DISTRIBUTING THE SENSIBLE

| December 24, 2015 | Post In LEAP 35

The moment we arrive at a threshold, we often already know what to expect. The senses distill for us where we are and what we’re supposed to do: as when entering a coffee shop. Increasingly ubiquitous, these houses of high culture appeal through a blending of aromas and symbols; we feel comfortable, worldly, and know how to act. Coffee, in many parts of the world, is both a necessity and an indulgence at once. It offers routine, repose, a feeling of timelessness—and free Wi-Fi. Coffee is also marked by its origins. From “the rugged Sierra Madres of Oaxaca, Mexico” to “a gently roasted blend from Latin America and East Africa,” exotic descriptors indicate that flavor is cultivated and authenticated through the recalling of place.

A brew may contain “floral, peppery spice notes,” or “lemony accents,” but this flavor will only be known to those who are able to access it and are educated in its nuances. The French philosopher Jacques Rancière suggests that our senses are colonized by what is made perceptible and to whom, and that it is through these delicate registers of taste and aesthetics that order is imposed and maintained. Hence the far-reaching distribution of coffee beans around the world—which dates back to the fifteenth century, preceding many fraught colonial exchanges—can be said to instigate both inclusion and exclusion. For example, today a new coffee shop on the block marks a new phase for an old neighborhood: lattes and incandescent lighting usher in a very specific crowd while indicating to others that they are not wanted.

A similar connoisseurship attends the tradition of film. Hollywood has served as a homogenizing force whereby narrative and affect are determined by corporate and box office interests. Audiences arrive with expectations on what they will feel and what kind of action they will experience. Directors in turn have the responsibility to fulfill these. It is in opposition to this logic that Tsai Ming-liang, of the Taiwanese second generation New Wave, has recently moved into the territory of art. No longer showing his films in theaters, instead his works traverse the museum and gallery circuit, viewed in specially curated settings. At the Times Museum in Guangzhou this past July, Tsai’s 2014 film Stray Dogs was shown in rooms transformed by soft crumpled paper and stacks of foam—in effect a post-apocalyptic utopian womb where reality seemed something to slip in and out of. The all-encompassing environment allowed space for contemplation while limited distribution ensured that each viewing was distinct.

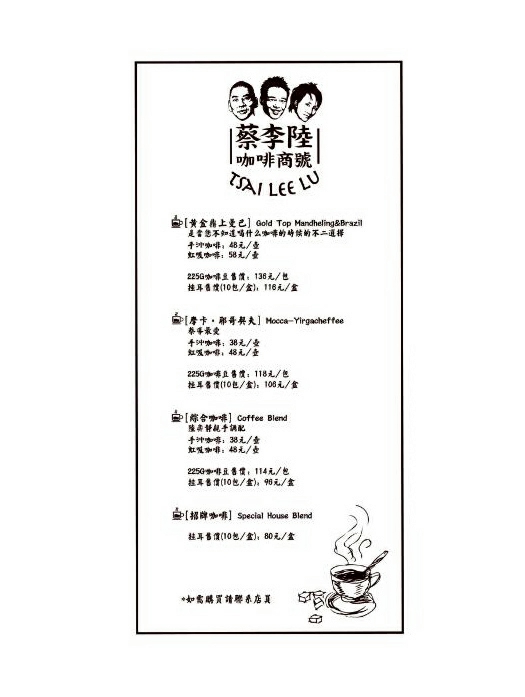

Meanwhile, in the museum cafe coffee was served. Tsai, along with his lead actor and actress, has expanded his trade to include his own beverage brand, Tsai Lee Lu, and the cafe walls featured an array of photographs of the three happily accompanying their product from bean to brew. Coffee is at once common and highbrow. It can be filtered (as in any American diner) or syphoned (a high tech technique imported from Japan). When the director David Lynch refers to coffee in his TV series Twin Peaks (“There was a fish in the percolator!”), it contributes to his American Gothic appeal, which contains a reverence for the banal. Lynch’s own coffee brand strives to be as un-pretentious.

Perhaps there’s something to be said for cult figures who dabble in producing their own commodity. It is where fantasy can be momentarily attained, and for a modest price. When we sip a freshly brewed Tsai Lee Lu roast, the senses expect the surreal—as a woman in a red sequined dress dancing seductively with a fire hydrant, or a man growing scales while soaking in the steamy excesses of a water tower—but instead the taste is strangely soothing. In fact it may reveal that it is in extracting something from its usual context that we can experience the pure joy of the expected.