Where are they now? Tracking the neo-geometric conceptualists

| March 31, 2016 | Post In LEAP 37

Acrylic, bronzing powders, laquer, silk-screen on plywood, with chrome plated brass, anodized aluminim plus anylux, 86.4 x 43.2 x 38.1 cm

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

We live in a state of the perpetual present. With the revolving door of exhibitions in more and more venues, commercial and scholarly alike, thousands of artists appear on a relatively flat plane of aesthetics. This is good for a lot of things—fair art criticism among them—but it tends to hurt our understanding, as viewers, of where the art is actually coming from. Neo-geometric conceptualism is a case in point. Best known as Neo-Geo (and also called Neo-Conceptualism and Simulationism), the 1980s East Village movement involved a redeployment of minimal strategies from conceptual art in relation to popular culture, melding aspects of pop art and conceptualism. Many of its leading artists are now well-known on their own. LEAP takes a look at how their work has evolved, and what they might still share.

Lacquer and acrylic on polymer resin and plywood with anodised aluminum, 172.7 x 121.9 x 38.1 cm

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

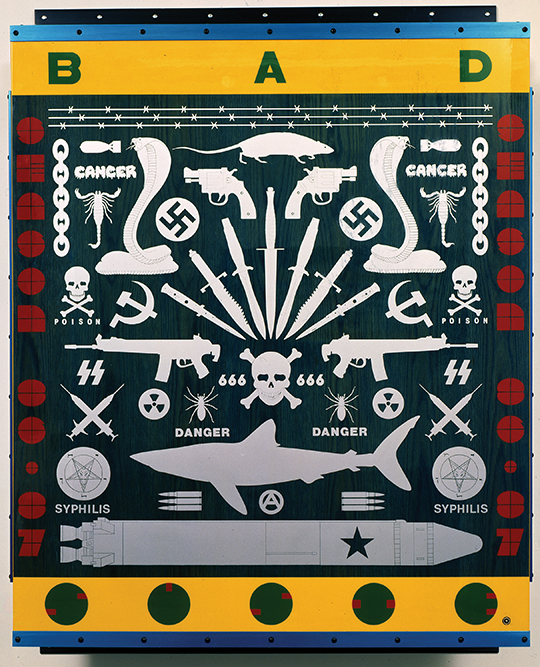

Ashley Bickerton

When Bickerton lived in New York, he made formally pleasing, strictly geometric structures in two dimensions and three. His “self-portraits” gathered corporate and brand logos on minimal plates, while other work played with product packaging in intricate superimpositions of boxes, cables, and bars. He left in 1993, and now lives in Bali. His recent work takes on the cultural politics of his adopted home in the form of figurative paintings of the future-indigenous and assemblages of maritime pollution. While the images at the core of his subject matter have undergone a massive shift, the framing devices remain constant across Bickerton’s great migration.

Paintings and digital prints

ArtBo art fair, Bogota, Columbia

Peter Halley

Halley’s work has remained remarkably consistent. His 1980s paintings developed his practice through the simplest elements: squares (“cells”) and lines (“conduits”) on solid color fields that told short, witty stories. It was these paintings that delivered the theoretical and visual basis for Neo-Geo as a movement, so it makes sense that the original images continue to be relevant even today. Halley’s paintings have become a bit brighter, a bit more textured, and a bit more varied in composition, but the bones remain. (The titles have also become a lot funnier.) Today they recall more robots and screens than circuits.

Jeff Koons

Koons is the golden boy of Neo-Geo, and his market success has functioned as the rising tide keeping interest up in his East Village compatriots. His interests in pornography and branding are shared with Bickerton, and his deployment of the readymade is echoed in Steinbach; aside from these attributes, however, Koons is the least recognizably abstract or geometric (unless one counts, of course, the golden ratio of the basketball in a fish tank, produced at the heyday of the movement). Koons’s work has become much glossier and production-dependent, but the core project—creating formal devices with which to frame commercial readymades—stands.

