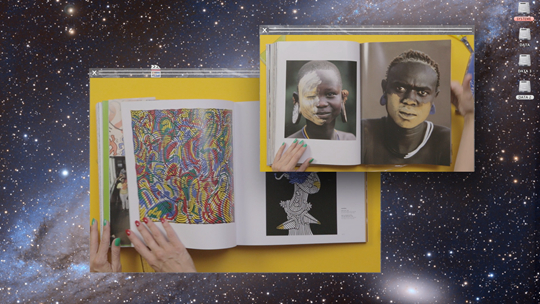

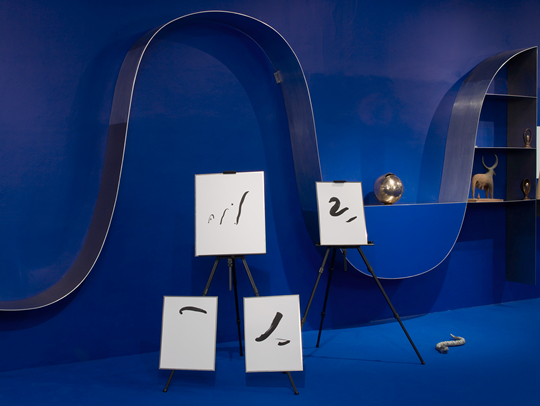

The Pale Fox again raises questions about universal systems and the diversity of the real, striving to include all aspects of human existence without the fixed binaries of culture and nature, art and life. Unlike the formally homogeneous video Grosse Fatigue, this installation is a conglomeration of architectural displays, pictures, books, photographs, sculptures, models, and everyday objects. Appearing like a huge, neutral box from the outside, the space opens through a side door that leads the visitor into a room in ultramarine blue. The soft carpet and deep blue (an iconic color open to interpretation, from the cinematic blue screen to Yves Klein), accompanied by the monotonous humming of an atmospheric soundtrack, create a meditative environment in which the visitor must find his or her way along a frieze of images and shelves filled with objects. By constantly looking and deciphering, he or she tries to make sense of it—but, instead of being shown a work, the visitor is invited on a tour of discovery, fulfilling the ideal role of Roland Barthes’s postmodern reader.

Courtesy kamel mennour and Johann König

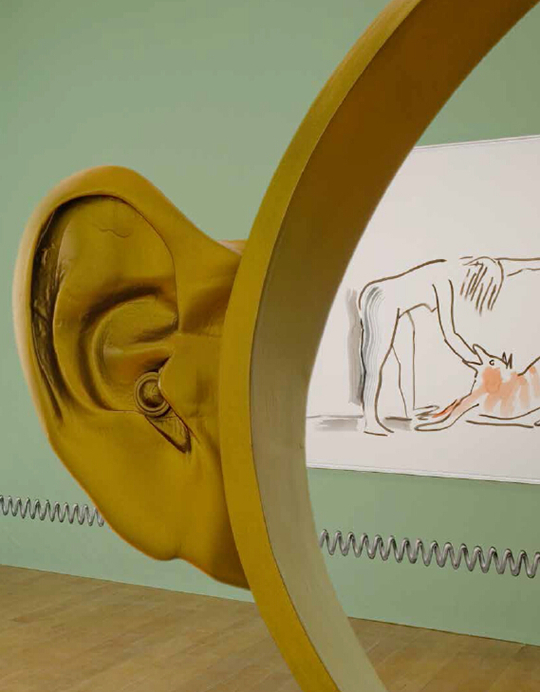

Henrot creates a primal order by attributing the room’s walls to the four points of the compass and the four elements (air, water, earth, and fire), including the human life cycle, as indicated by a baby poster. This cosmological graph, however, gives little orientation when you lose yourself in the mass of details. With more than 400 objects on display, the room presents both a macrocosmic model of the world and a microcosmic studio or laboratory, where traces of works in progress are left visible (a desk, boxes, frames, empty sheets of paper). While the room appears empty when the viewer confronts its first wall, its material mass increases until, at some point, unordered material piles up and spills onto the floor. Shelves and images on the wall present fragmentary orders based on formal similarity (the shape of a snake) or background relations (the magazine of Jehovah’s Witnesses in several languages). Digital media and junk, pop and science, high culture and low mingle everywhere: is the Big Bang an astronomical term, a Korean boy band, or a television show?

