Sascha Braunig : The Hollow Body

| June 3, 2016 | Post In 2016年4月号

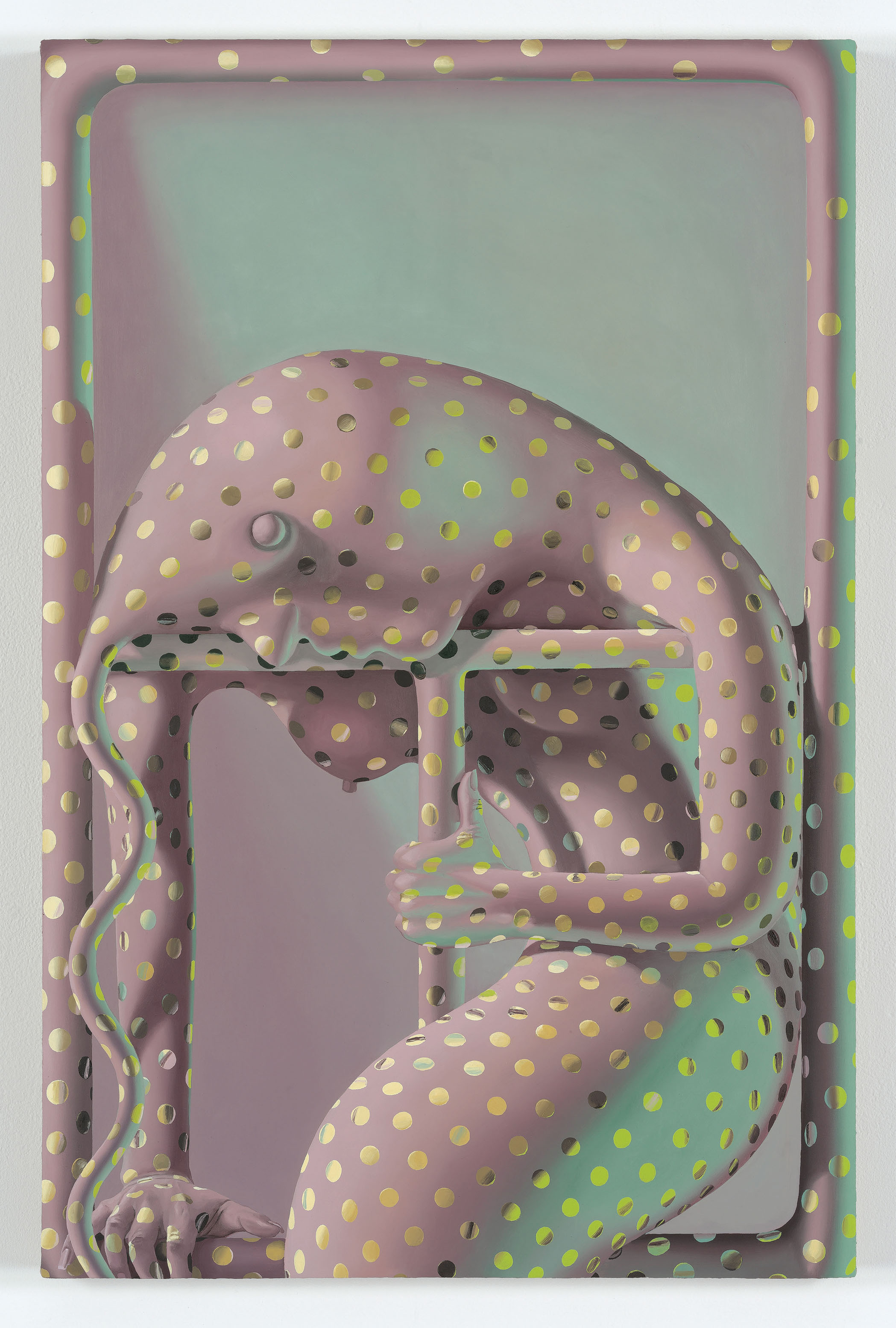

Courtesy Foxy Production and the artist

To encounter the paintings of Sascha Braunig is to be confronted with an unsettling, hypnotic world. She creates portraits of figures dissolving within their own borders, moving in and out of corporeality and bending the laws of reality. In her technically brilliant paintings, studio portraiture merges with science fiction, and patterns merge into the skin of humanoid beings that seem to be either swallowed up by or born out of digital networks. Yet, despite all their otherworldly energy, her creations are strangely lifelike. They are at once realistic and members of a fantastical universe. They could be a species of futuristic beings, or perhaps a reflection of the mindscapes of our increasingly disembodied, modern lives. Critic Roberta Smith has called Braunig “an inspired reanimator of Surrealism,” and she is among the wave of leading young painters in the United States reenergizing the medium.

