A GREAT DISTURBANCE IN THE FORCE: ART AND MASS MEDIA IN THE 1990S

| January 21, 2016 | Post In LEAP 36

Scholar Dai Jinhua, in his discussion of the ideological constructs of mass culture in the 1990s, says that, at that time,“farewell to revolution” became the profound and tragic social consensus. This turn occurred alongside the end of the Cold War and Fukuyama’s “end of history,” originating in the disruptive influence of market reform on intellectual culture. In 1992, after Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour, the force of commercialization that had begun in the 1980s swept over society like a tidal wave. Marketization was an economic phenomenon, but it was also a profound event for social, political, and cultural systems, bringing all of them into the market’s trajectory. The aphasia of the intellectual world and the rise of mass media, Mr. Socialism and Mr. Capitalism, China and the west, tradition and modernity. The system of values achieved across the twentieth century, through revolution and subsequent reform, faced a huge crisis. Even today, global market forces are the most powerful hands writing China’s history; China has yet to walk out from the crisis of market logic and historical perspective that began in the 1990s. For philosopher Wang Hui, the important thing about the 1990s is not their shocking beginning, but rather the fact that they have never “departed.”

Market economic reforms in the 1990s took the power structures of China’s past and transformed them into structures of corporate and individual capital. This transformation was especially evident in the rapidly expanding media industry. In 1993, central and local television stations came out with seasonal contracts for the first time. Official newspapers were revised one after the other, adding leisure weekend editions and supplements; foreign luxury and fashion publications made their debut; and a dazzling array of consumer tabloids covered newsstands. Hand in hand with the rise of mass media was the rise of the lucrative advertising industry; intellectuals in the humanities ended up going into business as talking heads and copywriters.

Faced with all this new cultural industry noise, intellectuals with broader concerns suddenly lost their voices. They experienced the failure of discourse in the 1980s and found no way to define, with their existing knowledge frameworks, the bizarreness of the 1990s. In the 1980s, intellectual discourse centered on utopian ideals like progress, development, and modernization. It omitted the social realities of the market, capital, and desire. In the face of the political pressures of 1989 and the commercial frenzies of 1992, abstract concepts of subjecthood, human freedom, and emancipation seemed pale and feeble by comparison. Out of instinctive resistance to the rise of the market, intellectuals of the early 1990s stimulated a wide variety of cultural breakthroughs. In 1991, there was Scholars, a new academic journal that reflected the 1980s craze for western theory and called for the return of intellectuals to “Chinese cultural identity” and “homegrown cultural resources.” At the same time, some scholars continued toward postmodern theory in search of a way to rescue the nation. Ultimately, the linear historical narrative of postmodernism did not so much have its finger on the pulse of contemporary culture as it did deepen the preexisting anxieties of the intelligentsia: was China of the 1990s China a logical progression, or a deep fracture? Should one fight for humanism or surrender to mass culture? A consensus of the loss of the humanist spirit indubitably implied the general defeat of the socially influential Chinese intellectual.

Unlike in the 1980s, the theoretical output of the intelligentsia in the 1990s did not resonate with artists. Instead, the mass media’s rapid output, widespread circulation, and unparalleled immediacy and visibility challenged artists’ ways of thinking and working. Mass media, having obtained a new discursive power through market reform, was, in a sense, quickly replacing critical discourse as the most important force influencing artists.

The relationship between mass culture and art is often reduced to those paintings filled with misappropriated popular symbols of the 1990s and willingly absorbed by the market. It is worth emphasizing that, in the early part of the decade, several artists began to consider mass media from a critical standpoint, transforming it into a vector for art. In 1988, after graduating from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Wang Youshen became the first art editor for Beijing Youth Daily (BYD). As the official newspaper of the Communist Youth League committee in Beijing, BYD was a traditional media outlet and a classic symbol of power. At the start of the 1990s, the newspaper’s operations began to turn towards the independent market. Wang spearheaded the paper’s visual transition, designing a new layout with a system of visual markers and adding striking pictures to increase readability. The graphic aesthetic of BYD became an important part of its brand, and, in 1994, circulation reached 400,000 copies. This sharp rise in the power of the paper’s public image came in part from the cultural capital it accrued in marketization. During the same time, Wang Youshen’s own work benefited from a deeper knowledge of the production, distribution, and consumption of newspaper images. This understanding would become the basis for his practice.