Courtesy kamel mennour and Johann König

Henrot’s obsessive compilation offers an experimental framework for associations, open to countless layers of meaning across the fields of cultural history, science, philosophy and religion. As in Grosse Fatigue, here this information mass echoes the human obsession with explaining, ordering, and documenting reality in order to control it. Ingestion and production are so closely linked that there is hardly any difference between taking in the world and shaping it by constructing explanatory models. For Henrot, chaos looms above all as the antithetical but necessary force in this anthropological dialectic: it feeds creative dynamics while at the same time subverting any comprehensive order.

The pale fox Ogo is a god of the west African Dogon tribe, on whose mythology the French ethnologists Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen published the 1965 study Le Renard Pâle to which Henrot is referring. Her work is filled with wide-ranging references: Japanese ikebana flower arrangements (Is it possible to be a revolutionary and like flowers?, 2012), Algerian history (Collections Préhistoriques, 2013), the Houma Native American group (Cities of Ys, 2013). They all attest to her quasi-scientific, associative way of dealing with historical and ethnological topics by means of archiving and arranging.

Courtesy kamel mennour and Johann König

The Problem of Universality

But how can an art practice with such an all-encompassing appetite for non-artistic systems of knowledge find an adequate way to handle all this material? Is it possible to articulate problems of science, history, economic and cultural productivity, and the vast complexity of the world plus the individual life in one work? How far is scientific research compatible with artistic practice? These questions are crucial with research-based art in vogue and references to science and history have become a common claim among artists. When specific media and classic genres no longer set boundaries or provide content, the spectrum of possibilities becomes endless. Where everything seems possible, the tendency towards universality is an extreme way of embracing the situation.

This is neither a return to the Renaissance ideal of the Uomo Universale nor a turn to the notion of art as a universal discipline connected to natural science and philosophy, but rather a symptomatic consequence of our overfed information culture, with its endless cacophony of media, sources, narratives, and opinions. Fields of knowledge intertwine and material becomes increasingly easy to access. Trends towards interdisciplinary, open-source culture encourage diversity in art, but being open to all sides risks becoming superficial or illustrative. Too often, art borrows meaning from arbitrary references, merely touching on topics with citations or translations, instead of finding an artistic formulation that speaks for itself.

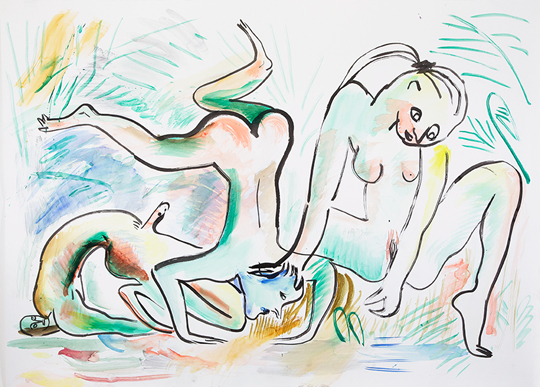

Courtesy the artist and YARAT

Despite her sprawling referential framework, Henrot tries to find a suitable artistic form in analogy to the other disciplines she addresses. It works out better in the dynamic digital staccato of Grosse Fatigue, while the analogue form of The Pale Fox discloses, in its static arrangement, the basic problem of her method: relations can verge on referential randomness (anything can mean anything) and elements become fleeting citations (anything can trigger associations). The richness of Henrot’s work derives from her non-hierarchical attitude towards our present and past. Her latest drawings, inspired by Nicki Minaj’s controversial music video for “Anaconda,” prove this point, regardless of their awkward primitive style.

There is a naïve enthusiasm in her extremely inclusive, heterogeneous art practice. The results are certainly fascinating, yet often leave viewers at a loss, as if the mass of information presented had promised some understanding it could not fulfill—but this undecipherable approach everything seems to be exactly the point. Universal confusion is not the problem, but the program. In the end, it is an interesting tackle of the absurd wish for universal comprehension, which has been approached with more self-reflective irony by everyone from Fischli/Weiss to Bouvard and Pécuchet, who tried everything and failed ingeniously.