I visit Braunig in her studio on a freezing morning in January. She is based in Portland, Maine, a tiny American city located a two-hour drive north of Boston. It’s far from the influence of New York’s art world. Yet, because of the lower rents that have historically drawn artists here, the remote location has allowed Braunig an abundance of time and space to nail down her utterly distinctive style. Her studio lies in a building downtown that also houses SPACE Gallery, the city’s leading independent art space.

A series of half-finished oil paintings lines the walls. These will be shown in a solo exhibition at the Kunsthall Stavanger in Norway this spring. Her figures are growing, now taking up the entire canvas, and the patterned backgrounds have been completely engulfed by the body. The paintings are almost sculptural in their compositions, pulling your eye deep into the folds of the female form. Braunig calls them “a simple expansion” from the smaller portraits that drew critical acclaim at the New Museum Triennial, “Surround Audience,” in 2015.

It’s been a quick rise to prominence for this young artist. Braunig was born in 1983 on the west coast of Canada. She studied for her BFA at Cooper Union in New York, followed by an MFA in the painting department of Yale University. The genius of her style can be traced to those years at Yale, where she began to experiment with video—stepping away from the formalism of painting and creating masks and props for cunning, surprising video works like My Other Sexy Look and Ex Salon (both 2008). When she returned to painting, the props came with her.

Braunig moved to Portland in 2010 and set about creating mannequin heads and covering them with paint, fabric, and sequins. She would carefully light these entities, capturing their physical realities like a traditional still-life painter. Paintings like Untitled (Icy Spicy) (2011) emerged: a cunning play on historical portraiture where the figure’s patterned skin merges into the background. It’s what Braunig calls “hyper-illusionism.” “It’s going through my mind rather than a computer,” she says of her process. “It’s interesting; people think the paintings look so digital, when they’re made in this very crude and analogue way. But I’m interested in that interpretation.”

While she was creating works for the New Museum Triennial in 2015, she found herself contemplating “cultural phenomena, this internet that we’re so embedded in, and how that could be represented.” She was interested in “figures dematerializing into the background, so it’s unclear where the figure ends and where the environment or network begins. It’s sort of a hollowed-out subject. This hollow body I’ve seen in fashion too, it seems to be the zeitgeist.”

Courtesy Foxy Production and the artist

This sense of the dispersing self, the lack of a fixed existence of her fictional beings appears again and again. In Squirm, a head seems to be either liquefying into its background or manifesting out of the very fabric of the universe. In Chur (2014), a brain-like organic form is set against a background of the same matter, swirls spiraling out from the neck. It’s a startling vision, bringing to mind the gulf that exists between the physical realities of our bodies and our online, virtual selves: the contradiction between the permanence of our sense of self that we hold in our minds, with the reality of our ever-changing, organic bodies. Elsewhere, like Hilt (2015), figures are literally climbing out of their frames.

“As a painter, you are always working within this boundary,” she says of her impulse to challenge the frame within her paintings. “I guess it’s quite a modernist idea really; it seems sort of cruel to be putting figures in this box—so I am trying to give them a little bit more power or aggression towards this frame that they’re so bounded by.” As we discuss her newest works, she says she is drawing on her own identity as a female artist. She has been looking back at art history and contemplating her place within its story. “I’m always thinking about this extreme, exhausting history. In a way, I am reproducing or continuing it but I’m trying to inhabit it as a female and interpret that history through me.”

Her influences are far-reaching, from seventeenth-century Dutch painting to the peripheries of surrealism. One of her newest paintings is inspired by the ancient Roman sculptural form of herna, strange, column-like sculptures in which a head appears atop a pillar with male genitals protruding lower down on the rectangular column. She has appropriated this form in paint and created an exquisitely abstracted version; flowing curves suggest a woman’s hips with a stunningly realistic, flower-like object painted in the space between the legs.

She tells me about a recent trip she took down to the Harvard art museums in Boston, where she saw Francois Boucher’s painting Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour (1750). She was thinking about Poisson—the official chief mistress of Louis XV and an immensely powerful member of the French court—and how she collaborated with Boucher in creating her own representation.

“Apparently she herself was an artist, a printmaker,” says Braunig. “She worked with a portraitist to work on her own brand. So there is all sorts of coded imagery within that portrait. I think about these stories,” she adds. “I’m interested in female historical figures who break the mold in some way, or help to construct their own public face.”