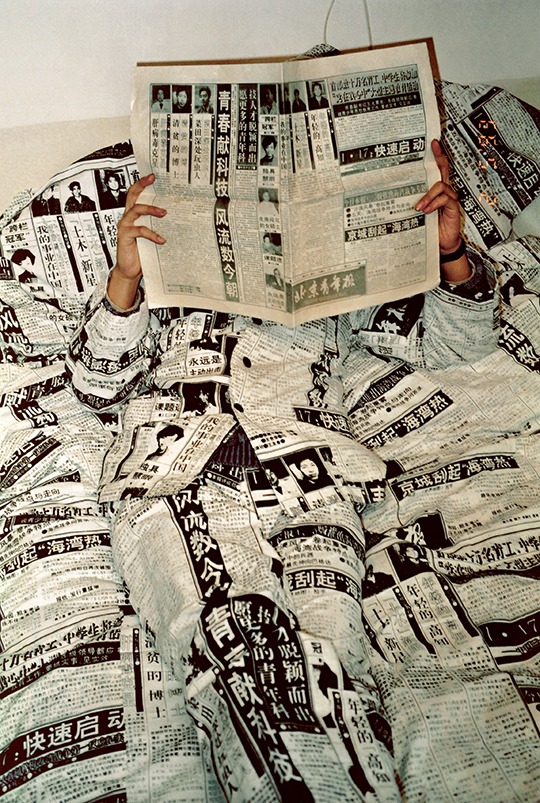

In 1991, for the “New Generation Art” exhibition at the National Museum of China, Wang silkscreened an issue of BYD on white cloth and turned it into curtains hanging over a large glass museum window. Sunlight pierced through the print and shrouded the dignified hall in newspaper graphics. In a performance piece titled Newspaper: Reading the Newspaper, the artist ventures into the street dressed in a tunic made of a similar fabric and buys an issue of his own design. He then goes home to read it, only for the viewer to discover that his linens and sofa, too, are printed with the newspaper—the very issue he just purchased. Media buzzwords, with their sensationalist urgency, are literally piled onto the artist’s body and his environment. From public sec- tor to private space, from media to epidermis: the transformative and invasive qualities of the series evoke a sense of indescribable pressure. In 1993, to celebrate the 44th anniversary of the paper, Wang designed a full-page ad in which he proposed wrapping the Badaling section of the Great Wall in newspaper. In the sky above the wall, he printed a line of eye-catching copy: “from here, into the next century.” The pairing of image and text places the landmark and the paper together under the banner of progress and innovation. But, when the piece is treated as a work In 1991, for the “New Generation Art” exhibition at the National Museum of China, Wang silkscreened an issue of BYD on white cloth and turned it into curtains hanging over a large glass museum window. Sunlight pierced through the print and shrouded the dignified hall in newspaper graphics. In a performance piece titled Newspaper: Reading the Newspaper, the artist ventures into the street dressed in a tunic made of a similar fabric and buys an issue of his own design. He then goes home to read it, only for the viewer to discover that his linens and sofa, too, are printed with the newspaper— the very issue he just purchased. Media buzzwords, with their sensationalist urgency, are literally piled onto the artist’s body and his environment. From public sector to private space, from media to epidermis: the transformative and invasive qualities of the series evoke a sense of indescribable pressure. In 1993, to celebrate the 44th anniversary of the paper, Wang designed a fullpage ad in which he proposed wrapping the Badaling section of the Great Wall in newspaper. In the sky above the wall, he printed a line of eye-catching copy: “from here, into the next century.” The pairing of image and text places the landmark and the paper together under the banner of progress and innovation. But, when the piece is treated as a work of art rather than an ad, Wang removes the line of copy. The Great Wall wrapped in newspaper, the curtains at the Chinese National Museum: these relationships possess a similar dialectical dynamic between internal and external, closed and open, transparent communication and defensiveness, government and market, monitoring and free exchange. As Pi Li writes, “The way he positioned the newspaper in these critical spaces shows that Wang Youshen had begun to develop a conceptual understanding of the media.”