Bronze, 13.3 x 48.9 x 21.6 cm

Edition 1 of 12

Courtesy of the Artist and Simon Lee Gallery

Sherrie Levine

As a more peripheral participant in Neo-Geo, Levine constitutes a bridge with the Pictures Generation, that other loosely affiliated group that focused more on the media rather than Neo-Geo’s more abstract mapping of society. Levine did both: in addition to her photographic practice, her work in the mid-1980s included the check paintings, which met the very definition of geometric abstraction, and the Lead Knots, in which she filled in the holes in wooden boards mounted on walls. These series find echoes today in her grids of images, but her most recent work has been taken over by her colleagues’ interest in luxury and figuration.

Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery New York

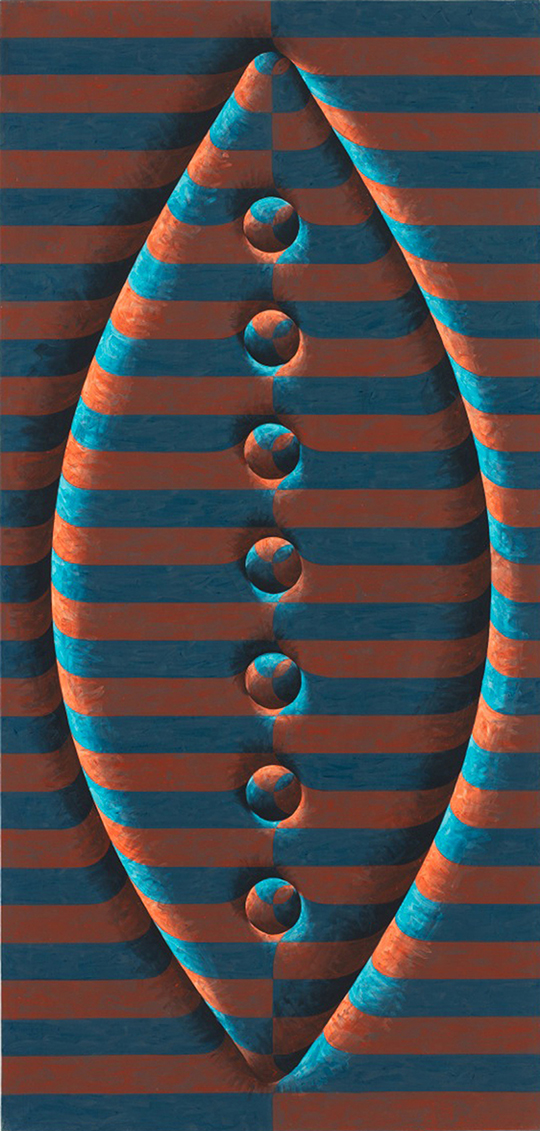

Peter Schuyff

The quintessential Neo-Geo painter, Schuyff began his work by picking up where the underrated abstract illusionists left off: his compositions gather key pictorial elements and scatter them across the picture plane, an analysis of how painting was beginning to change in the video age. His earlier work was slick, almost cartoonish—the aesthetics of auto body finish or crude oil. More recently (he continues to show almost exclusively in gallery and museum solo exhibitions), his works have allowed in much more of the hand of the artist. As the brushwork becomes evident, the illusion disappears, and his paintings become much more about painting as a practice, sometimes incorporating text in addition to more decorative motifs.

Baltic birch plywood, plastic laminate and glass box; leather and metal boots by Douglas Abraham, 123.2 x 94 x 54.6 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Haim Steinbach

Steinbach appeals to those who long for a bit more formal criticality in the toothless parody of Koons. His practice revolves on a critical philosophical insight that has taken off with the recent entry of object-oriented ontology into art theory: that multiple objects placed side by side form a new object with new possibilities and meanings. Most brilliantly, his work automatically updates with the cultural context. His 1980s work juxtaposed household objects with figures from then-current films; a more recent piece might put a toy by artist Yoshitomo Nara next to more popular toys and images from Disney films. Steinbach’s masterful shelves encompass the geometric interventions of Neo-Geo.

Meyer Vaisman

One of the less visible core members of Neo-Geo, Vaisman has enjoyed a resurgence in the last two years as he has been rediscovered through the efforts of younger artists. His best-known early work appropriated images like caricatures and repeated them in multiple iterations across geometric structures. Like Bickerton, Vaisman stepped out of the art world for some years, and currently lives in Barcelona. His most recent work, showcased in New York last year, consists of self-portraits in the form of endless repetitions of his own signature. His geometric formalism may have passed, but an interest