Zhang Guangyu: Republican Renaissance Man

| April 25, 2016 | Post In LEAP 37

Recent reappraisals of the Republican era have been a long time coming. From the inclusion of the New Woodcut movement in the Shanghai Biennale to the rediscovery of artists like Wu Dayu, academics and collectors alike have unearthed the legacies of the first half of the twentieth century. This sudden rise in interest on the part of collectors and institutions of art, both public and private, has spurred demand for further research into the evolution of Chinese modernism.

Last year’s Zhang Guangyu exhibition at the Long Museum in Shanghai seems to be another example of this growing trend. “Master of Chinese Modernism” divided nearly half a century of work into seven sections. Before we rush to recount the achievements of a “master of modernism,” we should first ask the obvious question: Why has Zhang been overlooked? Solving this mystery may prove a more useful means of coming to grips with Zhang’s aesthetic vision.

Born in 1900, Zhang Guangyu began his career with an apprenticeship as a set painter at the Shanghai New Theatre under Zhang Yuguang. Zhang Yuguang served as headmaster of the Shanghai Chinese Art College, until a disagreement with Liu Haisu took place, influencing Zhang Guangyu to keep his distance from the three pillars of modern Chinese art: Liu Haisu, Xu Beihong, and Lin Fengmian. Zhang Guangyu established an aesthetic vision in the flourishing commercial environment of 1920s and 30s Shanghai that was slowly but surely repressed by the dramatically changed realities of the post-1949 era.

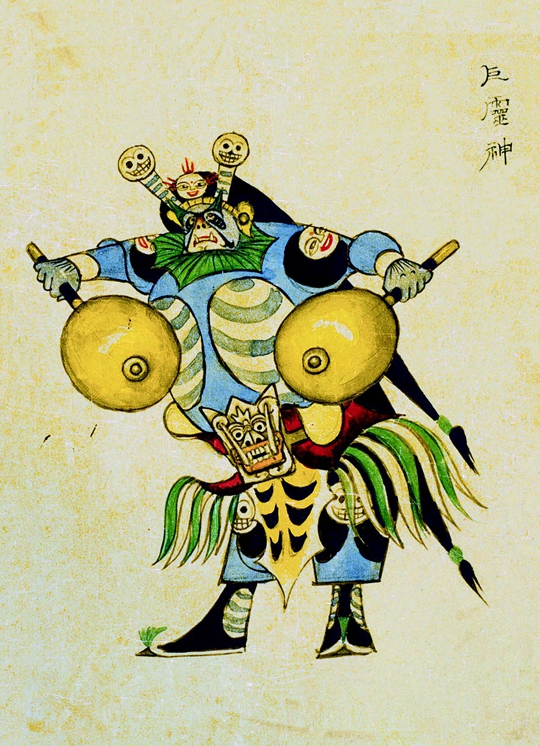

Although he eventually managed to find employment in the Department of Decorative Arts at the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, this hard-won academic position in a charged political environment proved a poor substitute for the fresh and lively cultural environment of the city, pregnant with modern ideals. It was at this point that Zhang’s fall from grace began. More pragmatically, the sheer range of his professional interests seemed to cause a lack of focus. Moving freely between media and publishing platforms, Zhang’s lack of a distinctive style saw him neglected by orthodox histories that recognized only four schools: Chinese painting, oil painting, woodcut, and sculpture. From the start of his career as an art editor at World Pictorial to his instruction at the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts in 1957, Zhang’s professional work was grounded in the graphic arts of commercial art and mass communication: cartoons, advertisements, satirical drawings, publishing, and book illustrations. Early Art Deco and other modern graphic design contributed to the formation of his decorative cartoon style, and to his later withdrawal into decorative arts research.

Zhang Guangyu’s early work is virtually inseparable from the urban culture of Shanghai in the 1920s and 30s, fully absorbed into the marketplace and linked to the international. Though he never studied abroad, Zhang’s work from the early 1930s incorporated elements from the European avant-garde. He spent seven years as an illustrator for British American Tobacco, where a well-stocked library and stable of artists from around the world provided an irreplaceable source of professional training.

