Wu Tsang A Life in Process

| May 19, 2016 | Post In 2016年4月号

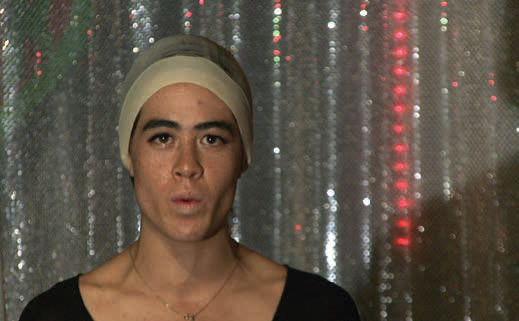

Courtesy Spring Workshop, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, and the artist

Filmmaker, artist, activist and organizer Wu Tsang describes herself as “multi-multi”(1)—a description she deploys in order to explain a position predicated on hybridity and contradiction. This approach to identity, and the refusal to be categorized in normative terms, has been somewhat of a constant in Tsang’s life. Born in Massachusetts, USA, in 1982 to a Chinese father (whose family fled Chongqing during the communist revolution) and a Swedish-American mother, she quickly became conscious of her unique cultural background—Eurasians were not all that common in New England back in the 1980s, after all. As a result, she began to (problematically to some) identify as “brown,” though Tsang has stated that this has nothing to do with the color of her skin but more to do with the condition of being marginalized.(2) In other words, an other by any other name would still be an other.

This hybridity was coupled with a burgeoning sense of gender fluidity (Tsang identifies as trans), which added to a sense of alienation that led to a fateful 2005 trip to China during which Tsang hoped to discover her cultural roots. Upon her arrival, however, she was faced with a devastating reality: even in China, she did not belong—a formative moment in which, as she recalls, “displacement becomes your sense of being.”(3) After that trip, Tsang moved to Los Angeles with an openness that came out of the loss she experienced in her ancestral homeland. It was here she found a sense of place in The Silver Platter, a bar in downtown LA for the city’s LGBQT community. She began organizing a night at the bar called Wildness with Nguzunguzu and DJ Total Freedom, which lasted from 2008 to 2010, and co-founded a free legal clinic next to the bar called Imprenta, which dealt with various concerns, from support for completing and filing immigration papers to free HIV testing.

Taking The Silver Platter as a microcosm, Wildness became Wildness—a 2012 feature-length documentary film (the artist’s first) that pays homage to a conflicted yet personal space by exploring “the struggle to find adequate labels / identities / descriptors” within a community where “differences were felt along lines of race, class, ethnicity, locality, [and] educational background.”(4) Wildness is a portrait of a site in which creativity and conflict collide and collude, where “two communities meld and implode at a … weekly party, thrown by the artists.”(5) Divisions in the documentary were made evident: Tsang did not describe the regular clientele as “queer,” pointing out that the parties they organized attracted a different scene to the bar’s regulars, who pre-dated the Wildness crowd, as she once noted, “by about 45 years.”(6)

Courtesy Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi and the artist

The experience was far from utopian. As the Wildness parties became more popular, Tsang and her collaborators began to wonder if they had compromised this safe space by exposing it to a wider public—an accusation that has been levelled at the artist not only by others, but also by herself. It was but another hard lesson. “The Silver Platter taught me about recognizing the limits of my own understanding of others,” she has said, “despite my well-intentioned critical education as an activist, artist, and queer person who identified with a lot of the struggles that my sisters at the bar faced.”(7)

These contradictions fed the form: “I tried to tell the story from a deeply personal perspective, because, needless to say, this film is riddled with complicated representational issues,” Tsang once mentioned.(8) But Tsang had, by then, long engaged with such contradictions, filming in 2009 (at The Silver Platter, in fact), a performance of a monologue written and performed by autism activist Amanda Baggs in the 2007 YouTube video In My Language. In the work, Tsang takes on Baggs’s call for a world in which different ways of being are accepted equally—in which true diversity is a political goal, and not a threat.

