Time as Provocation: on “Wang Bing: Three Portraits”

| May 26, 2016 | Post In 2016年4月号

Courtesy Wang Bing

PHOTO: Johnna Arnold

For the increasingly urbanized Chinese population, web and mobile apps like Taobao expedite various social and monetary transactions, whether to schedule wakeup calls from fictitious boyfriends and girlfriends or seek a graphic designer for a company logo at 3:00 AM. It is against this social backdrop that we can come to understand the power in the uncompromising films of Wang Bing, the Beijing-based filmmaker who transacts in a very different kind of temporality, social reality, and political consciousness.

The “portraits” of the exhibition title refer to three of Wang Bing’s films, shown not as screenings with a beginning and an end but in the form of a gallery exhibition. These are trenchant confrontations of individual lives that have been forgotten in the grand narratives of contemporary China. Vine (or Miaopai, the Chinese answer to the video sharing app) playbacks these are not. With the 14-hour film Crude Oil (2008) as the centerpiece, curators Anthony Huberman and Jamie Stevens set up an exhibition that allows the frame of the institution to buckle. The Wattis Institute is open five to seven hours a day, and it will take three days of visits to complete this exhibition, taunting our habitual relationship to time into a provocation.

Courtesy Wang Bing

PHOTO: Johnna Arnold

Crude Oil takes up most of the exhibition space and is shown on a monumental screen viewable from two rows of cinema seats installed on a low platform. In this configuration, the durational act of viewing is subtly suggested, demarcating subjectivity as a stage in itself. We confront the habitat and the grueling 14-hour-long work day of crude oil field extractors in the Gobi Desert of Qinghai Province. Under these perilous working conditions, we are pushed to witness not only the act of labor itself, but also the interstices of boredom and breaks in between. What we see at first is a break room fashioned out of a metal shipping container, where workers banter, text on their mobile phones, and nap. Later, we watch the workers at their temporary home, another shipping container with windows along the ceiling that gives the sensation of being in the bottom of a well, as they watch television and eat. In between these scenes, the windy terrain of the desert casts a conflicted beauty in stark contrast to the lives of these workers. Day and night seem discombobulated. As in all his films, Wang Bing shoots on a digital camera with a minimal crew, and his camera never seems to shut off, and does not inhabit the space as either surveillance or agitprop. The history of film is indelibly connected to the documented lives of workers, as attested by one of the earliest moving images, the Lumière brothers’ 1895 film La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon). Fusing time and life, Wang’s film paradoxically elicits a sense of displacement and de-temporalization of the here and now, radiating a strangeness and discomfort as we watch other human beings engaged in the banality of their existence.

Courtesy Wang Bing

PHOTO: Johnna Arnold

Bracketing this magnum opus are two shorter films that were made a year prior to and a year after Crude Oil. In one the subject never utters a word, and in another the subject speaks throughout the entire film, thereby situating the viewer in a diametrical time-space where language is an unstable ground. In the front room is Man With No Name (2009, 94 min). It follows, for four seasons, a man who lives outside the structure of civilization in an underground cave in a remote part of northern China. Wang Bing came across the man while shooting his first feature-length fiction film, The Ditch (2010), and was moved by the basic ways in which he livec in opposition to material desires. He is without a name because, when Wang asked for permission to film, the man never responded, and it is this implicit intimacy that sustains the entire film. Agrarian and post-apocalyptic, the man seems to exist out of time, pointing to a past civilization and to an imagined future, a present as a kind of science fiction.