Wang was the first artist to use the newspaper for the transmission of contemporary art. In 1994, when he was art director for the paper, Wang curated the “1994 Interior Design Art Proposals Exhibition.” The exhibition on paper was organized with a commercial title sponsor, and invited 12 artists—among them Gu Dexin, Wang Jianwei, and Wang Guangyi—to publish proposals in the paper. Li Yongbin’s proposal, the featured work for January, was an open, single-occupant dorm room with one blade of grass growing out of a concrete floor. These highly personal pieces of “apartment art” embedded amid the newspaper’s art news, market summaries, and advertisements created a sort of mosaic, an implicit sense of some kind of rupture in the textual environment.

The practice of appropriating mass media also included projects in which artists put out their own small newspapers. One day in July, 1999, artists Zhang Dali, Zhu Fadong, Wang Jin, and Wu Xiaojun went into the crowds at the International Exhibition Center in Beijing and scattered copies of a small journal they had published. These three artists, having found themselves outside the system, did not wish to remain on the margins of society to create underground exhibitions that would only be seen by other artists. Drawing inspiration from the leaflets and street advertisements of the time, they promoted their ideas like urban guerrillas. Though the original intention was self-promotion, they also hoped to interfere with reading habits. Their tabloid adopted the popular broadsheet, black-and-white layout in four sections, but their typeface gave the illusion that it was an insert from a larger newspaper.

Zhu Fadong planted his own image where the centerfold advertisement should go, and turned the passport in his “Identity Card” series into a full-page advertisement. More than half of Zhang Dali’s section is comprised of an essay in English introducing his graffiti practice, with a photograph of his iconic human head tag inserted midway through; the bottom right corner was devoted to an interview on the question of whether or not graffiti is art. Below this, the words “low prices” and “the big winner,” with a fat arrow pointing right up at him, subtly link art and commodity, medium and advertisement. Wang Jin’s page is divided into upper and lower sections; the top is a photograph, and the bottom is the same image with migrant workers cut out. In their places, he inserted popular media buzzwords: “explosion,” “democracy,” “development,” “efficiency,” “reform,” “art,” all densely packed together so the reader loses his sense of direction. At the bottom, an annotation reads “names in no particular order,” conveying the sense of a competing urgency among them.

This project, “Talents,” smacks of art’s utopian proclivity to push in the direction of the masses. More importantly, the intertextuality of the newspaper so liberally endows the texts with possible interpretations. After 2000, with the ubiquity of real estate developments, several artists continued similar practices of appropriation and intervention with real estate advertising printouts and flyers.

Mass culture in the 1990s drew criticism from cultural scholars for its buried ideologies, but the complexity of marketization meant that, while it produced problems, it also provided new opportunities. Yes, we bid farewell to a century of revolution, to intellectual enlightenment, and to an imagination of rationality—but now artists had the opportunity to shift to market mechanisms in pursuit of inspirations and outlets. Through interventions in media, they were able to improve their visibility in society and increase their participation in public affairs. The imagery and modes of presentation these artists created brought with them an unprecedented sensibility of the contemporary. Moving towards the market was not, in fact, an entirely tragic historical fate, because mass culture’s “City of Mirrors,” to quote Dai Jinhua again, was never an entirely impenetrable fortress. New possibilities are hidden in the cracks between those mirrors, and artists are precisely those to go in search of them. (Translated by Katy Pinke)