PALPABLE AND PRESENT: ANICKA YI

| December 22, 2015 | Post In LEAP 34

In 2013, Korean-born, New York-based artist Anicka Yi began a trilogy of exhibitions entitled “Denial,” “Divorce,” and “Death,” inspired by human emotions attached to love and heartbreak.

Presented as a forensic investigation of these affective, illusive, and hardly measurable states, Yi’s work captures the signs, evidence, and residue of these phases embedded in and transmitted through text messages, spaces, food and fluids.

“Denial,” at Lars Friedrich, Berlin, focused on states of denial: denial of truth and denial of desire. The press release included an exploration into how these phases reveal themselves within law, economy, and science. Works in the exhibition were placed within lit carved-out spaces in the walls. “Divorce,” at 47 Canal, New York, incorporated an arrangement of cardboard boxes, objects that signify moving—moving out, moving on—but themselves remain indifferent to the stages of life with which they are involved. Contained within the boxes were live snails. Among Yi’s material lexicon, which persists across her work, snails are self-reproducing hermaphrodites––sensually autonomous and self-sufficient producers. In the exhibition “Death,” at The Cleveland Museum of Art, the walls were painted the red of a funeral home carpet. Works were spotlit in a dim room, an environment conducive to a natural history museum or modern art. The exhibition design signified not only death but the kind of death that occurs in states of preservation. The work Sister, comprised of tempura-fried flowers stuffed into a red turtleneck, suggests through its crispy encasing a process of culinary preservation that kills the delicacy of what it intends to preserve.

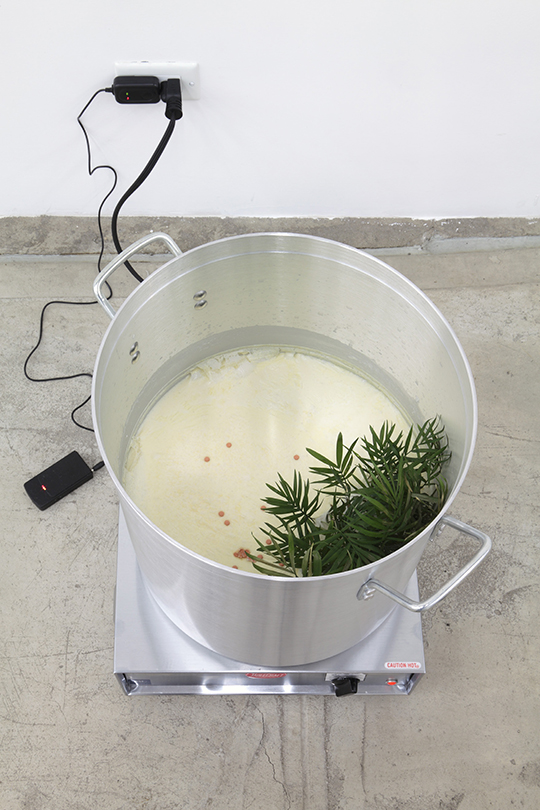

Diamond Age, which I experienced at the exhibition “The Radiants,” curated by Green Tea Gallery at Bortolami Gallery, comprises an aluminium pot on a portable electric burner. Yet, to employ the kind of experience and interpretation Yi’s work demands of its medium, describing it in visual terms is irrelevant.

To me, it smelled like when you wear your puffy winter coat all day and then enter a warm indoor area: a sweet layer of sweat accumulates on your body, and only those who get too close can smell it.

Lonely Samurai is a podcast of conversations produced by Anicka Yi as a space for dialogue around contemporary social, economic, and art world issues. In the first three episodes, she speaks to artists, collectors, perfumers, and an intellectual property lawyer, seeking the expertise of collaboration across different vantage points. Episode one, entitled “What Was Collaboration,” was a conversation with gallerist Stefania Bortolami, collector Cristina Delgado, curator Ruba Katrib, critic Andrew Russeth, and artist Amy Sillman discussing the viability of female networks and economics for women in the contemporary art world—an ongoing thread of Yi’s work. In episode two, entitled “Why I Drool,” Yi speaks to perfumer Christophe Laudamiel and artist Sean Raspet on the language of scent, particularly our limited olfactory vocabulary and ways to expand it. In episode three, “Take Your Shoes Off When You Talk To Me,” Yi converses with intellectual property lawyer and contemporary art collector Thomas Alexander.