Courtesy Wang Bing

PHOTO: Johnna Arnold

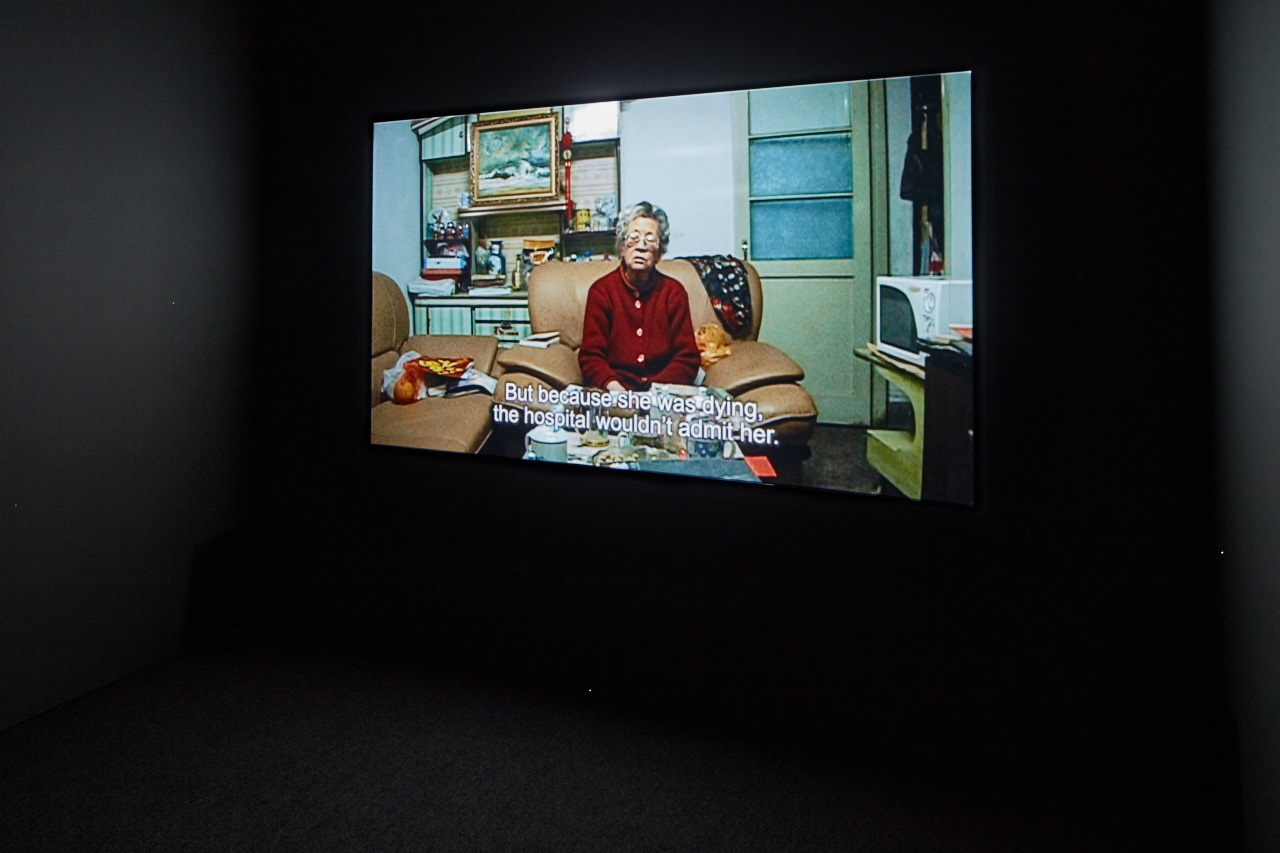

In the backroom is Fengming, a Chinese Memoir (2007, 227 min), in which the camera follows its subject, He Fengming, into her apartment, where she recounts, throughout the entire duration of the film, her life in post-1949 China. Both journalists committed to the Cultural Revolution, she and her husband were sent to reeducation camps. Her husband, Jinchao, was later sent to the brutal Jiabiangou camp in the Gobi Desert (thus rerouting us back to the locales of Crude Oil), where he died of hunger. The couple never reunited. In the early 1990s, He published a memoir titled 1957: How I Lived It. Deceptively straightforward, several temporalities run in tandem and in entanglement in this four-hour-long documentary: the filmic time, the historical time of the cultural upheaval, and the personal time of the subject. Wang Bing does not pose any questions to his subject, and bridges that distance through a committed lack of intrusion. She expresses, with a resolute clarity in chronological details, 30 years of her life, juxtaposing detail and sentiment. In the living room, against the setting sun, He slowly becomes obscured in darkness, not long after a potent passage in which she reminisces on her husband:

“I was his world, his heaven and his sun. And now suddenly this sun has disappeared.”

With this film, the oral tradition serves as a direct confrontation through which the testimonies from the past can be told in real time. It puts the body, the holder of subjectivity, back into a language that we so often hear and read about in abstraction en masse.

On a monitor in an adjoining room, a different film each day is selected by the artist Lucy Raven, providing, in her words, “entry points into thinking about matter, movement, space, and the stuff in Wang Bing’s work that gives complexity to still life.” The oldest of these, Hollis Frampton’s 1969 seven-minute short film Lemon, exemplifies this refraction of life through spatio-temporal means. A lemon is illuminated up close as the light source intensifies and diminishes, a sped-up version of the rising and setting sun. The film pulsates as if taking in each second as a moment of hesitation, until the fruit is completely concealed in shadow. It recalls one scene in which He Fengming, shrouded in darkness, suddenly addresses the filmmaker: “Would you mind turning the light on?” Only, in Wang Bing’s work, when the lights are on, the film is still running, complicit with time.

Kevin Jerome, Century, 2012

PHOTO: Johnna Arnold

In the waning glimmer of light on the surface of the fruit, I am reminded of the lunar landscape of the desert where the workers toil, and the traction of time in all of Wang Bing’s films, living breathing entities. If these films are demanding, it is not that they demand simply a viewer’s time, but that they reflect back to us a real necessity beyond what is depicted, beyond its geopolitics, and force us back to think deeply about our own civic lives, our ethics, and our engagements. It purports that the present moment, if we give it time, has real implications.