The influence of Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, whose illustrations were frequently featured in The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, was particularly important to Zhang Guangyu’s work. Covarrubias was a close friend of prominent Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Zhang identified not only with Covarrubias’s and Rivera’s left-wing politics, but also with the unique way in which they married Mexican folk art traditions to high modernism. According to Ye Qianyu, Covarrubias inspired Zhang to become bolder with his use of exaggeration, allowing Zhang to develop an individual style as one of the top professional cartoonists in Shanghai. After the outbreak of World War II in 1937, Zhang devoted himself to topical satire, using eye-catching elements to provide an aesthetic response to contemporary issues.

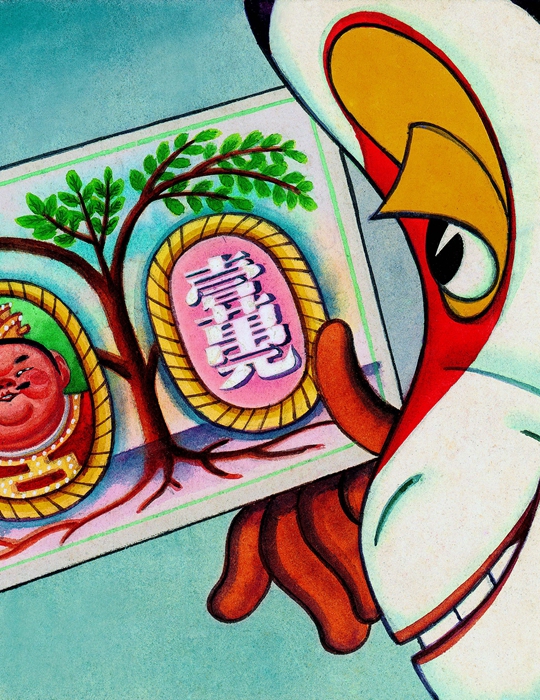

An important development occurred with his 1945 work, The Four Horsemen of the Mountains and Passes, in which Zhang Guangyu layered elements of mythology and wild creativity on top of his foundation in illustration. This process culminated in his next major work, Manhua Journey to the West, a grand poetic saga that informed the art design of the groundbreaking animated film Havoc in Heaven.

Zhang Guangyu was one of the most confident early Chinese artists to assimilate western modernism, but his approach was by no means systematic. Zhang’s modernism was inspired more by modern life and his education in the arts, facilitating a homegrown kind of thinking separate from the ideologies put forward by particular systems of aesthetics like Cubism or Surrealism. In this regard, he was not alone. As Michael Sullivan has written, many artists at the time suffered from “indigestion from conceptual overeating and the non-stop discovery of new styles. Free to pick up this or that style, they were almost completely unaware of how or why these approaches were adopted in the west.”(1)

Even so, their ignorance did not prevent these artists from advancing the cause of Chinese modernism. Zhang Guangyu’s decorative style formed a school all his own, one that influenced not only his peers but also the next generation of artists in cartoons, decorative arts, and industrial arts. Zhang, however, never had a clearly defined position comparable to Lin Fengmian’s liberal stance or Pang Xunqin’s Storm Society modernism. For all his strengths as a practicing artist, Zhang was not a system-builder.

After 1949, Zhang Guangyu’s creative network began to break down: first the commercial art market and publishing environment he had relied on withered away, then a new political environment made satirical cartoons impractical. In response, Zhang devoted himself to the academic study of the decorative arts, and worked on animated films. His research relied on the ups and downs of the politically troubled Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, while his animation depended on a group of older filmmakers at the Shanghai Animation Studio who were destroyed by the Cultural Revolution. Zhang died in 1965, before he could witness the disappearance of Chinese animation beneath a tide of Japanese and American imports in the 1980s, leaving him to be rediscovered by the art world some decades later.

Translated by Nick Stember