A recent solo exhibition, “You Can Call Me F,” curated by Lumi Tan at The Kitchen, proposed the idea of feminism as a contagion. At the entrance, a shelf vitrine contained bacteria comprised of 100 swabs of vaginas, which Yi gathered from female artists and women within her social and professional circle in New York.

The bacterium was synthetically cultivated by Massachusetts Institute of Technology biologist Tal Danino. Using the aesthetics of a quarantine, the artist composed arrangements of hydro gel beads, motorcycle helmets, and dried shrimp, all with scent diffusers within spaces sectioned off by vinyl sheeting. The diffused scent was a mixture of a synthetic reconstruction of the biological material taken and the captured smell of Gagosian Gallery, analyzed and composed by artist Sean Raspet. Walking into the opening, it smelled like a lot of people: slightly sweet, dank, but also somewhat clean. The source and composition of the smell elicit analogies to fear of biological contagion, hygienic paranoia, sterilization, an ominous gathering of women, and the power and danger of virality both digital and biological.

Throughout her practice, Anicka Yi collaborates with peers and professionals to create a network of knowledge situated within a variety of experiences. Her work gains from collaborations that disassemble the antiquated idea of a singular artist as producer of ideas. In her exhibition at The Kitchen, the connections between feminism and virality—both biological and social network—identify ideas that are built upon, collectively felt, sensed, and travel via mass media. Yi’s work is personal, and requires a personal interpretation of material operating within life phases such as denial, divorce, and death as a consequence of activating other sensory triggers in memory.

The solo exhibition “6,070,430K of Digital Spit,” at MIT List Visual Arts Center, culminated her research and collaborations at the university, where Yi was a visiting artist, by ruminating on the politics of taste—as both a sense and as aesthetic discernment—communicated through olfactory, gustatory, and auditory flavors. Featuring a large, illuminated pond containing synthetic and biological matter and the cellulose “leather” that grows from the bacterial cultures in kombucha tea. To me, the material of the cellulose leather signifies both the cultural taste of a hippie-hipster who grows kombucha and the scientific turn toward engineering natural substances, such as lab meat. The installation also featured an intermittent soundtrack playing over speakers, playing on ideas of good and bad taste throughout. Another solo exhibition, “7,070,430K of Digital Spit,” which opened at Kunsthalle Basel in June, features new work referring to and taking up themes from “Denial,” “Divorce,” and “Death,” mixing elements from previous works to conclude with the theme of forgetting. The exhibition engages in the very process of forgetting—a loss or modification of encoded information in long-term memory—and serves as a finale and ode to the past five years of work. Again, we see materials like dried flowers (from the exhibition “Death”), snail excretions (from “Divorce”), and bacteria (from “You Can Call Me F”), all preserved and contained in plastic orbs and glowing vitrines set into the walls, both situated in dimly lit rooms. The exhibition is accompanied by an art book printed on incense paper imbued with an original fragrance devised by Yi in collaboration with the perfumer Barnabé Fillion to embody the smell of forgetting—meant to be burned after reading.

Anicka Yi’s exhibitions treat the white cube of the gallery as an isolated viewing space, a testing ground or laboratory similarly imbued with its own false representation of neutrality. Within her trilogy of exhibitions “Denial,” “Divorce,” and “Death,” we sense the desire to present proof of subjective collective experiences and simultaneously challenge notions of an ocular objectivity both socially and scientifically. In A Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway suggests that vision is the primary means of verifying and truth-making: “The eyes have been used to signify a perverse capacity—honed to perfection in the history cmof science tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy—to distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power. The instruments of visualization in multinationalism, postmodernist culture have compounded these meanings of disembodiment.” Calling on a sensory vocabulary, Yi’s work is transmitted and experienced in the same ways that the topics she takes on are felt and experienced: known yet elusive. Her works emphasize presence and being, and the collapse of the distance between what is known and who knows it. Her viewers must digest sensory information; they are forced out of the objectivity of viewing and acknowledge their bodily participation. Consequentially, Yi’s work is smelly, and her sculpture—resilient yet precarious skins—is far from solid. They evaporate, crumble, melt, collapse, and die.