Courtesy Spring Workshop, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, and the artist

PHOTO: Ringo Tang

This is not a naïve politics. In Wildness, for instance, she wanted “to challenge the popular notion that ‘safe spaces’ are utopic and homogenous” while considering what it might mean to speak for, or represent, another person, or an entire community.(9) In an essay she wrote for the Whitney Biennial catalogue in 2012, she sums up the lesson she learned in making the film: that relation is difficult, and coming together can be a painful and difficult process that takes time and work. If such safe spaces are to function, she says, “they must be risky and contested, even dangerous. In a word: coalitional.” Of course, in the twenty-first century, forming a coalition—let alone maintaining one—is perhaps one of the hardest and most urgent challenges we face today. This is particularly true if you consider the march of technology, which has appeared to nurture in equal measure an increasing sense of isolation, alienation, and community. Fittingly, one of Wu’s more recent works, A Day in the Life of Bliss, presents an immersive film installation that acts as a proposal and a teaser for a developing feature film. The story is set in the near future, when humans are controlled by a “panoptical social media platform.” It follows the life of Bliss,a young performer navigating a brave, new world, played by performance artist boychild, who has become something of a firm collaborator.

Perhaps there is an element of autobiography embedded in Bliss’s character. Indeed, during her 2015 residencies at Spring Workshop in Hong Kong, boychild was a constant companion as Tsang developed her latest work based on her 2005 journey to China, which included a trip to a house-turned-museum in Shaoxing: a short film called Duilian, which premiered in March 2016 at Spring Workshop. The film explores the relationship between nineteenth-century revolutionary poet Qiu Jin (1875–1907) and her “calligrapher friend” and lover, Wu Zhiying (1867-1936), otherwise known as Madame Wu, after whom Tsang took her name when she changed it years ago.

Courtesy Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi and the artist

PHOTO: Michael C. W. Chiu

Tsang calls Duilian “a transformative love story between two people,” since Qiu Jin, married with kids, was completely changed after meeting Madame Wu. “The relationship sparked a new life inside of her.”(10) When Qiu Jin became a revolutionary, a crucial, underlying theme opened up: “a tension between one’s love for an individual versus one’s love for a cause, or a movement, or nation.” Tsang takes a firm stance on how the love story is framed: “I think ‘lesbian’ is such a limited word whose use becomes very complicated… in the context of Asia and specifically China or Hong Kong, where LGBT language can be considered very westernized, especially when there are all these other ways that people experience their sexuality, which can be expressed or codified in ways that are permissible but unspoken.” What was more interesting for Tsang was the challenge of representing this historical relationship outside of language “by letting it just be.”

Courtesy Spring Workshop and the artist

PHOTO: MC

With each gaze that views Duilian, a chain reaction occurs that speaks to the original reasons as to why Tsang chose cinema over visual arts in the first place. Accessibility was always her priority, and cinema allows for both mass distribution, and the representation of greater complexities without the problematic crux of language. Tsang views filmmaking as a mode of organizing—“not only because you bring so many people together for production and collaboration, but because you create a mise-en-scène in the film that documents a living community.” For Wu, “community” only exists “through representation”—a “transportable world / dialogue / space” with “the potential to generate other communities, as it becomes absorbed by different audiences over time.”(11)

HD video, color, sound, 5 min 15 sec

Courtesy Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Clifton Benevento, and the artist

According to her estimation, Tsang now works half in film and half in installation, which she views as an immersive way of experiencing film. Valuing both disciplines equally, she recently explained: “Film brings a lot of narrative into my visual art, but my visual art enables me to think things through in a way that cinema doesn’t allow for, such as complexity and ambiguity, or ways of looking that are much slower or more contemplative.” Even here, Tsang does not maintain a position that is neither one nor another, nor in between, but in a state of constant mediation. This relates to how Tsang has made a practice out of evading—or challenging—the question of who she is, and, by association, who we are, by turning the question into a process.

——————–

(1)Wu Tsang and Cathy Rifkin in conversation with BYOD at SXSW, 2012.

(2)Ming Lin, “Wu Tsang: Invisible Boundaries,” ArtAsiaPacific, May/ June 2014, pp. 84–88.

(3)See 1.

(4)A conversation between Wu Tsang and Andrew Berardini for Vdrome.

(5)Eric A. Stanley, Wu Tsang, Chris Vargas, “Queer love economies: Making trans/feminist film in precarious times,” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, May 2013, online.

(6)See 4.

(7)See 4.

(8)See 5.

(9)See 4.

(10)In conversation with the author, March 2016. All subsequent quotes taken from this discussion.

(11) See 5.